SAN DIEGO COUNTY, Calif — The incarceration rate for Black youth in San Diego County from 2016 through 2023 was more than 13 times higher than it was for white youth, according to monthly incarceration numbers obtained by CBS 8.

And while discrepancies existed when comparing confinement rates for Latino youth with their white peers, it was far less, with Latino youth being three times more likely to be in custody than white youth.

The disparity in incarcerations at San Diego juvenile detention centers mirrors rates reported across the nation.

Reasons for the disparities, according to one study from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention are complex and include higher rates of single-parent households for youth of color, disparate rates of school suspensions and expulsions, and lower school performance scores, among a myriad of other socioeconomic factors.

An analysis of the county juvenile detention rates did show some improvement in the detention rates of juveniles regardless of race and ethnicity.

The data from the county shows that the Black incarceration rate hit its peak in January 2017 when an average of 45 out of every 10,000 Black youth were held in detention centers to 23 out of 10,000 in March 2023.

The story was much different for white juveniles across San Diego County. In January 2017 when Black youth saw the highest in-custody rates, only four out of every 10,000 white youth were placed in detention centers.

Whereas, Latino youth reached its high point in January 2016 when approximately 11 out of every 10,000 were behind bars. That number dropped by more than half in March 2023, when just over five out of every 10,000 Latino juveniles were placed in county detention centers.

When looking at the average annual population inside detention centers and not factoring in demographics, the number of juvenile inmates in San Diego County has seen a drastic drop since 2016, according to data from the county.

Over the course of the past seven years, more Latino youth have been incarcerated than any other racial or ethnic group. In 2016, on average there were 349 minors in detention centers who identified as Latino. That number fell by more than half in 2021 to a seven year low of 121 Latino youth in detention centers only to climb slightly to 167 so far this year.

Black youth were the next highest group. On average, 131 Black youth were incarcerated in 2016 compared to 69 so far this year.

Meanwhile, white youth saw the largest drop in incarceration over the past seven years. In 2017 there was an average of 100 white juveniles inside detention centers. That number dropped to an average of 20 countywide in 2022.

District Attorney Summer Stephan's Restorative Justice Program

A spokesperson for San Diego County District Attorney Summer Stephan said the office is active in "disrupting what some call the 'school-to-prison pipeline'", a systemic pattern where minors from marginalized communities are forced out of the educational system and into the criminal justice system.

Stephan's office has done so, according to the spokesperson through programs such as the Juvenile Diversion Initiative, restorative justice policies, advocating for crime prevention in schools, and truancy support.

In 2021, Stephan's Juvenile Diversion Initiative (JDI) looks for alternatives to filing criminal charges against youth and at the same time addresses the causes of their criminal activity.

The program, according to Stephan's website does so by declining to press criminal charges in exchange for the youth and their family or guardian to work on addressing the issues that lead to the criminal acts.

"Youth in the (Juvenile Diversion Initiative) who successfully complete the program leave with an understanding of the impact of their choices and avoid permanent and negative outcomes related to the formal criminal justice system, including stigma, labeling, and having a criminal record," reads the district attorney's website.

In a statement about the program, Stephan says that the "data shows that most young people come into contact with the juvenile justice system only once and never get into trouble again. If we can redirect those juveniles from the very start, it spares them the negative effects of having a criminal record and gives them a better chance at success in the future. All youth have the capacity to change and grow from their mistakes and providing them with resources and opportunities in the communities in which they live, provides the best outcome for those youth.”

District Attorney Stephan, according to her website, approaches restorative justice by offering the offender the option of undergoing therapeutic services, educational support, and community conferencing as a way to ensure that both offender and victim are given the support they need.

If completed, San Diego County will provide the youth with a chance to have their arrest record sealed as a way to cut off the school-to-prison pipeline that so many young people in America experience.

(Video posted on the DA's website on restorative justice)

What Advocates Say

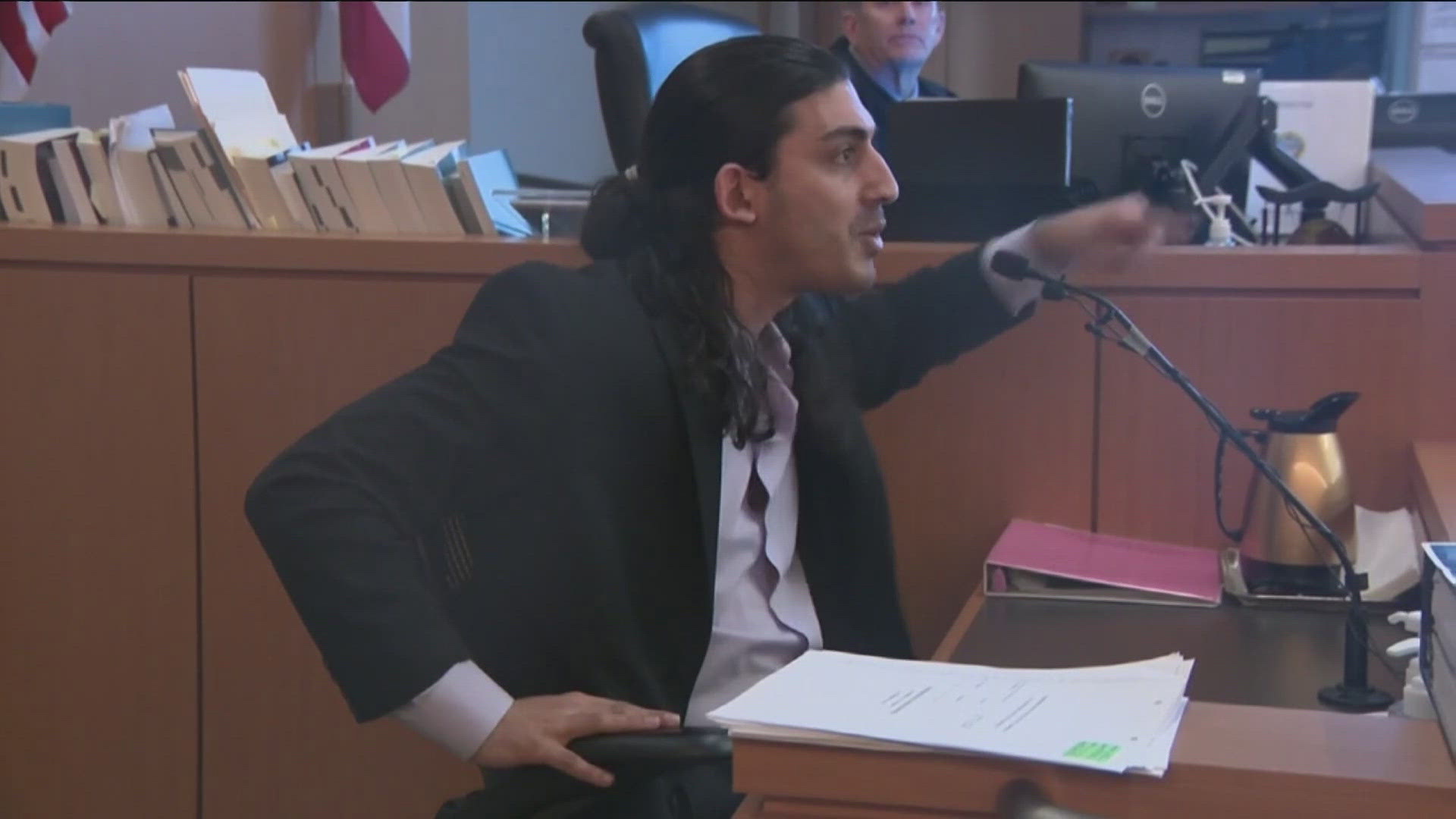

Attorney André Ríos Bollinger specializes in juvenile justice and has advocated for juvenile justice reform. He says that while there has been an effort to reduce overall incarceration rates, little has changed in lessening the racial disparities.

"My first reaction is sadness, and concern over the trauma this inflicts," said Ríos Bollinger in response to seeing San Diego County's juvenile incarceration rates.

"These are roughly the same disparities we see in adults. While sad, this is not surprising. As a community, we continue to invest heavily in law enforcement (including prosecutors) and minimally in programs to meet the needs of at-risk youth," said Ríos Bollinger.

The former public defender turned criminal defense attorney says change needs to start with law enforcement and continue through the courts in order to be effective.

"We position police resources disproportionately in communities of color, so it is not surprising that they then arrest and incarcerate more people of color, whether minors or adults. Schools with large populations of youth of color are more likely to have police officers present on campus, and those schools then refer school discipline issues to the police, rather than handle them as a school problem. This creates a strong school-to-prison pipeline rather than the school-to-college pipeline of whiter (and more affluent) schools."

Ríos Bollinger says that over-policing particular neighborhoods result in an overall distrust from those same communities and a reluctance to work with law enforcement and prosecutors.

Added Ríos Bollinger, "Until we get serious, and consistent, about investing in and funding positive programming for youth in the communities we have underfunded and pumped law enforcement into, these disparities will persist."