SAN DIEGO — As temperatures continue to soar in San Diego, it's important for caregivers to keep a close eye on those who are more vulnerable in the heat, including seniors.

"These are important people in the community, they're important in our lives. It's somebody's father, it's somebody's mother, someone's spouse, and every family member's number one priority is keeping their loved ones safe," said Chris Schneider, Director of Communications for Alzheimer's Foundation of America.

Schneider said the elderly, particularly those living with Alzheimer's or dementia are at even greater risk during this heatwave.

"For someone living with dementia, because of the way it impacts the brain, [it makes them] more susceptible to things like heat stroke and dehydration," he said. "That's why caregivers need to be proactive and have a plan."

He offered the following tips:

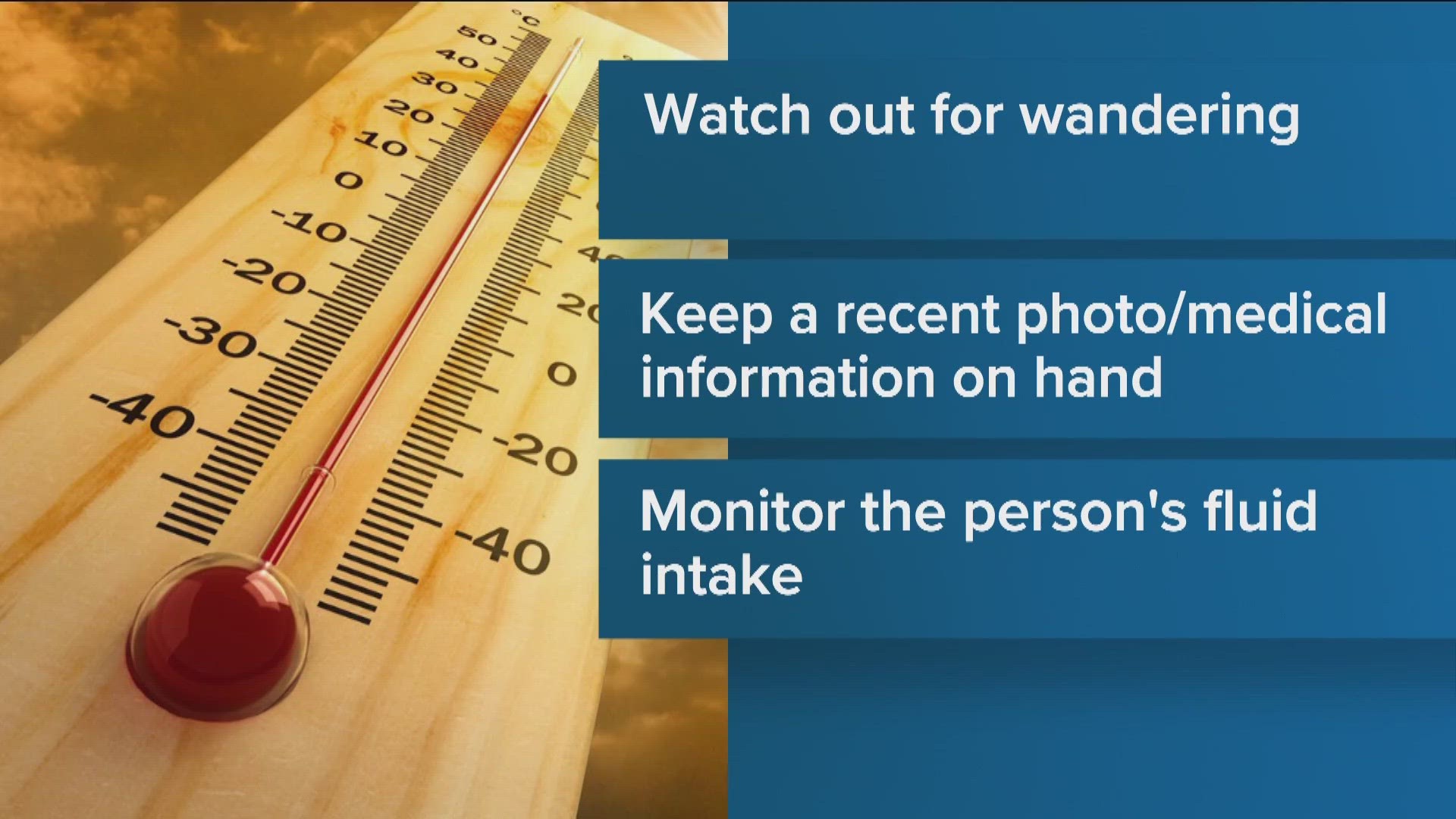

Watch out for wandering. Wandering is a common and potentially dangerous behavior for individuals with dementia, as they can get lost or become disoriented, and not know how or who to call for help. It’s even more dangerous in extreme heat conditions, where heat stroke (a serious elevation in body temperature that is sparked by exposure to extreme environmental heat or a mixture of heat and humidity) can develop in minutes. There are many reasons why someone with dementia wants to go outdoors. Being outside may provide a feeling of purposefulness or satisfaction; be a response to excessive stimuli, be triggered by the need to get away from noises and people; or is a response to an unmet need (i.e., hunger, thirst, boredom). Reduce the chances of wandering by identifying consistent and sustainable ways to support these experiences in a safe environment: create walking paths around the home with visual cues and stimulating objects, engage the person in simple tasks, or offer engaging activities (i.e., music, crafts, games). Ensuring basic needs are met can also reduce the chances of wandering.

Keep a recent photo and medical information on hand, as well as information about familiar destinations that are currently, or formerly, frequented, that can be shared with emergency responders if the person wanders. This will expedite search and rescue efforts.

Watch out for wandering. Wandering is a common and potentially dangerous behavior for individuals with dementia, as they can get lost or become disoriented, and not know how or who to call for help. It’s even more dangerous in extreme heat conditions, where heat stroke (a serious elevation in body temperature that is sparked by exposure to extreme environmental heat or a mixture of heat and humidity) can develop in minutes. There are many reasons why someone with dementia wants to go outdoors. Being outside may provide a feeling of purposefulness or satisfaction; be a response to excessive stimuli, be triggered by the need to get away from noises and people; or is a response to an unmet need (i.e., hunger, thirst, boredom). Reduce the chances of wandering by identifying consistent and sustainable ways to support these experiences in a safe environment: create walking paths around the home with visual cues and stimulating objects, engage the person in simple tasks, or offer engaging activities (i.e., music, crafts, games). Ensuring basic needs are met can also reduce the chances of wandering.

Keep a recent photo and medical information on hand, as well as information about familiar destinations that are currently, or formerly, frequented, that can be shared with emergency responders if the person wanders. This will expedite search and rescue efforts.

Monitor the person’s fluid intake. Alzheimer’s disease and other dementia-related illnesses can affect a person’s ability to know when they are thirsty, thus making it critically important for caregivers to monitor fluid intake and encourage them to drink frequently. Avoid alcohol and caffeinated beverages, as these drinks may contribute to dehydration.

Observe the person for heat stroke warning signs. Dementia-related illnesses can make it harder for a person to detect temperature changes, putting them at greater risk for heat stroke. Watch for warning signs such as excessive sweating, exhaustion, hot, dry, or red skin, muscle cramps, rapid pulse, headaches, dizziness, nausea, or sudden changes in mental status. If the person is exhibiting these warning signs, such actions as resting in an air-conditioned room, removing clothing, applying cold compresses, and drinking fluids can all help cool the body. If the person faints, exhibits excessive confusion or is unconscious, call 911 immediately.

Know where to cool down. Many municipalities will open up air-conditioned “cooling centers” so that people who do not have air conditioning can go cool down. These centers can include senior centers, libraries, community centers and other municipal/public buildings. If your person does not have air conditioning, find out if there are cooling centers are nearby.

Plan ahead. Blackouts and other power failures can sometimes occur during heat waves. Make sure that cell phones, tablets, and other electrical devices are fully charged. Flashlights should be easily accessible in case of a power failure. Have the emergency contact numbers for local utility providers, as well as the police and fire departments, readily accessible.

Have a long-distance plan if necessary. If you don’t live near your loved one, arrange for someone nearby to check on them. Inform this contact person about emergency contacts, and where important medical information, such as an insurance card, is kept. Make sure your loved one has plenty of water, and has access to air conditioning or other cooling mechanisms.