SAN DIEGO COUNTY, Calif. — Tom Hom shuffled up four steps to the porch of an old house in North Park and knocked.

Knock, knock.

It was not just any old house.

Knock, knock, knock.

It was his old house. He was knocking on the same door he opened countless times when he, his mother, and his 11 brothers and sisters (and, eventually, his newlywed wife) all lived there. Almost 75 years ago.

Knock, knock, knock, knock.

The door did not open. Nothing stirred inside. A breeze rustled the trees on the patio.

Hom had made a day trip from Chula Vista, where he lives now, to meet the person or people living in the house and give them his memoir. If he met them, he would tell them: “Here’s the book I wrote about this house. My family lived here for 35 years.”

If he was sad the door didn’t open, he didn’t show it. “I feel we’re very fortunate to have spent all those days at this house,” he said. The family prospered there. They had good neighbors, he said.

For a Chinese American family like the Homs, trying to buy a house in a segregated neighborhood, having good neighbors wasn’t just a perk. It was crucial.

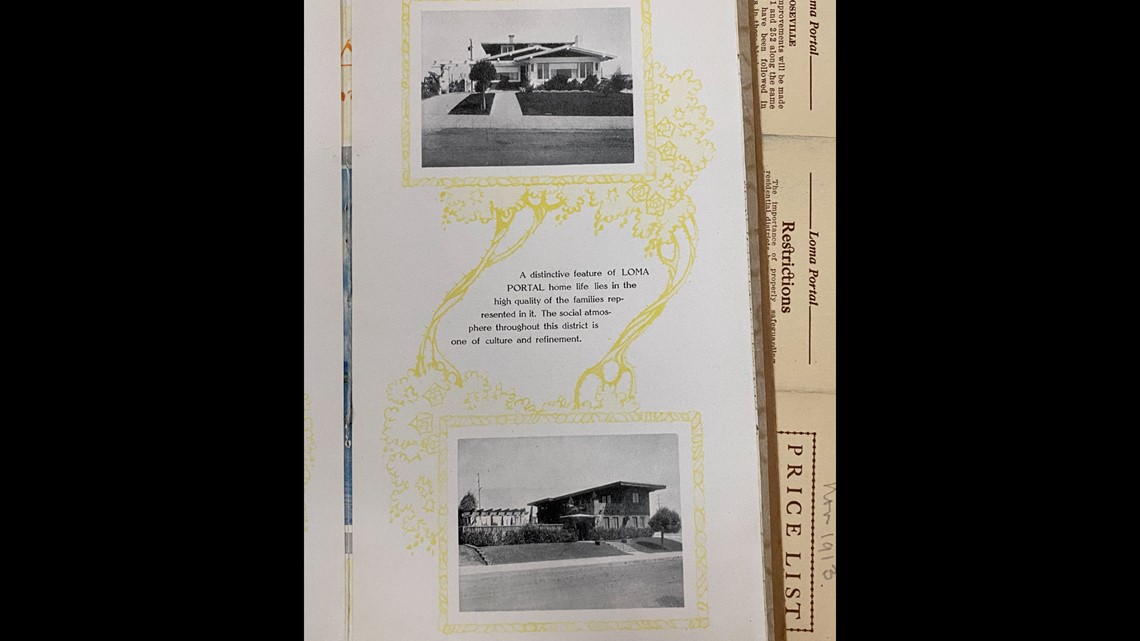

Like other San Diego neighborhoods, North Park in those days had many homes and subdivisions with racial restrictions, also known as covenants, designed to keep non-white buyers or renters out.

Hom said he doesn’t know for sure if his deed had such a covenant, but when their real estate agent first found the property, he warned them they might be blocked from buying it. They had already steered clear of other neighborhoods where covenants were common.

This time, instead of retreating, his mother pushed back — with a combination of charm and chutzpah.

That same year, a World War II veteran named Leon Williams was shopping for a home in Golden Hill. The house he wanted had a covenant. Williams is Black. He didn’t let that stop him from purchasing the property anyway.

Their stories show that in exceptional cases, families who weren’t white could move into segregated neighborhoods. But they were fully aware that in the vast majority of cases, in cities and neighborhoods across the county, from just north of the U.S.-Mexico border and all the way to Vista, such deed language prevented non-white people from doing the same.

When racism was trendy

Racial covenants proliferated across the U.S. in the first half of the twentieth century, marketed as a way to safeguard the investments of white buyers. San Diego, growing in surface area and population at a fast clip in those decades, was no different.

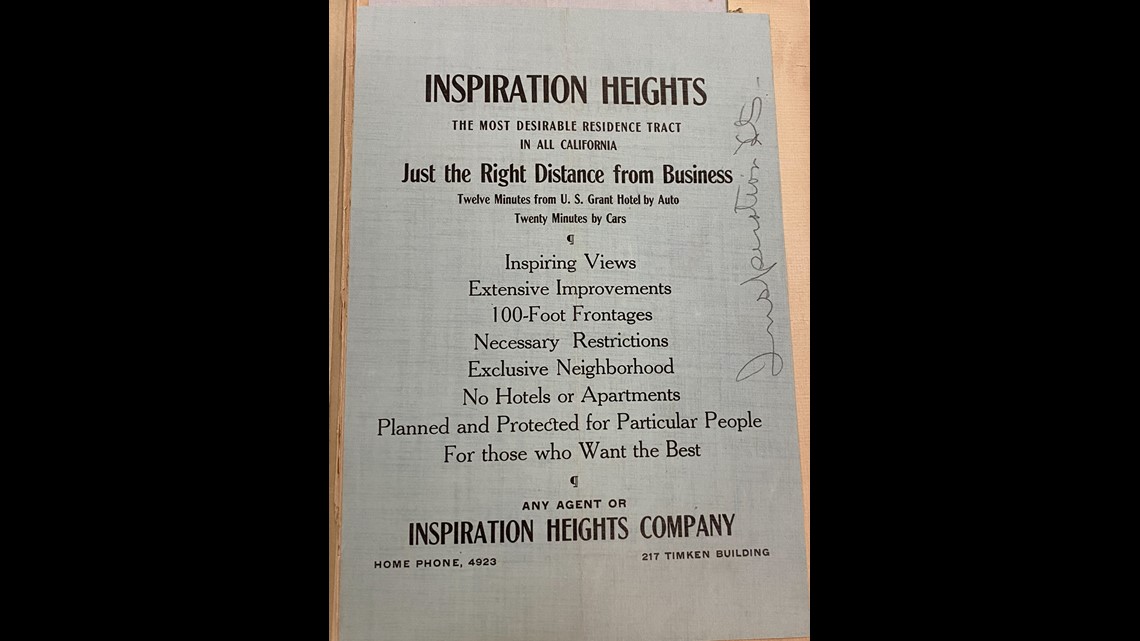

An undated brochure from around 1910 promised potential home buyers that Inspiration Heights, today part of Mission Hills, would be “forever protected from undesirable encroachments.” Conditions explicitly stated in the deeds protect “against all danger of deterioration because of the too near approach of any discordant element.”

Discordant: incongruous, out of place.

The clauses themselves often looked something like this:

"No conveyance, transfer or lease of said property, nor any lease of any building that may be placed thereon, shall be made to any person not belonging to the Caucasian race or being one of that race, and neither the said property nor any building thereon shall be used or occupied by any person not belonging to the Caucasian race, as owner, lessee or tenant, nor in any other capacity except as servant."

Sometimes, the language was even more pointed: In Imperial Beach, one seller repeatedly singled out Black buyers. Other restrictions targeted Chinese, Japanese, Ethiopian, Hindu, Jewish, Polish and other groups.

This kind of segregation operated on two levels, said Mary Jo Wiggins, a professor at the University of San Diego School of Law and an expert in housing discrimination: restrictive housing covenants forbade, under the law, certain kinds of people from buying certain properties. But it was also a norm: there were plenty of “non-legal ways to get to the same result.”

She added: "Real estate agents and neighbors could simply mention that such a covenant existed and this signal alone would often chill interest among buyers of color. Moreover, lawsuits attempting to strike down racially restrictive covenants were rare until the advent of the civil rights movement.”

Covenants were used in all sorts of neighborhoods.

“It really ran the gamut from very wealthy areas to middle-class areas,” said Wiggins, the law professor. “And the primary determinant was: could the neighbors come together, draft a contract and see that that contract went into the deed.”

Wiggins said understanding this history matters today. “Knowledge and the understanding of sensitivity to these issues can make us better at committing ourselves to eradicating new forms of discrimination that pop up from time to time,” she said. “In American society, because we are a pluralistic society, because we welcome many people from many places and we’re a fairly open society, it feels like there’s always the new outsider.”

Today racial covenants are not enforceable, but many old deeds still have them. There's no way to know how many remain on the books without a review of thousands upon thousands of records, but a new state law, Assembly Bill 1466, passed in September, aims to make it easier to uncover and erase racist language from deeds.

Inewsource partnered with National Public Radio and several of its member stations to determine the scope of racial covenant language in counties nationwide. The NPR investigation found racial covenants still on the books in all 50 states.

It’s impossible to know how many people were impacted by these clauses in San Diego, because deeds don’t include racial or demographic data about buyers or sellers.

But an inewsource review of digitized county records found more than 10,000 recorded property documents with race restrictions. Each of these represents a property removed from the pool of options available to non-white buyers.

“They were terribly pervasive,” Ron Buckley, a retired senior planner with the city of San Diego, said of the covenants.

“When you start to envision what the scope of things are and the application of the covenants, you start thinking, where the hell are these people living? How are they getting to work without getting up at four in the morning?” he said.

As Buckley spoke about this history, sitting on the shaded porch of his University Heights home, he brought up the restriction on his own house. His more than 100-year-old Craftsman bungalow has one, he said.

“I was interested,” Buckley said. “I looked it up and sure enough, it’s here.”

inewsource was not able to independently confirm the existence of a covenant on his property but found many others in University Heights.

Andrew Wiese, a professor of history at San Diego State University, said covenants caught on as people saw others using them. He likened them to certain architectural styles or features — only this time, it was “a fashion for white supremacy.”

Besides sub-dividers and sellers adding restrictions when a property went on the market, another method was through documents, also recorded with the county, called “declarations of restrictions” or “agreements for racial restrictions,” which could close off entire subdivisions to non-Caucasian buyers and residents. In many cases, the homeowners themselves banded together to do that.

Neighborhoods with widespread restrictions included parts of La Jolla Shores, Point Loma near Shelter Island, a swath of Rolando, and subdivisions in Solana Beach, Pacific Beach and North Park.

With each such document, large clusters of properties were plucked from the housing market for non-white buyers, leading those buyers to compete for a smaller pool of properties in less sought after neighborhoods or to turn to rentals.

Rafael Bautista, the co-director of the San Diego Tenants Union and a real estate agent and mortgage broker, put the practice of racial covenants in a broader historical context, where people of color have long been affected by “laws that limit land ownership, limit any type of wealth accumulation, any type of transference of wealth through generations.”

He continued: “If we’ve been deprived for 400, 500 years after they took our land from owning land, there’s going to be severe repercussions in how people are valued, how people are looked at, how people are respected and given their dignity. That’s all interconnected, because this all comes from this white supremacist ideology, this legacy of imperialism,” Bautista said.

In 1948 the Supreme Court ruled in Shelley v. Kraemer that racially restrictive covenants are not enforceable. Such covenants clash with the 14th Amendment, which calls for all citizens to be treated equally under the law, the court ruled. Racial covenants, in short, were recognized as a form of unequal treatment.

That ruling reflected and also foresaw a changing culture. As time passed, said Wiggins, sellers either decided that they wanted to put profit over bigotry so they could sell to the highest bidder regardless of race, or they actually decided that excluding certain people was not morally right.

Spotlight on San Diego’s covenants

An inewsource review of San Diego County records found more than 10,000 real estate documents with racial restrictions, starting in 1931, spread across the county.

This doesn’t account for the many restrictions enacted in the decades before, because the searchable and digitized records reviewed only go back to 1931, long after these covenants became common. (Older deeds aren’t searchable digitally. Classifieds, brochures and newspaper ads, though, also show restrictions as early as 1910, and older examples may also exist.)

There's no way to know how many covenants there were in all, over the decades, or how many remain on the books, without a manual review of hundreds of thousands of documents. Here is what a sample of more than 430 records with restrictive covenants found in around 120 subdivisions did show:

Covenants existed across the county, from Imperial Beach to Crown Point to Vista.

Covenants were intended to protect the wealth of white developers and homeowners, and they may have succeeded at that, but they ultimately failed at creating a permanently segregated San Diego. While some neighborhoods where covenants were common, such as La Jolla and Mission Hills, continue to be predominantly white and affluent, other areas where developers once wanted to keep out non-white people, including City Heights, Valencia Park, North Park, Paradise Hills, National City and Spring Valley, are now racially diverse.

Despite their prevalence, many properties were open to all buyers. Though only about 430 records after 1930 were examined in detail, the collection of deeds from the same time period contains many more examples of sellers who did not attach restrictions, or who imposed restrictions not related to race or ethnicity (and were instead related to building requirements and zoning).

Each covenant could speak for a single or multiple lots, or many acres of land. One transaction in Vista, for example, covered 200 acres. Discrimination didn’t just impact the living: in National City such language involved a cemetery plot.

Starting in 1931 and through the late 1940s, the frequency of racially restrictive clauses gradually tapered. There was one exception: the number dipped during World War II and rebounded as the post-war economy picked up.

Covenants started being canceled soon after the Supreme Court ruled they are unenforceable in 1948. A 1950 agreement for a National City property, for example, reads that the racial restriction is “cancelled and made no further force of effect on said property.”

But they also continued to be added, long after 1948. The most recent one found was from the late 1960s, for property in or near Julian.

Wiggins, the University of San Diego law professor, said changes in laws helped curb the practice.

“In modern subdivisions developed after about the mid-70s and onward, you don’t find as much evidence of this because by that time there was a revolution in civil rights law, in the Fair Housing Act, that made these kinds of formal mechanisms widely known to be illegal,” she said.

Beyond the searchable records from 1931 onward, a review of 77 grant deeds of properties sold over approximately two months in 1913 found four racial covenants.

Homes with no racial covenants, but often with other restrictions dealing with alcohol production or sales and minimum building requirements, were found in University Heights, Cardiff, Encanto and South Park. A property in San Ysidro had a racial covenant. City Heights had homes with and without covenants.

In the larger sample, grantors, or sellers, on deeds with racial restrictions include the Union Trust Company of San Diego; Bank of Italy National Trust and Savings Association and Bank of America National Trust and Savings Association (both became Bank of America); the La Mesa, Lemon Grove and Spring Valley Irrigation District, which became the Helix Water District; the San Dieguito Irrigation District; the Santa Fe Irrigation District; and Ed Fletcher, the produce salesman turned real estate developer and politician who had a broad impact across the region, helping develop Mission Bay and deliver water to San Diego, among other contributions, and ultimately lending his name to several places in San Diego County.

Theodore Strathman, the co-editor of The Journal of San Diego History and an expert on the history of water use in San Diego, said banks might have been grantors in the case of mortgage defaults or foreclosures. Districts might have bought land for pipelines or pumping and then decided it wasn’t needed.

Spokesmen for Bank of America and the Helix Water District declined to comment.

Catherine Blakespear, the mayor of Encinitas and a board member of the Santa Fe Irrigation District and the San Dieguito Water District, sent a link to an op-ed she wrote in August about covenants, the city’s history and its future. In that opinion piece, she commented, “For me, seeing these obsolete racial covenant deeds in my hometown reinforces the need for intentional actions and approaches to create a city that is diverse, desegregated and committed to equity.” She also responded to an invitation to comment, with an email:

“Some people were able to put down roots here and others were excluded. We need to consciously and intentionally open our high-opportunity community to more diversity. We founded an ‘Equity Committee’ in the city to work on this.”

Al Lau, the general manager of the Santa Fe Irrigation District, wrote in an email: “As an almost 100-year agency, SFID is dedicated to diversity and inclusion in all of our business practices to provide safe and reliable water supply for our customers. We emphatically do not condone any policy or practice that would restrict the basic human rights of any member of our community.”

In a phone call, Ron Fletcher, a descendant of Ed Fletcher, emphasized Fletcher’s many contributions to San Diego and suggested that his legacy should be judged in light of those contributions.

“I think there’s other things to focus on,” he added. “For you to bring something up from 100 years ago is kind of silly.”

Breaking through.

A few months before the Supreme Court ruled in Shelley v. Kraemer that this kind of discrimination is unconstitutional, buyers who weren’t white were still shopping for homes. And getting turned away.

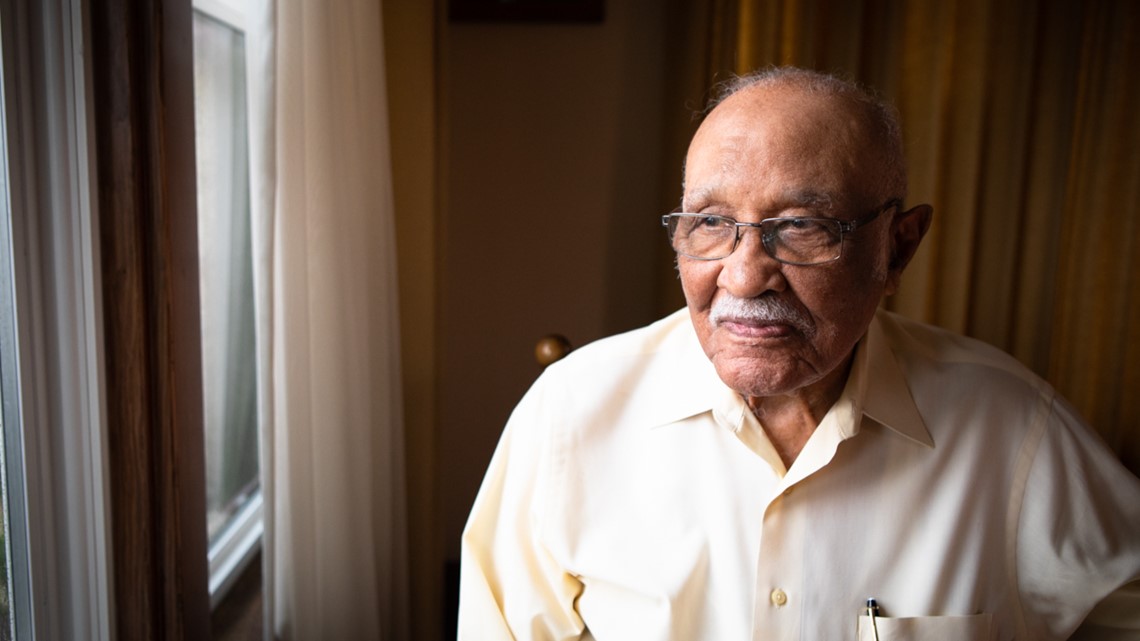

Inewsource spoke at length with two men who once encountered racial covenants and prevailed against them. One of them is Tom Hom, who is 94. The other is Leon Williams, now 99.

Hom was born in San Diego, and he's of Chinese descent. Williams, born in Oklahoma and raised in Bakersfield, moved to San Diego after high school, in 1941. He is Black.

Hom was 19 in 1947, the year his mother decided to move the family to North Park from Logan Heights. The family had a wholesale produce business where they worked “long, hard hours,” Hom said.

They weren’t wealthy, but they had enough for a down payment. They found a roomy house for about $12,000 that had been vacant for a while. It belonged to a dentist and his wife, and then it became a lodging house during World War II.

By the time the Homs were eyeing it, it was something of a project.

“The paints were all peeled away and some of the sideboards of the house were out. And the plumbing system wasn't working adequately,” he said.

His mother and their real estate agent pursued the house, despite concerns that it might have had a racial restriction, like many homes in North Park at the time. Hom said their agent told them the area had a covenant.

Inewsource was unable to independently verify that property had a racial restriction, but did find almost 100 lots in the subdivision across the street from his house and in an adjoining subdivision, all with restrictions added shortly before the Homs tried to move into the neighborhood.

Some of the earliest racially restrictive housing covenants targeted Asian Americans. A Washington Law Review article says “the first case involving the enforcement of a restrictive covenant was decided in California and concerned the right of a Chinese to lease a laundry site in San Diego.

In 1892, the Circuit Court of the United States for the Southern District of California refused to enforce a covenant in a deed that the grantee should never rent the property ‘to a Chinaman.’"

As a teenager, Hom felt that same hatred, that same ignorance.

“A lot of military, during World War II, they'll come up and say, ‘Hey, you're Japanese.’ I say, ‘I'm not. I'm Chinese,’” he said.

So when her family came up against another instance of racism, his mother politely pushed back. She took her youngest son by the hand and knocked on every door in the neighborhood to introduce herself and promised her children would be well behaved, Hom said.

“Come over to the house and have tea with us,” she added. Hom said her real estate agent, who was white, went with her.

What kind of person was this woman? Hom answered with the story of how she once handed over the bills in the cash register at the family’s store downtown to an armed robber.

Then she chased him down the street and flagged a police officer when the robber got onto a bus. “Pretty tough gal, but very nice,” was how he put it.

The family moved in and stayed for decades, and most people didn’t give them trouble.

“The next door neighbors tried to get a petition to enforce the covenant law but the other neighbors weren’t interested, so we stayed there. My mother lived there until she died,” he told the San Diego Reader in 1982.

Wiese, the San Diego State history professor, said covenants were difficult to enforce.

“Imagine just trying to get a group of neighbors together to go to court and to pay the costs of a lawyer,” he said. Legal enforcement reflected a sense from individual neighbors “that they could win, that they should win — or that maybe it was best to sell.”

That didn’t stop some people from trying. In 1944, three Black residents were sued by two white neighbors in Golden Hill.

‘Human beings are human beings’

The same year the Homs bought their North Park home, a World War II veteran named Leon Williams was also shopping for a house. He had seen several properties and landed on one — in Golden Hill.

It had a big yard, perfect for a family. Then Williams spotted the racial covenant in the deed.

Williams had been told “no” before. That should come as no surprise.

After he served in New Guinea and fell gravely ill with malaria, he made it back to the U.S. and spent time on a military base in the South.

“I got on the bus, and they thought I should go in the back. I just sat down in the bus and someone said to me, ‘You’re supposed to go in the back. Don’t you know you need to go in the back?’” There, he growled, then switched to his gentle retort: “‘No, I didn’t know! I’m like anybody else!’” and laughed.

Later, in the late 1960s, as he watched race-based violence unfold across the nation, he felt he had to act. He ran for City Council and became its first Black member in 1969. Then he became the first (and only) Black member of the County Board of Supervisors.

If others have tried to tell him no, he’s turned a deaf ear.

“I've never been intimidated by anything,” Williams said, adding: “I never felt like an outsider of humanity. I never felt inadequate. I never let other people's attitudes embarrass me or put me down. (What) they thought, you know, that's their problem.”

All this may explain his reaction when he discovered the house had a covenant designed to keep him out. Essentially, he shrugged.

“Well, I saw it, it was in the papers, but I didn't pay any attention to it,” Williams said. “Because I always had an attitude that human beings are human beings, and that's other people's limitations if they have those kinds of prejudices and ideas. And so I just ignore them, you know?”

The seller, an elderly woman, lived out of state. On the phone, race wasn’t mentioned.

“She might not have known,” Williams said. “I didn't ask her if she knew and I didn't say anything. I just talked to her like a human being.”

Williams said they were the only non-white family on their street.

He understands why other Black families didn’t feel safe questioning or ignoring covenants.

“People didn’t want to be harassed or have trouble. People could be mean, too, to you. They could be physically mean to you. They can come to your house and talk to you and threaten you,” he said.

But, he added, he didn’t see things that way.

“I wasn't afraid of anything. I just did what I needed to do,” he said.

Seventy-four years later, he’s still in that house, and that investment keeps paying dividends. Golden Hill is one of San Diego’s most diverse neighborhoods today.

His house is worth more than 100 times what he bought it for. The block he lives on picked up an honorary title in 2017: Leon Williams Drive. He loves stepping out onto his balconies — he has three — and taking in views.

After pushing back, they changed the system

Today covenants may be unenforceable, but their legacy remains — even as that era recedes.

“There are fewer and fewer people alive now who have had any kind of practical interaction with these covenants,” Wiggins said.

Her 26-year-old law school students are “really floored” when she gets to the lesson about racial covenants.

“They've grown up in a very different world; in a world that has put a premium on inclusion, fairness, openness, acceptance. And it's like speaking about something that happened on Mars to them.”

In northern California, one community has decided to proactively confront its past.

Marin County, with a population of about 260,000, established a program this summer that helps homeowners research their property’s history and file deed modifications. They received 32 modification requests since the program launched, and now they’re boosting outreach.

San Diego County’s Assistant Recorder/County Clerk Val Handfield said San Diego will have a program “as detailed in Assembly Bill 1466. The specifics of the program will not be known until we have completed the research and developed our program, which we plan to start in early 2022."

The new law requires title companies, real estate agents and other entities to tell buyers if their property has a racially restrictive covenant and to help them get rid of it. It also requires “the county recorder of each county to establish a restrictive covenant program to assist in the redaction of unlawfully restrictive covenants.”

State Assemblymember Kevin McCarty, the bill’s sponsor, was motivated by a covenant tied to a property he was buying, which his agent pointed out in the closing documents. McCarty is biracial. His wife is Hispanic.

“And that just blew me away. I just, wow. I had no idea that those words still existed,” he said.

“I knew they weren't enforceable, but these words still have meaning, you know? It just reminded me that so many people were locked out of homeownership during those early years. And so I thought to myself: Wow, those words shouldn't exist,” he said. “Maybe one day someone will have brought a law to change that. Lo and behold, 21 years later, it’s me that writes that law to change it.”

The killing of George Floyd was the more recent spark, he added.

Hom himself battled covenants as a real estate agent, inspired by his own family’s experience.

A Japanese doctor wanted to move next door, but Hom suspected that lot also had a covenant, so he told the doctor about how his mother went door to door to introduce the family.

“So he did the same thing. And so he was able to build a house there, next to this house,” Hom said.

A few years after he moved to North Park, Hom got tuberculosis. He stopped working at his family’s produce company and became a real estate broker.

He got spillover business from white brokers who didn’t want to do business in some parts of the city. He would take his clients to these upscale neighborhoods and when they pointed to the house they wanted, he’d approach the owners with offers.

“Most people weren't interested in selling, but sometimes they would go ‘What do you think it’s worth?’” That’s when he’d make his pitch. “I told them, ‘It’s for a Chinese family, that they have a good business. … They're good people.’ And that's how I sold houses, good houses, to these people.”

It’s been a long time, but Hom estimated he sold a dozen properties that way in Banker’s Hill and other neighborhoods.

Sellers continued to add racist language to deeds for decades after 1948. Agents kept directing certain buyers from certain neighborhoods.

And a new kind of discrimination, sanctioned by the federal government and carried out by financial institutions, arose to replace covenants: redlining.

Instead of blocking, point-blank, someone from buying a property, redlining made mortgages and insurance so expensive for some buyers that they were effectively shut out once again.

The two methods, redlining and covenants, operate “at different pressure points in the system,” but they have been “equally destructive,” Wiggins said.

Former U.S. Rep Lynn Schenk experienced a vestige of covenants about 25 years after they were outlawed. Her real estate agent steered her and her husband away from the La Jolla Shores area when they were house hunting in the 1970s.

“It was just all rumor,” she said, that the area was not welcoming to Jews. She and her husband are Jewish, she added.

“Even though it was no longer enforceable, it was still what they used to call gentleman's agreement, being enforced,” Schenk said. They switched agents and bought the house they wanted anyway.

A few years later, Schenk made it a priority to dismantle California’s redlining laws when she served in former Gov. Jerry Brown’s cabinet as California's Secretary of Business, Transportation and Housing.

“One of the early things that Governor Brown and I did was to make anti-redlining a top priority,” she said. “We created this anti-redlining division. And I had anywhere from one to three people that just focused on that — that was their full-time job: to eliminate redlining. And to make sure we could write laws that we would introduce to the legislature.”

Identity based exclusions touched many facets of life, she added. “It wasn't just the housing issue. It was everything that surrounds it, in the community.”

She remembered visiting a greeting card shop and asking the saleswoman where the Jewish New Year cards were.

“And she looked at me like I had stung her. And she said, ‘Well, we don't sell those kinds of cards here a lot.’ I'll never forget the tone. And I said to her, ‘You know what? You will, you will.’ You know? And that shop is gone and I'm still here,” Schenk said.

Inewsource reporter Kate Sequeira contributed research to this report.