New tech helps San Diego Sheriff's Cold Case Unit solve decades-old crimes | True Crime Files

San Diego Sheriff's Cold Case Unit steps into the past and pair old evidence with new forensic techniques to solve murders that might otherwise be left behind.

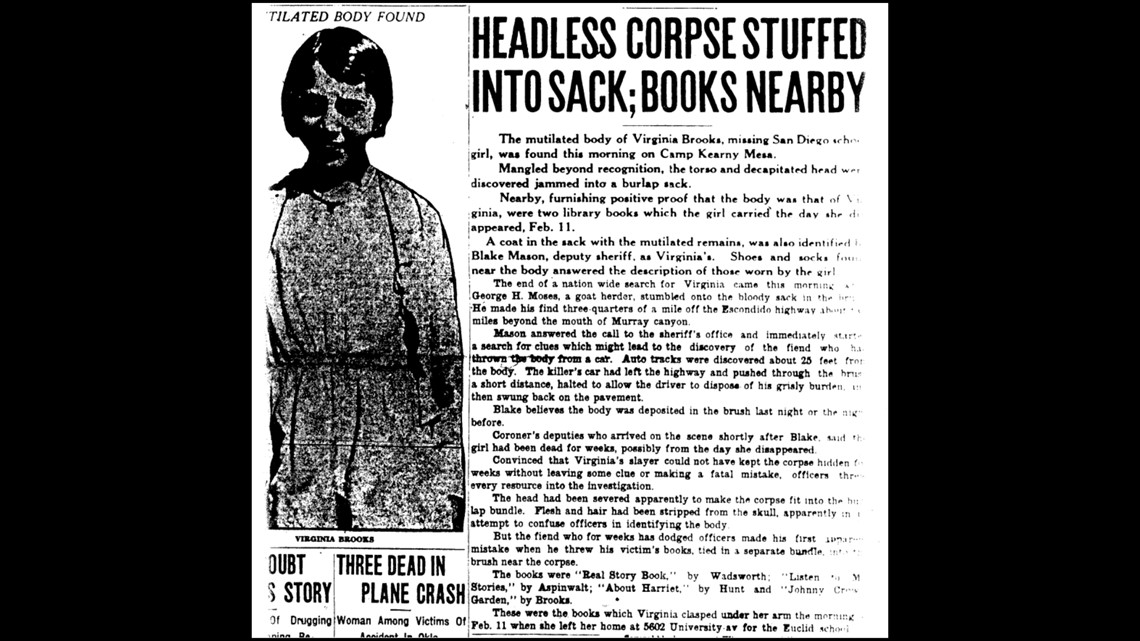

On February 11, 1931, ten-year-old Virginia "Betty" Brooks left her El Cerrito home, carrying books for school and a packed lunch.

Virginia Brooks didn't make it further than 54th Street and University when she was abducted.

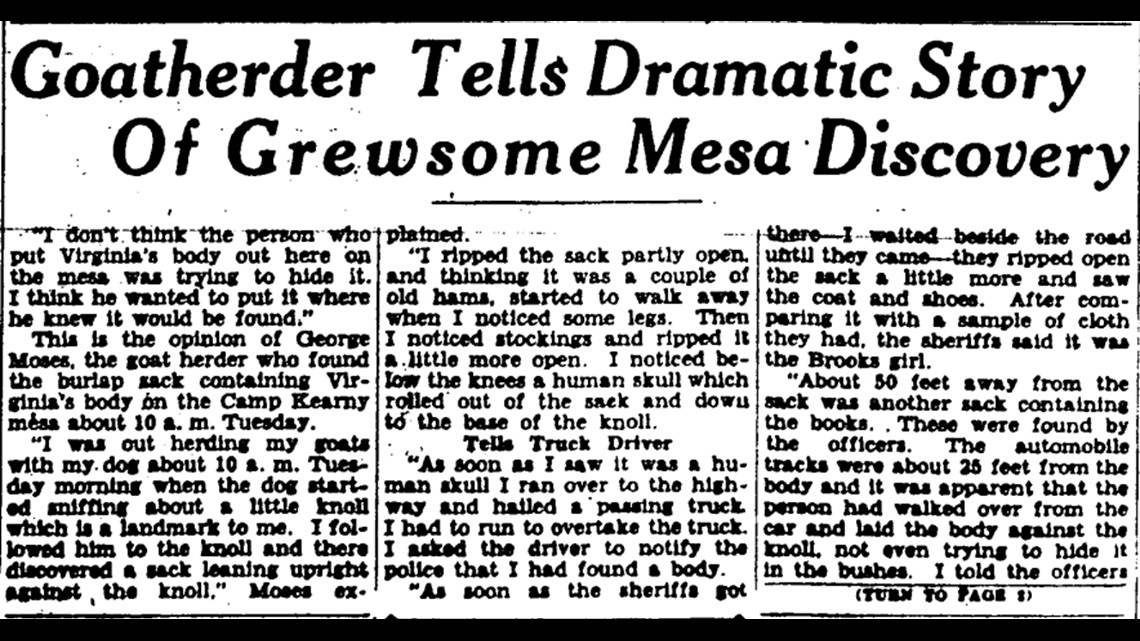

Twenty-seven days later, while herding his goats in what was then a remote area and now the intersection of Kearny Villa Road and Interstate 15, George Moses saw his dog sniffing around a gunny sack propped against a grassy knoll at Camp Kearny Mesa.

Moses told the San Diego Sun on March 13, 1931, that he tore open the sack and found Virginia Brooks' body. Her head was decapitated.

"I don't think the person who put Virginia's body out here on the mesa was trying to hide it," Moses told the Sun. "I think he wanted to put it where he knew it would be found."

For several months, deputies from the San Diego Sheriff's Department and the Coroner's Office investigated a variety of leads, from tire tracks left on the mossy earth that may have come from a Ford truck, to bits of diseased palm fronds found inside the gunny sack, found only in certain areas of San Diego, to a set of cryptic letters left by a person calling himself "The Doctor" under the door at a service station on Winona and University Avenue in what is now City Heights, suggesting more deaths would come.

All leads, however, soon hit dead ends.

The investigation into who murdered 10-year-old Virginia Brooks went cold and remains that way after more than 93 years.

Chasing the Past San Diego County Sheriff's Cold Case Unit

The murder of ten-year-old Virginia Brooks is one of roughly 400 unsolved murders and missing persons that the San Diego County Sheriff's Department's Cold Case Team is tasked with solving. Until then, case notes, photos, and crime scene evidence from Brooks and hundreds of other victims have been laid to rest inside cardboard boxes, stacked neatly inside a handful of small storage rooms scattered throughout the San Diego Sheriff's Department Major Crimes building on Overton Drive in Kearny Mesa.

Meanwhile, the families of those who were brutally and inexplicably killed, many of whom have waited decades for answers, their hopes and questions fall to the San Diego Sheriff's Cold Case Unit. The detectives in this team step into the past and pair old evidence with new forensic techniques to solve murders that might otherwise get left behind.

Sergeant Tim Chantler who leads the Cold Case Team says the work can be a heavy load. It takes heart.

"You can't work homicide without having a passion for solving these crimes," Chantler says. "There's a lot of work. It's a lot of long hours dealing with family members. This is the worst thing that's ever happened to them and their family. If you don't have a passion for it, you're not gonna be successful."

Advances in technology now provide cold case detectives in San Diego County and beyond a fresh start on cases that have otherwise become part of San Diego's dark and lurid past.

Forensic evidence from decades-old murder scenes that were then unusable are now producing DNA matches.

In 2019, the San Diego Sheriff's Department began using Investigative Genetic Genealogy, creating family trees using DNA collected at the scene and looking for partial matches from public databases. Through genealogy, Sheriff's detectives have solved seven cases — six murders and one sexual assault case.

What is Investigative Genetic Genealogy?

Investigative Genetic Genealogy, sometimes called forensic genetic genealogy, is when investigators use crime scene evidence and public DNA websites such as GEDmatch to find killers through family trees.

It's generally a detective's last effort after all other methods have been exhausted.

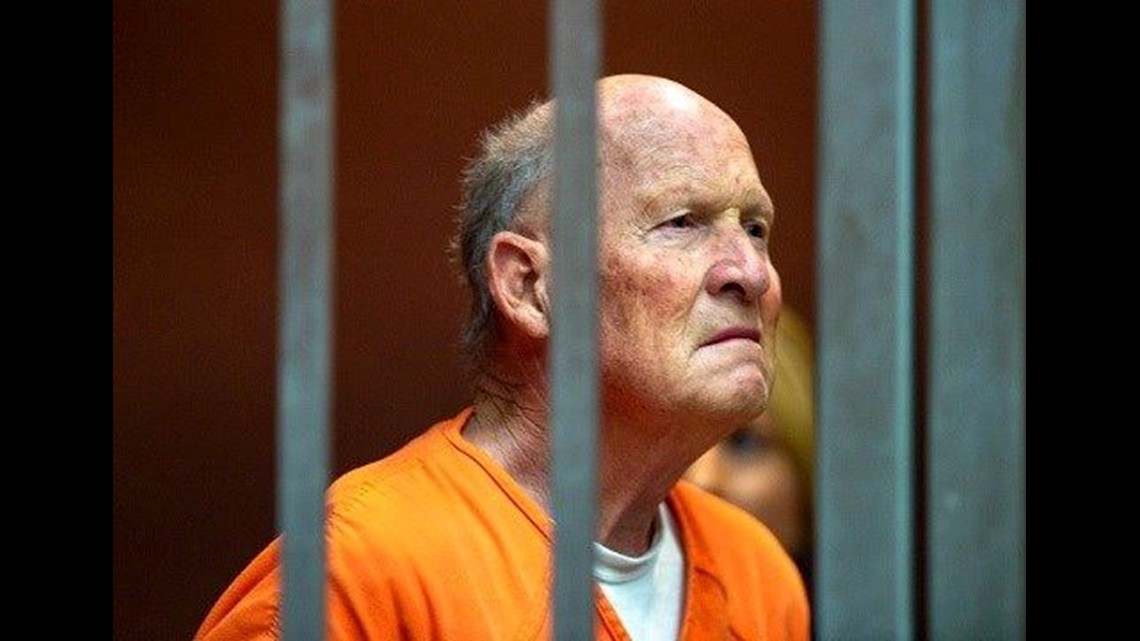

One of the first major cases where IGG was used was in 2018. Investigators tracked down the serial killer and rapist the Golden State Killer, who was later identified as former cop James Joseph DeAngelo.

DeAngelo committed the majority of his crimes in the 1970s and had gone unfound for decades. Investigators used semen collected from the crime scene and used genetic data people voluntarily provided GEDmatch to create a family tree that eventually led back to DeAngelo.

How does Investigative Genetic Genealogy work?

Obtaining the DNA to start building out the family tree is crucial. One "SNP" from a DNA sample gives detectives a profile, which helps them track down relatives, strengthening a complete DNA match as the family tree fills out.

A SNP, commonly called "snips", are single nucleotide polymorphism. It's a small, unique portion within a person's DNA that can be found in their lineage. Think of SNPs as if a portion of a fingerprint's pattern could identify one's ancestry.

They request DNA from those relatives, growing the family tree as they go. It's all above board — detectives identify themselves, explain why they are searching for DNA, explain the process and ask for help. As people consent to provide DNA samples, detectives can expand on the initial SNP and unveil the killer's identity.

Cold Case Detective Brian Patterson says people want to help and they get plenty of cooperation through family members.

"Everybody wants to do what's right," Patterson said.

Santee cold case hits close to home for one detective

Patterson has a close connection to one of those six homicide cases detectives solved using IGG.

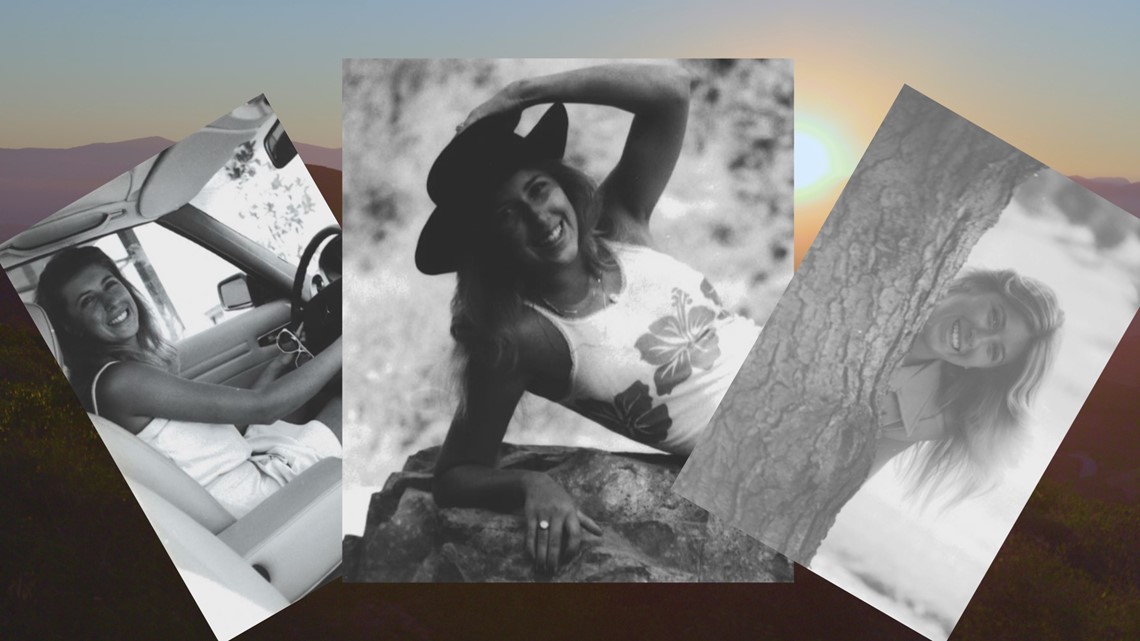

Santee resident Michelle Wyatt was brutally raped and murdered with a telephone chord in 1980 — right on Patterson's newspaper delivery route.

He was 15 at the time. He said he remembers hearing about the murder at the condominium complex he delivered to.

Wyatt was 20 when she was murdered in 1980. The killer entered her home shortly after her boyfriend left in the early morning hours of October 9.

Neighbors heard screaming — but no one called 911.

Detectives didn't have much to go off of at the time. It didn't appear to be a burglary or robbery despite Wyatt's purse contents having been scattered about.

He knew people who were interviewed about Wyatt's murder, he said.

"I don't want to say it gave me more motivation," Patterson said tearfully. "It just hit home."

It took nine months for the Sheriff's Cold Case Unit and the FBI to use IGG to build a family tree that traced back to John Patrick Hogan.

Hogan was 18 when he killed Wyatt. Sheriff detectives say he lived in the same complex as her at one point in time.

Hogan joined the U.S. Air Force a year before he raped and killed Wyatt after graduating from Santana High School. He lived about a mile away from her when she died.

He died when he was 42 — exactly 24 years after Michelle Wyatt's murder — on Oct. 9, 2004.

Patterson said it's a crazy roller coaster. But sometimes they're able to find closure for the victim's loved ones.

"It's a great feeling to go back and tell these families, 'Hey, we finally got the person that killed your loved one.'"

CBS 8 spoke with her parents in 2021, who were in their 80s at the time of the interview. They feared they would die before the truth was uncovered.

“That was my biggest scare of dying and not knowing who did it,” said Michelle's mother, Louise Wyatt.

In CBS 8's next installment of True Crime Files | San Diego County, Sheriff's detectives revisit the shooting death of Sibyl Robbins and the attempted murder of her husband Dr. Harrison Robbins. The shooting occurred as the couple were parked in their car outside of their Encinitas home in 2006.

WATCH RELATED: Cold case solved in 1988 Santee woman’s murder