Up for parole | Convicted Santana High School shooter has a chance at freedom

Due to new laws, Andy Williams is eligible in March 2024. CBS 8 spoke to several people, and no one was aware that a chance for parole could come so soon.

KFMB

WARNING: Some of the content featured in this story is graphic and describes events on March 5, 2001, the day of the Santana High School shooting.

Just after 9:00 a.m. on March 5, 2001

15-year-old Charles “Andy” Williams burst out of a bathroom stall at Santana High School in Santee with a loaded .22 caliber revolver and immediately took aim.

He shot an eleventh-grader in the back of the neck as the student stood at the urinal.

Williams shot 14-year-old Bryan Zuckor in the back of his head while Zuckor walked toward the door. He turned and fired at another student who was using the urinal, hitting him in the chest. He turned the gun on a student-teacher who was at the sink washing his hands, striking him in the abdomen.

Williams opened the bathroom door, positioned himself in the doorway, and fired indiscriminately into Santana High School’s courtyard. He fired at students and faculty members as they ran for cover. Williams shot 17-year-old Randy Gordon in the back near a grassy area behind a nearby building.

Williams re-entered the bathroom to reload his gun. He smirked at a school security guard who was lying on the pavement, wounded.

After reloading, the 15-year-old shooter took his place under the doorway and fired into the crowd.

Sheriff’s Deputies arrived and arrested Williams.

In the end, 17-year-old Randy Gordon and 14-year-old Bryan Zuckor died in the shooting while 13 others were wounded.

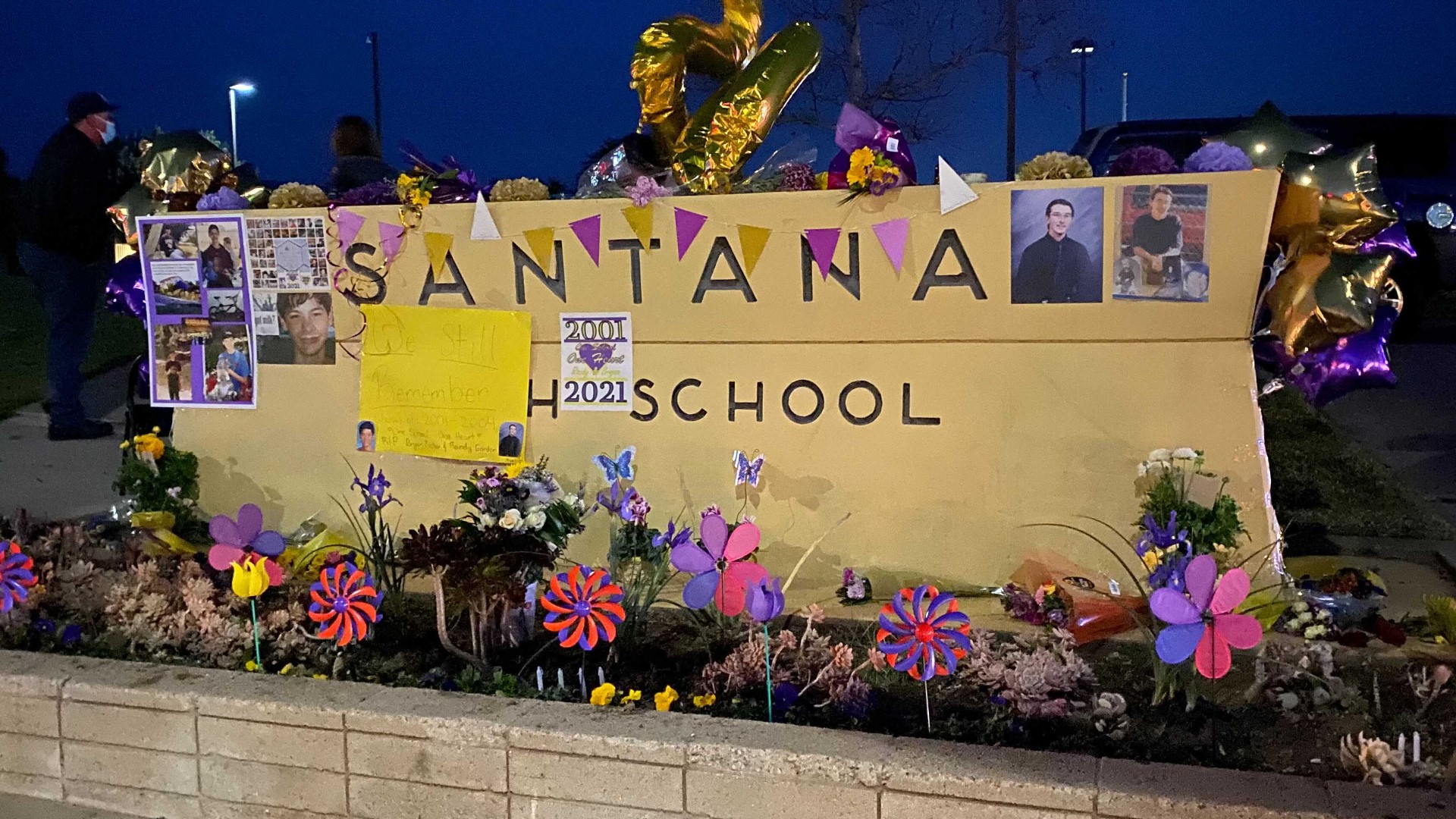

The Santana High School shooting is San Diego County’s worst school shooting in history.

After serving nearly 23 years in prison, having spent more than 70% of his life behind bars, San Diego's deadliest school shooter Andy Williams will be eligible for parole in March 2024.

In the months leading up to that hearing, the hundreds of students who scrambled for safety that day as the cracks from Williams’ gun echoed through the school’s hallways; the parents who sprinted in terror to Santana High School to rescue their children; the 13 students and faculty that were shot, the families of the two boys that were killed, must all face a new challenge.

The challenge is whether a then-15-year-old mass shooter has a right to a second chance.

Once again, the small city of Santee will become the center of a national discussion on school shootings, bullying, and how to deal with school shooters and what their fate should be.

While some see Williams's upcoming parole as a step closer to healing from the scars of a tragedy that has defined their generation and an opportunity to understand Williams’ motivations in hopes of preventing future shootings from happening, others believe Williams hasn’t yet, nor will ever, pay for the pain that he inflicted.

Ahead of Williams’s upcoming parole hearing, CBS 8 interviewed survivors, their family members, and community members, all of whom were unaware of the upcoming hearing.

CBS 8 also spoke with juvenile justice experts who helped craft laws that changed how juvenile murderers and other offenders are tried and sentenced.

In a series of phone interviews from prison, CBS 8 spoke to the shooter, Andy Williams, the then 15-year-old who devastated countless lives and changed the fabric of an entire community about the pain that he has inflicted and how he attempts to make amends for something that can never be forgotten nor forgiven.

In considering whether to interview Santana High School shooter, Andy Williams, CBS 8 considered the impact to the victims and their families, to the survivors whose lives continue to be impacted, and to the community of Santee. After consideration, CBS 8, opted to refrain from Williams' recollection of events from that day and focus on what Williams says he has done to rehabilitate himself in the 23 years since the shooting.

'It just hurts' A mother's unending pain

“At times all I can see in my mind is the image of Andy Williams pulling the trigger while Bryan was walking towards the door. I see that and I feel that pain. I shouldn’t have to feel this. I shouldn’t have that vision. I would do anything to save Bryan that day.”

That was Michelle Zuckor’s response to CBS 8 upon learning of the upcoming parole of her then-14-year-old son’s killer.

“It just really hurts. It just hurts for someone to be gone in an instant and to never come back. Bryan was such a nice boy. He loved life. He loved his family. He wanted a future. He looked forward to his future. He gave one hundred percent to everything he did. He just wanted the best,” said Zuckor.

Zuckor said she has kept her son's clothes and the Lego sets he assembled as a child. It’s all she has left of her son and all she will have.

Zuckor said she was unaware of the laws that now afford Williams the chance at parole.

“I just can’t believe it,” she said.

“It’s not fair because Bryan will never get that chance. I’m just so surprised,” Zuckor said before pausing, “Andy Williams should never have that chance. It’s not like I am not a forgiving person but he took my son and he took my son’s future from him.”

CBS 8 asked Zuckor if she disagreed with the station interviewing Williams.

“No, you have to do it. I understand. I just can’t believe it,” she said.

A student's experience

Annie Vader was a sophomore at Santana High School. More than two decades after the shooting, she remembers the terror on people's faces and the chaos at the school as if it were yesterday. The shooting and the carnage haunt her, with something as minor as a balloon popping capable of triggering a mental health crisis.

On that day in March 2001, just after the first school bell rang at 9 a.m., Vader heard what she thought was a cap gun or fireworks as she stood in the locker tunnel in between the large and small quad.

Seconds later, Vader says she saw a mob of students rushing through the halls, an image which she will never forget.

"Kids started running towards me with terror on their faces. We ran together into the big quad. Suddenly, the shooting stopped for some time, so everyone instinctively ran to the parking lot. Students were screaming and shouting. It is all still so blurry. I can only describe it as genuine terror," she said.

"The amazing thing, something that I will never forget was seeing older kids putting others into the back of their trucks and in their cars to get them to safety. It was one of those moments where innate goodness and humanity appear in the midst of absolute anarchy," Vader said.

It wasn't until later that day that Vader learned that two of her friends had been shot by the same bullet.

"It was all just so much to handle...still is to this day. I have a hard time going places. I fear crowds. I am in a constant state of fight-or-flight. I have a startled response if a balloon pops or I hear a firework. When mass shootings happen, whether at schools or anywhere else, I just have this huge, debilitating feeling of helplessness. It stays for weeks. People don't truly understand how trauma like this manifests itself in people. It impacts everything, not only mental health but a person's physical health as well,” Vader said.

A parent's experience

“Marcy” heard the sirens, more sirens than she had ever heard before. They sounded like they were right outside of her home.

Marcy, who requested anonymity for fear of retribution from community members, took off running towards Santana High School the moment she realized where the sirens were headed.

“That emotion, I'll never forget that emotion I felt that day. It will always be with me. I am trying hard not to cry thinking about it, but I will never forget how that felt. A part of it comes back to me every time I hear a siren. It takes me back to that day, 22 years later,” she said.

Marcy said she replays the scene in her mind frequently.

She remembers sprinting towards the chaotic crowd of parents and students that were huddled in what had become an impromptu staging area in the parking lot of a nearby Alberton's Supermarket.

"I can see right now as if it was yesterday, there was no rhyme or reason. Students were crying. Parents were screaming their children's names. There was nothing organized. It was just...I can't say anything other than chaos,” Marcy said.

Marcy said she darted under the police tape and onto Santana High School's campus where she shouted her son's name.

He was safe but shaken.

"His arms were stiff and stuck in his pocket. I went to hug him. And he didn't hug me back. He was stiff as a board, and he was shaking,” she said.

That night he told her what he saw unfold. Those images stay with her each day, with each passing siren, and with each news report of a mass shooting.

Images of her then-teenage son unknowingly running for cover towards the bathroom doorway where Andy Williams stood. Marcy replays a teacher's arm grabbing her son and pulling him into a classroom. She pictures what her son saw from that classroom, the carnage unfolding as Williams fired into a crowd of students, security guards, and school staffers.

Marcy, however, is not the only person in her family who was left damaged by that gruesome Monday morning in March 2001. Her husband urged her not to speak about the shooting or Williams's upcoming parole.

Her son, saddled by anxiety from the shooting, also asked her not to talk.

"My son has restless legs syndrome. He smokes like a fiend to ease the anxiety,” Marcy said.

But not all are open or willing to consider giving Williams any other chances.

“I choose to think of the students, the teachers, the parents who fell victim, rather than discuss the shooter,” said the community member whose daughter was at the school that day.

CBS 8 spoke to other survivors who were not willing to go on the record.

50 Years to Life Why parole for a killer comes so soon

On June 20, 2002, then-16-year-old Andy Williams, who had turned 15 just prior to the shooting, was tried as an adult and pleaded guilty to two counts of murder and 13 counts of attempted murder.

He was sentenced to 50 years to life.

During sentencing, Judge Herbert Exharos sentenced Williams for the two murders, each carrying a term of 25 years to life. Judge Exharos rendered the prison time for the remaining 13 counts of attempted murder as concurrent, meaning Williams' sentence would not be extended but combined into one.

Judge Exharos did so, according to documents obtained by CBS 8, due to Williams' "youthfulness" at the time of the shooting.

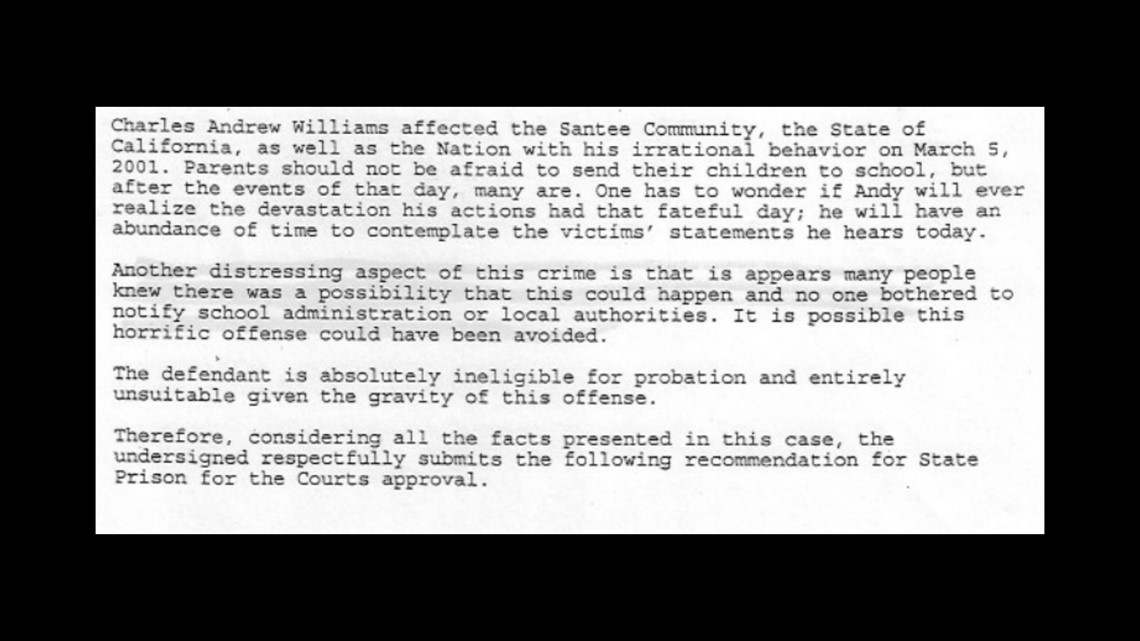

Now nearly 23 years later, serving a few years shy of half of his sentence, Williams is eligible for parole, something that Judge Exharos was advised not to allow to happen.

Those court documents following Wiliams's guilty plea show that the court's parole officer suggested that Williams never be eligible for parole.

But since Williams's sentencing, state laws have changed, and juveniles who were tried and convicted as adults must now be eligible for parole before serving more than 25 years.

The law

In 2013, former Governor Jerry Brown signed the Youth Offender Parole Hearing Bill into law.

That law requires that any person who committed a crime when they were 25 years old or younger be provided with a parole hearing no later than their twenty-fifth year of incarceration.

If the board denies parole, the offender is sent back to prison and in some cases could wait up to 15 years for another parole hearing.

Why the reforms happened

Senior Director of Youth Justice at the National Center for Youth Law, Frankie Guzman serves as a Pacific Juvenile Defender Center Board Member and helped write the Youth Offender Parole Hearing Bill.

Guzman said following the decades-long crowding of California prisons, state lawmakers and voters enacted policies that focused on enhancing and incentivizing rehabilitation for prisoners.

Guzman said since youth offender parole was signed into law in 2013 by former Gov. Brown, roughly 2,000 prisoners have been paroled and released back into the community.

According to Guzman, the Youth Offender Parole process has been widely successful.

“This population has experienced a less than 1 percent recidivism rate, which is exceptional, I would say almost unbelievable,” Guzman said. “They do not commit new crimes, do not create new victims, and do not go back to prison. They overwhelmingly succeed on parole.”

Guzman says that type of ideology didn't exist when the then-15-year-old Williams was faced with the choice between receiving a 400-year sentence or taking the 50-year plea deal that he ultimately accepted.

In 2002, when Williams was going through the court system, state prosecutors had full discretion to prosecute youth offenders as young as 14 years old in the adult court system and sentence them to adult prisons.

However, today, teenagers who commit serious or violent crimes when they are 16 years old or 17 years old can still be tried as adults, but only a judge can make that decision. Cases involving youth 14 years old or 15 years old can no longer be prosecuted in adult court in California.

The Reaction What do survivors and parents think of the upcoming parole hearing

While the laws may now be lessening prison sentences for juvenile offenders, the feelings on whether Andy Williams should be paroled and allowed to have a second chance are mixed.

For the dozen or so people CBS 8 spoke to for this story, there was one common thread; no one was aware that parole would come so soon for Williams.

CBS 8 spoke to former students as well as community members who were at first willing to share their opinions on the matter and then later declined.

"My first reaction when I first heard that he was coming up for parole was to say, 'Throw away the key and don't let him out,'" said Marcy, the mother of a student who ran for cover during the shooting.

But after learning about reports that Williams was severely bullied and allegedly molested, she said that she had a change of heart.

"I just think that if this was my child, I would want him to have a second chance. I would still love my child, no matter what happened, a mother's love never goes away. So, I put myself in his parent's position. Also, my faith has taken me through everything in my life and if he's remorseful, if he did the rehabilitation, if he went to counseling, then I believe anybody can change."

Survivor Annie Vader also has mixed feelings.

"I have learned that Andy Williams was someone who the system, the school, and parents, failed to help. I have empathy for him. I understand the depths and the damage that severe bullying and molestation may have on someone," she said.

However, Vader added, "While I feel that those systemic failures may explain why he did what he did, there's another part that feels outright terror to think of him on the streets, out of prison."

"He sounds like he is way more at peace than any of us are and that is the sad part about this. To think that he probably has had more help in prison, more counseling than any of us have had seems wrong or, if nothing else, unfair," Vader said.

The Media's Coverage of School Shooters

After learning of Williams's upcoming parole, CBS 8 wanted to hear feedback from community members as well as family members of those who were killed in other mass shootings about how the media covered the shootings and the shooters.

Tom Teves's son, Alex, was one of 11 killed in the Aurora, Colorado movie theater shooting in 2012.

Teves created the No Notoriety campaign aimed at holding the media responsible when reporting mass shootings. Teves believes the media should limit what it reports about the shooter, their background, and motivations. Doing so, said Teves, could prevent glorification, sympathy, or those seeking to do similar.

"Take a picture, take a picture of all your kids, and decide which one you don't want there anymore," said Teves in an interview. "Once you lose a child, the pain doesn't go away."

Teves said giving mass shooters platforms can motivate others to try and do the same.

"They want news coverage," Teves said. "They want to be on the front page of the newspaper, or on TV. The media pays more attention to manifestos and guns instead of what happens after, what the shooter does and has done since."

CBS 8 asked Teves for his thoughts on covering Williams’s upcoming parole hearing and his attempts at rehabilitation.

“Focus on what he's trying to do now. What the media doesn't focus on enough, in my opinion, is what happens afterward. You see all kinds of stuff about the guy with the gun, his manifesto, and all that other stuff. But you don't see anything where they normally end up. One reason for that is that they normally end up in a morgue. Unfortunately, in my case, I wasn’t lucky enough for that to happen,” Teves said.

Searching for answers Learning from tragedy

On March 5, 2001, the then-15-year-old Williams took his father's gun from a locked cabinet and wrote a suicide note to his father apologizing for what he was going to do. In the letter he included the first few verses of the Linkin Park song, "In the End."

Just what did Williams feel as he was scribbling the lyrics to Linkin Park’s song, the lyrics that would serve as his goodbye to his father?

“Were you crying? Were you upset when you were writing this,” CBS 8 asked Williams.

"I felt more determination and release at that moment before leaving for school," he responded. "I didn't even contemplate the fact that other people's suffering was getting ready to begin. At the time, my suffering was getting ready to end. Either I was going to show up on campus and shoot myself, point the pistol at someone, and have responding officers shoot me, but somehow, someway my suffering was going to end."

During the interview, Williams navigated the two conflicting aspects of his upcoming parole: his unforgivable, indefensible acts that day and his desire for a second chance.

“As we get closer to your parole hearing, why do you feel like you deserve another chance?,” asked CBS 8.

"There's nothing I can do to ever deserve a second chance. There's nothing I can do to ever merit that. Bryan [Zuckor] and Randy [Gordon] don't get one. But I do believe that I'm worthy of one. I'm okay advocating for myself because I believe that the person that I've become will be a part of the solution. If afforded the chance, I would do my part to promote healing, and try my best to work to prevent gun violence in schools,” Williams said.

So, what drove Williams to do what he did? What drove him to become a 15-year-old who sat emotionless in his room writing a suicide note to his dad, knowing that in just a few hours either he or others would be injured or dead?

Williams on moving to Santee

Williams moved to Santee from Twenty-Nine Palms with his father in September 2000, just six months prior to the shooting. Williams said it wasn't long until the friends that he made started to bully him, in some cases lighting him on fire, punching him in the face, and throwing his backpack in the trash.

“Tell me your experience with bullying after moving to Santee,” asked CBS 8.

"It started with just name-calling," said Williams. "It progressed. At first, kids would come up to me and sock me in the arm, and then they would slap me in the stomach until it progressed to them just punching me in the face. I didn't know how to deal with it. I was at the skate park one time and the kids behind me sprayed me with lighter fluid and set me on fire.

"One day I got pushed into a pool and every time I tried to swim to the side, they would whip me with towels. And so, I literally had to doggy paddle in the middle of the pool until my friends got tired of whipping me and let me get out. I would go to school and get the same thing at school. So there really wasn't any escape," he said.

Adding to the bullying, in October 2000, Williams said that his friend's mom's boyfriend began sexually assaulting him and his friend.

Williams said that man is now serving a life sentence in Oklahoma for molesting other young boys.

Williams said he declined to tell anyone of the molestation prior to the shooting or during the criminal proceedings before he pleaded guilty.

"He would grab our butts and grab my junk. Anytime that he drove us anywhere or bought us alcohol or cigarettes, he would make us kiss him on the lips. It was super confusing for me, like a 28-year-old, grown-ass man preying on 14-year-olds. And again, it was confusing to me because I had a lack of identity. Like, I know, I'm not gay but I let him do it to me to get the things I wanted," Williams said.

Williams said rumors began circulating at school.

"They would say, like, 'Andy you're gay' and it became even more of a lightning rod, and I became even more of a laughingstock,” Williams said.

The Pain A meeting with the school counselor

On March 2, Williams and his father were called in to meet with a guidance counselor at Santana High to discuss Williams's high number of unexcused absences.

During that meeting, Williams said he pleaded with the guidance counselor to allow him to leave school and go to a continuation school.

"I told him that nobody cares about me. I told him that kids are stealing my stuff and I'm getting made fun of in class. Like, it's just not working out for me. I remember the guidance counselor was dismissive and was like, 'Boys are gonna be boys,' and that I was going to have to toughen up. And so that just completely reinforced in my brain, like, nobody cares about me. And like, this was the one time I've ever tried to reach out for help. And it was completely rejected,” he said.

Williams told CBS 8 that the meeting sent him over the edge.

It was that Friday, March 2, that he decided to "make a statement on the following Monday."

"I was like, 'I am going to show them, they can't pick on me anymore,'" Williams said.

That weekend, Williams and two other friends devised a plan to shoot up Santana High School on Monday, March 5.

They told other students about their plans.

By the morning of the shooting, as Williams was writing his suicide note to his father, the other students came to their senses and decided not to go along with the plan.

Many others knew or had heard about the plan to shoot up Santana High. In fact, Williams told CBS 8 that approximately 72 students gave statements to police that they knew or were aware of the plan beforehand.

The state's investigation into the shooting confirmed that others knew as well.

"Another distressing aspect of this crime is that it appears many people knew there was a possibility that this could happen, and no one bothered to notify school administration of local authorities," reads the investigation from the Parole Officer who worked on the 2001 criminal case, before concluding, "it is possible this horrific offense could have been avoided."

The Upcoming Parole Hearing March 2024

Since stepping into prison more than 22 years ago, Williams has undergone many changes.

He changed from a small 15-year-old boy to a 37-year-old adult.

After a bout of substance abuse in his early twenties inside prison, he began attending college, he obtained two Associate of Arts degrees and is now going to school for a bachelor’s degree in Sociology, with hopes of becoming a counselor.

Williams has worked with author Phil Chalmers on strategies to prevent school shootings. Chalmers did not respond to CBS 8’s request for an interview.

And while Williams told CBS 8 that he has worked to accept the pain he has caused, CBS 8 asked him just what he has done to make up for the ripple effect that he has had on his victims, the families of his victims, the survivors, the parents of survivors, and the entire community.

"I could never ever, ever ask for forgiveness for the harm I caused," Williams said.

"I've already stolen so much from my victims and the community. I know that there is no timetable for forgiveness. And, if forgiveness never comes, then it never comes. I have to be okay with it.”

In doing so, Williams acknowledges that there can be no excuses, whether bullying, molestation, or misguided youth.

Concluded Williams, "It's kind of bittersweet because I get the opportunity to go to college. Bryan and Randy don't. And that's because of me."

"I get the opportunity to have crappy prison meals...

"And like what Bryan's mom wouldn't give to even be granted the chance of having a crappy prison meal with her boy, or what Mary Gordon wouldn't give to spend time with Randy. Like, if I put them on the scale, I would never ever, ever be able to, undo the harm that I inflicted. In so many ways, I don't deserve another opportunity. I think I'm worthy of one, but I would never ever say that, like, I've done something to merit one, or I somehow deserve it."

Williams's parole hearing date has not been scheduled but eligibility begins March 2024.