Physician models of feet help people with diabetes understand the impact of the disease on blood flow to their lower limbs. (Megan Wood, inewsource)

By Cheryl Clark, inewsource

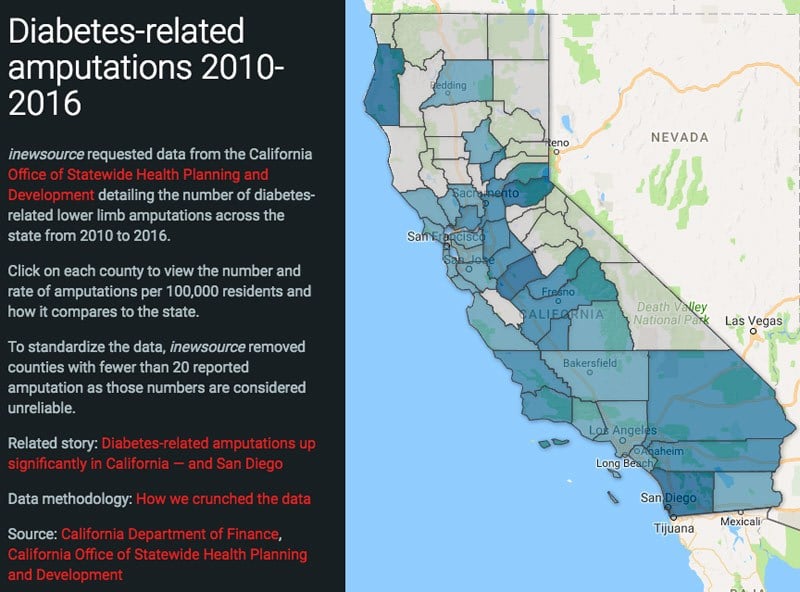

Clinicians are amputating more toes, legs, ankles and feet of patients with diabetes in California - and San Diego County in particular - in a "shocking" trend that has mystified diabetes experts here and across the country.

Statewide, lower-limb amputations increased by more than 31 percent from 2010 to 2016 when adjusted for population change. In San Diego County, the increase was more than twice that: 66.4 percent.

Losing a foot, ankle or especially a leg robs patients of their independence, hampers their ability to walk and makes them more vulnerable to infection. It also can shorten their lives.

This trend, which inewsource documented with state hospital data, is one physicians, surgeons and public health officials are at a loss to explain, though many have theories.

Edward Gregg of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said the California numbers are worrisome.

Public health officials consider amputations to be an important indicator of a region's diabetes care because diabetes and its complications can be prevented, said Gregg, chief of epidemiology and statistics for the CDC's Division of Diabetes Translation.

"If we see it going down, then it's a good sign, because so many aspects of good diabetes care are in theory affected. And when you see it going up, that's a concern," he said.

The CDC has noticed an increase of 27 percent nationally in the rate of amputations among people with diabetes between 2009 and 2014. Previously, the numbers had been declining.

Gregg suggested one cause for the increase could be that the country's population is aging - advancing age is a risk factor for diabetes - and that more people are being diagnosed with diabetes.

The increase also could be attributed to inadequate attention to diagnosing and managing the disease in some populations, he said, adding that in some populations, there may be less attention to diagnosing and managing the disease.

But those reasons together don't explain the stark increase in such a short period of time, he said.

Why are amputations a risk for people with diabetes?

Diabetes impedes blood circulation, which impairs the body's ability to heal and makes extremities vulnerable to nerve damage. That means patients might not feel the pain of injuries or blisters, or notice when they get infected.Clinicians often use techniques to repair wounds and preserve limbs, in hope that amputations are a rare and last resort to prevent infection spread.

Father Joe's mistake

The medical saga of Father Joe Carroll helps illustrate the problem. Over many years, the Catholic priest and creator of Father Joe's Villages, a San Diego network of services for the homeless, didn't do a good job managing his diabetes.

"I was a bad patient," he said.

Gradually, his diabetes curtailed oxygen flow, first to one of his toes, then to his feet and to the lower parts of both legs, leaving them vulnerable to nerve damage, injury and infection.

So one by one, they had to be removed in a series of surgeries to stop the spread.

Now 76, the man who goes by Father Joe said he regrets he didn't work harder to prevent his diabetes from progressing.

"I refused to go on a strict diabetes diet," he said. He liked bread, macaroni, sugar and starch. "We aren't supposed to eat potatoes," he said. "I'm Irish. I live on potatoes."

Father Joe said he's speaking out about his health issues in the hope it will make "at least one person" among the growing number of people with diabetes "change their approach and save themselves." He knows, as research has shown, that amputations will probably cut his life short.

Diabetes experts mystified

The California Department of Public Health said in a one-sentence email it "does not have information" on why diabetes-related amputations have increased.

Many diabetes experts, foot specialists and surgeons were puzzled by the trend. They offered multiple explanations for what might be behind the shift from a decrease in amputations before 2009 to an increase beginning in 2010.

Some clinicians said hospitals might be increasingly diligent about adding a diabetes diagnosis to a billing code, which can increase their reimbursement, although that did not appear to be a factor in the California data during the seven-year period inewsource analyzed.

In addition to the aging population, clinicians may be moving faster to surgically remove a limb if it looks like specialized wound treatments won't work. Several foot and ankle specialists said podiatrists and vascular surgeons may be doing more amputations on the same patient over time, taking off one toe per hospital admission instead of two or three, in hope that preventive care will avoid further surgeries.

Expanded health coverage with the Affordable Care Act might have brought more people with diabetic foot ulcers into a doctor's office starting in 2014. But that doesn't explain the increase from 2010 to 2013, before the ACA took effect.

Linda Geiss, director of the CDC's diabetes surveillance section, speculated some of the increase may be the aftermath of the Great Recession of 2008, when people with diabetes lost jobs and perhaps delayed getting needed medical care.

"Maybe they weren't taking the medications like they should because they couldn't afford it," Geiss said.

Jonathan Labovitz, a Pomona foot and ankle surgeon and podiatry researcher affiliated with the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, said some of the blame likely can be traced to 2009 when the state stopped paying for outpatient podiatry services for patients under Medi-Cal, California's health program for the poor.

State health officials confirmed that Medi-Cal excluded podiatry services as of July 1, 2009 because of the state's budget shortfall, but said podiatry services are covered when provided by primary care physicians, federally qualified health centers, rural health centers and tribal clinics, and are covered by some Medi-Cal managed care plans. State officials declined to comment on whether the change resulted in an increase in amputations.

Dr. Caesar Anderson, UCSD diabetes wound specialist, said he was "shocked" by the precipitous rise in amputations, and assigned blame to emergency room personnel and surgeons rushing to amputate "even when the wound is not that alarming."

He said he's seen this repeatedly, among orthopedic and other surgeons who want to sever limbs quickly, and he's heard stories from patients that they were given no options.

Anderson blamed a "culture of frustration" among clinicians who say to the patient "you'll never get better; we'll probably just save you the headache and just amputate...and we have some fantastic prostheses we can get you into ... let's just get it over with."

Kaiser and Scripps Mercy higher volume

In raw numbers, 1,047 amputations occurred within hospitals in 2016 among patients who listed a San Diego County address. The data showed a steady increase from 591 in 2010 or 77 percent.

At San Diego County hospitals, 1,142 patients were discharged after a lower-limb diabetes-related amputation in 2016, up from 651 in 2010. Those figures include patients who might not live in the county.

Kaiser Foundation Hospital Zion in San Diego, which had the second highest number of diabetes-related amputations of any hospital in the state in 2016, saw a 95.2 percent increase since 2010.

Kaiser spokeswoman Jennifer Dailard attributed the increase to several factors: a much greater percentage of enrollees diagnosed with diabetes, many more members who are 65 and older and to growth in membership between 2010 and 2016.

Kaiser's membership increased about 20 percent, from 500,000 to more than 606,000 from 2010 to 2016, but the number of enrollees with diabetes who actually were admitted to a Kaiser hospital dropped from 6,084 to 5,064 during this period, according to the state's data.

Dailard said the increase is largely in more minor amputations of the toe or foot "due to a more aggressive approach to minor amputations to avoid major amputations in the future." Nationally, Kaiser amputations have decreased, she said, adding that the San Diego Kaiser system is "committed to bringing these results to San Diego."

Scripps Mercy Hospital, which had the fourth highest number of diabetes-related amputations among California hospitals, saw an 80 percent increase over the seven-year period, from 109 in 2010 to 196 in 2016.

The failure of people with diabetes to attend diabetes education programs might be a major contributing factor to the increase in amputations, said Dr. Athena Philis-Tsimikas, an endocrinologist and diabetes researcher at Scripps Memorial Hospital in La Jolla.

Philis-Tsimikas suggested that patients in Chula Vista, served by Scripps Mercy Hospital in that city, may be driving some of the increase, in part because of its greater population of Latinos, who have a higher rates of diabetes. Scripps Mercy in general also has a higher number of Vietnamese and Filipino patients, who also have a higher risk for diabetes, she said.

A Scripps spokesman would not elaborate beyond Philis-Tsimikas' remarks.

Good amputations?

Several diabetes specialists and public health officials suggested the increase in amputations could be a good thing, a sign that persistent diabetes-related wounds and infections are more frequently being addressed rather than allowed to fester. Maybe more patients lives are being saved.

Dr. Philip Goodney, a vascular surgeon and limb amputation researcher with the Dartmouth Institute, which analyzes Medicare data to see health trends, said it's hard to know what California's data means without more complicated analysis.

But it could be "more a marker of success than failure," Goodney said. Amputations of toes or feet might avoid more drastic amputations of an ankle or leg, he said.

Philis-Tsimikas of Scripps also urged caution. "I'd be careful to say the reason is a bad reason until you know what might be driving that increase," said Philis-Tsimikas.

The CDC's Gregg, however, was doubtful. "It's hard to buy the argument that an increase (in amputations) is good," he said.

The state data indicate that amputations of toes are increasing, presumably to keep infection from spreading to the foot, ankle or leg. But amputations of ankles and feet as well as legs increased statewide.

Dr. Benjamin Cullen, a foot and ankle surgeon with Scripps Mercy Hospital,

was unaware of the increase in amputations. He noted that more patients live with diabetes for longer periods of time and many wait to the last minute to seek care in the emergency room.

"With diabetes, patients have neuropathy, so they can't feel (sensations or pain in) their foot," Cullen said. "They get a wound, don't know it's there, the wound gets infected and they don't realize it. The first sign that they have is a foul odor coming from their foot, or a family member notices drainage."

Often, the infection has gotten into the bone, he said, leaving "no choice but to go ahead with the amputation" to try to save other parts of the limb.

The state's data underscored Cullen's point: At least in San Diego County, more than 76 percent of the patients who received an amputation entered the hospital through the emergency room, perhaps indicating that the need to grapple with an infected wound was delayed until it became acute.

Cullen and others noted that after patients with diabetes-related infections or other wounds are seen by a doctor or at a hospital, surgeons often perform surgeries to open arteries and restore circulation so that healing can begin. The process is called revascularization.

Then, patients are often referred to wound clinics and given prevention instructions going forward.

Those strategies don't work for everyone, said podiatrist James Longobardi, who specializes in diabetes-related foot and toe surgeries and wound care. He also is chief of surgery at Scripps Mercy Hospital in Chula Vista.

Dr. James Longobardi, foot and ankle podiatrist at Scripps Mercy Hospital Chula Vista. Sept. 12, 2017. (Megan Wood, inewsource)

His practice is dedicated to keeping patients from losing more limbs than they have to, he said.

But, he said, many of his patients - for a variety of cultural and other reasons, "can't grasp the seriousness of the situation, and it's very, very frustrating to many of our clinicians."

Dr. Misty Humphries, a vascular surgeon and diabetes-related amputation researcher at the University of California Davis, said she believes a big part of the problem is how common diabetes has become, so people don't take it seriously and don't proactively try to manage it.

"They become passive observers of their care," she said. People think they "can just take a pill ... and you don't really have to change your diet."

For Father Joe, the toll of diabetes continues.

He's lost sight in one eye because of diabetic retinopathy and is losing sight in the other. The wound on the end of what remains of his left leg refuses to heal, requiring weekly trips to Scripps Mercy for treatments. And, because he needs his shoulder muscles to move around, he has injured his rotator cuff, and that too will require orthopedic surgery scheduled this week.

Sometimes, he still feels pain in the ankles he no longer has, a phenomenon called phantom pain.

"It's the diet, which I ignored," Father Joe said. "The medicine can delay it, but it can't stop it. You have to stop the cause of it, which is all the sugar that you're getting."

Now, he said, he's paying the price. "I was dumb not to have listened all these years."

inewsource reporter Brandon Quester contributed data analysis to this report.

********

********

inewsource is an independent, investigative journalism nonprofit supported by foundations, philanthropists and viewers like you.

********

Read additional stories on the inewsource.org website.