SACRAMENTO, Calif. — Scammers pulled off one of the biggest suspected frauds in U.S. history while laid-off workers scrambled to survive. A CalMatters investigation finds that the EDD missed red flags and failed to make long-promised changes before the pandemic — and that once the twin crises hit, the state and its top contractors kept making money but were slow to deliver relief.

By the first COVID summer, no one knew who was who. In Nigeria, an oil company IT engineer was allegedly filing for unemployment in California and 16 other states with a slew of fake Gmail accounts. At a desert state prison in Imperial County, an inmate used personal data bought on the dark web to funnel unemployment money to his wife for a $71,000 Audi and a down payment on a house. Along the Pacific coast in Carlsbad, Danny Ramos was one of millions of real California workers realizing that something was going very wrong, as weeks or months went by without the unemployment benefits they badly needed.

“It felt,” Ramos said, “like this was just a big old scam.”

As California unemployment claims spiked 2,300% in the early months of 2020, the state’s top labor officials ricocheted from crisis to crisis, internal communications obtained by CalMatters show. Emails and emergency meeting notes detail how the long-troubled California Employment Development Department became the focal point — and then the punching bag — for state efforts to stave off economic collapse while contending with a historic wave of fraud.

“This is bigger than anything we have ever experienced,” then-EDD Director Sharon Hilliard wrote in an email the day before California shut down in mid-March 2020. “Everybody is moving at the speed of light.”

But soon, Bank of America, the EDD’s unemployment debit card contractor, warned that it might not have enough plastic to print the millions of cards that the agency needed. An assistant in Gov. Gavin Newsom’s office emailed the state’s then-Labor Secretary Julie Su asking what to do about someone fraudulently using his Social Security Number to file for unemployment. A staffer for San Francisco Assemblymember Phil Ting pleaded for help for a constituent so distraught about “the runaround” from EDD that she was suicidal.

All across the country, states were dealing with their own versions of this race to prevent a modern-day Great Depression by getting money to laid-off workers, fast. Nowhere was the challenge more daunting — and the fallout more widespread — than in California.

A year-long CalMatters investigation found that the EDD was primed for disaster by years of failing to heed red flags, stalling reforms and abruptly abandoning a pre-pandemic effort to get ahead of exploding online fraud — issues that rose to the top of political agendas and budgets around recessions, but were never really fixed as governors, legislators and federal regulations changed. Once it all boiled over in the spring of 2020, California got the worst of both worlds: tens of billions of dollars lost to fraud, and workers who lost their financial stability, their homes or, in extreme cases, their lives.

“It’s almost like a pendulum, where EDD has opened up the door, and fraud’s happening,” former California Auditor Elaine Howle told CalMatters this summer. “And then, ‘Oops, oh my God, there’s fraud. Let’s freeze all these accounts.’”

Amid these twin failures of rampant fraud and financial harm to real workers, the EDD and top unemployment contractors Bank of America and Deloitte kept raking in millions of dollars from the state’s troubled system. The bank paid the EDD roughly one-third of the nearly half a billion dollars in unemployment debit card revenue generated from March 2020 through December 2022, according to state data requested and analyzed by CalMatters. The bank told state lawmakers that it still lost $178 million on the contract in 2020 due to card fraud and extra call center costs, but refused to provide CalMatters numbers for later years of the pandemic.

No one disputes that other states also struggled to keep up with the deluge, especially when it came to a first-of-its-kind emergency federal program for self-employed workers. States including neighboring Arizona and Nevada at times saw more unemployment claims than they had workers in the state. Despite being home to Silicon Valley, California was one of many states that struggled with decades-old technology, long processing delays and trouble training new workers while triaging a crisis.

Still, California’s system lagged states with much smaller unemployment budgets in several key ways. It is one of only three states that has failed to offer a direct deposit option for jobless benefits, setting the scene for chaos when EDD debit cards briefly became a scammer status symbol. It’s one of four states that has not changed its unemployment tax system since the 1980s, leaving California’s trust fund in the worst shape of any state’s when the pandemic hit — fueling a rapid descent into more than $19 billion of debt to the federal government.

When it comes to heading off fraud, California was in the minority of states that didn’t cross-check unemployment rolls with prisons, state audits found. The EDD was also slower than some other big states to implement new anti-fraud measures — and, once it did, took an approach so broad that state watchdogs say it trapped hundreds of thousands of real workers.

Those inside the EDD during the early days of the pandemic remember the shock as the whole picture came into focus. Job losses quickly blew past all projections for normal recessions, said Greg Williams, the agency’s former deputy director of Unemployment Insurance.

“The best way I can describe it,” Williams said, “is like going to a gunfight with a squirt gun.”

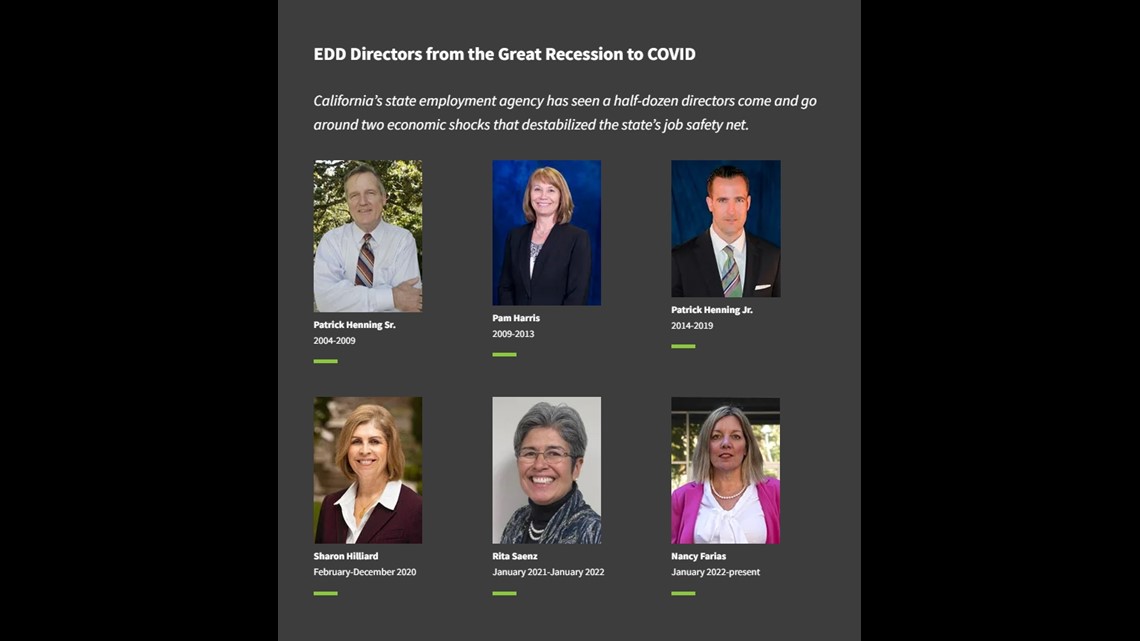

In the decades leading up to the pandemic, tragedy first propelled the EDD from an in-person, paper-based system to a network of call centers and online services that have repeatedly failed under pressure. The agency has lagged federal standards for timely payments and benefit decisions for many years since 2002. An effort to get ahead of online fraud in the 2010s was abandoned even as the risk of cyberattacks mounted across industries.

When the floodgates opened during the pandemic, California took months to tighten application processes, in some cases allowing scammers to more easily file claims than real workers. The EDD cut off benefits for more than 3 million people who didn’t send in requested documents while its offices were piled high with unopened mail. Still, the agency sent out 38 million letters with full Social Security Numbers years after it promised to stop the practice.

The saga set off a political firestorm, adding fuel to the unsuccessful COVID-era campaign to recall Gov. Gavin Newsom. It is still reverberating in a bitter business-versus-labor fight over President Joe Biden’s attempt to make former California labor chief Su his U.S. Secretary of Labor — a move that has drawn fierce partisan opposition. In July, Su, who continues to be the acting Labor Secretary, became the longest unconfirmed nominee whose own party controls the White House and the U.S. Senate.

CalMatters repeatedly attempted to contact Su and Newsom about the state’s pandemic unemployment breakdown, along with former EDD directors Hilliard and Patrick Henning Jr. None of them agreed to an on-the-record interview.

Today, EDD Director Nancy Farias maintains that “we’re no different than any other state.” Shifting federal guidelines for emergency unemployment programs complicated the agency’s response, she said. Once California did start using “fraud filters” to scan for suspicious claims in the fall of 2020, Farias told CalMatters that the EDD took other states’ advice and was aggressive, setting its filters “on the high end” of what the technology could do.

Ultimately, state reports have found that 5 million Californians saw unemployment payments delayed during the pandemic, and at least 1 million saw benefits improperly denied. A backlog of unprocessed claims peaked at around 1.6 million. Hundreds of thousands more workers were cut off by debit card freezes that Bank of America and the EDD blamed on each other.

“People did get caught up, and you know, to be fair, it took us a while,” Farias said of the state’s pandemic unemployment backlog. “But we did go through those claims.”

About 130,000 California workers are still fighting long unemployment appeals cases, and several class-action lawsuits are ongoing against the EDD and Bank of America. To this day, no one knows how much money the state lost to pandemic unemployment fraud; government and industry estimates range from around $20 billion to $32 billion. Some officials say it’s unlikely states will ever know how much was lost to fraud or “improper payments” — a broader government term for intentional fraud and other payment errors — let alone be able to claw back more than a fraction of missing funds.

In the absence of clear answers, the agency now planning a historic $1.2 billion overhaul of California’s job safety net has been left to grapple with big questions. How could the EDD have been so good at giving money to scammers, but so bad at getting funds to real workers? Why didn’t the state and contractors who were making money off of the flawed system do more to fix the problems, faster? And now, who will pay for the fallout?

“My whole life just went upside-down,” said Ramos, the San Diego construction worker, who told a state appeals judge he was forced to separate from family and leave the state for a cheaper rental in Tecate, Mexico, while waiting for unemployment benefits that never came. “They say money doesn’t buy happiness, but poverty sure as hell causes grief.”

The COVID unemployment backlog begins

On March 18, 2020, the day before Newsom first ordered Californians to stay home to slow the spread of the coronavirus, his then-Labor Secretary Su wrote an email to EDD Director Hilliard and her own deputies at the state’s higher-ranking Labor and Workforce Development Agency.

She wanted to know if the state’s unemployment system was ready for whatever came next.

“Do we need to do anything to shore it up at this time to prevent problems (delays or worse — system crash)?” Su asked. “I need you to work together to make sure we are ok.”

At first, the EDD was optimistic: “System is performing fantastic,” the agency’s IT director wrote the next day.

Less than 24 hours later, the scale started to sink in. Su and Hilliard exchanged messages on March 20 about the pros and cons of expediting unemployment approvals by waiving some eligibility requirements. Su wanted to know what keeping the checks in place would mean for processing times.

“How long would it take to get payments out,” Su asked, “and what would the backlog situation likely be?”

Hilliard answered: “It would be months if not well into next year…. Makes my (sic) shiver just thinking about it.”

A bigger challenge was still to come.

In May 2020, California rolled out the unprecedented federal Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program for self-employed workers, which the EDD later blamed for 95% of the state’s COVID-era fraud.

“No,” state websites instructed applicants for the new federal program. “You do not need to submit any documents to the EDD.”

This is where federal officials tasked with tracking what happened to trillions of dollars in nationwide COVID relief spending now say things went awry, both in California and elsewhere. There should have been middle ground — at least doing faster and more obvious checks with prison rolls, or sharing claim information between states — said Michael Horowitz, inspector general of the U.S. Department of Justice and chair of a federal Pandemic Response Accountability Committee.

“They set up a false choice between, ‘Get the money out the door as soon as you can send it out,’ versus, ‘Let’s spend a week matching data,’” Horowitz told CalMatters. “Not months, but a week matching data. And that’s the crux of the problem.”

The EDD maintains that the feds did not provide enough guidance at the time, “leaving states to fend for themselves,” Farias later wrote to a U.S. House committee.

What happened instead as jobless claims flooded in, state reports would later find, was a fateful split in how they were handled by the EDD. About 60% of claims — including many later suspected to be fraud — sailed through an automated application process, a state EDD task force appointed by Newsom found. The application for the emergency federal program for self-employed workers was particularly fast and easy to game, state audits and district attorneys found (sample successful applicant: “Poopy Britches”).

The other 40% of unemployment claims were flagged for manual review for a wide range of reasons, the task force found: typos, nicknames, language barriers, mismatched dates, hyphenated last names, middle initials instead of full middle names, addresses “too long to fit in the database” used by the EDD and so on.

The catch: It was sometimes easier for scammers to get through the automated process than it was for real people. That’s because real people are prone to human error, especially when typing on mobile phones or using outdated online systems.

More proficient scammers, by comparison, use software to copy precise stolen data and auto-file applications, often passing verification even when applications were checked against other government databases.

“Fraudulent applications using these sources will not get flagged,” EDD task force co-leader Jennifer Pahlka wrote in her recent book “Recoding America”. “The data entered on the application will exactly match the sources the EDD checks against, because it is usually a copy of precisely that data.”

Cashing in on EDD contracts

The fraud panic was just beginning, but the chaos that followed would prove to be a money-maker for EDD contractors. That is, until some of them got targeted by scammers, too.

Deloitte — which the state previously paid more than $152 million for projects including an EDD computer modernization effort that state reports found faltered during the pandemic — won another $118 million in no-bid emergency EDD call center and tech contracts after March 2020.

Deloitte spokesperson Karen Walsh said in a statement that the consulting firm has “successfully modernized dozens of state labor and workforce systems,” and that shifting regulations in the years before COVID “required changes” to its work with EDD that increased the scope, time and financial amount of its contracts. During the pandemic, Walsh said, Deloitte helped “deliver critical federal pandemic benefits to millions of California families.”

Things between the EDD and payment contractor Bank of America, meanwhile, were tense. The state and the bank sparred in the early days of the pandemic over how many benefit debit cards it was physically possible to print and provide customer service for.

“They are telling us their limit to issue new cards is 22,500 per night,” EDD Director Hilliard wrote on March 26, 2020. “Starting this Sunday we expect about 465,000 new claimants that will need a card.”

Su was adamant that the bank do more, replying, “We want NO DELAYS in payment of benefits.”

Weeks of emergency phone calls followed. At one point, a plan was hatched, then scrapped, for Bank of America to mail paper checks. State labor officials asked why the EDD didn’t have direct deposit, or online payments similar to Apple Pay’s digital cards. By May, a bank executive wrote that capacity had increased to up to 300,000 cards per day, and that more than 3.8 million cards were active. The two sides bickered about legal and financial agreements.

“This is painful,” one EDD administrator wrote in a June 2020 thread about contract terms.

Still, the mess was minting money for both parties.

Bank of America collected more than $492 million in EDD debit card fees from March 2020 to December 2022, state financial records provided to CalMatters show. Per the state’s debit card contract, the bank kicked back to the EDD nearly $187 million during that same time, which the EDD said was used to help “offset the cost” of administering the state’s multi-billion-dollar unemployment and disability programs.

Under fire for fraud and delays that would plague the system, Bank of America later told the state Senate Banking Committee that, despite the nine-figure revenue, the program was a money-loser, costing $927 million in expenses compared to $687 million in revenue from January 2011 through December 2020. The EDD, the bank argued, was at fault for the system’s security weaknesses.

“The vast majority of fraud occurs when criminals who are ineligible for benefits improperly enroll in the program by creating accounts using false identification or stolen identities,” Brian Putler, a Bank of America government relations executive, wrote to the committee. “The enrollment and cardholder verification processes are controlled by EDD, not by the Bank.”

In mid-2021, the bank went a step further, telling state lawmakers in public statements that it wanted out of its expiring EDD contract; California extended it anyway, in continuity. The following year, the bank was fined $225 million by federal financial regulators for what they called “botched disbursement” of state unemployment funds in California and elsewhere.

The finger-pointing was just starting. In the months that followed, a long-brewing battle would come to a head over whether the state was way too concerned, or not nearly concerned enough, about unemployment fraud.

“The irony is, we went into this pandemic having created a culture in places like EDD of extreme sensitivity to fraud, when in fact it wasn’t that big of a problem,” Pahlka told CalMatters. “And then created the conditions under which we made fraud a really, really big problem.”

A fraud tech boom — then bust

Five years before anyone had heard of COVID, Steve Sheehan discovered a time bomb lurking in the state’s unemployment system.

It was late 2014 when his team of fraud investigators at the EDD started rolling out fraud detection software from a local tech startup called Pondera Solutions.

At his desk at EDD headquarters lofted above the Capitol Mall, Sheehan recalls wading through up to 300 alerts per day for potential unemployment fraud. They flagged possible claims by ineligible prison inmates, on the state’s new unemployment debit cards and applications coming from overseas IP addresses in places like Israel, Uruguay and Pakistan.

“Were we aware that the fraud was out there? Yeah,” said Sheehan, a 30-year EDD veteran who retired in late 2018. “We didn’t put safeguards in place and made California an easier target, so people would come here to do their fraud.”

For a brief period in 2014 and 2015, the EDD used the experimental deal with Pondera as a centerpiece of its effort to finally modernize California’s antiquated unemployment system.

In June 2015, then-EDD Director Henning Jr. gathered with the nation’s top employment officials at a hotel in San Diego to unveil the tech breakthrough: “Fraud Detection As a Service” is what Pondera called the software purchased with a $1.75 million federal grant. Henning Jr., the son of former EDD Director Patrick Henning, was tapped to open the conference, themed “An Ocean of Innovation in Unemployment.”

Within three months, Pondera touted in a case study, the system had flagged $118 million in potential “high value” unemployment fraud cases — a small chunk of the roughly $6 billion California paid out at the time in annual benefits, but which investigators like Sheehan saw as the tip of the iceberg. He advocated to hire more investigators and sign a longer deal for the software, which worked by combing public and private databases to ferret out ineligible applicants and suspicious details, such as recurring addresses and phone numbers.

So it came as a shock, in 2016, when the EDD suddenly pulled the plug.

“It could have been huge,” Sheehan said. “The numbers that we were bringing to the director were in the hundreds of millions, but you need people to pull it out.”

The EDD denied a CalMatters request for documents related to the Pondera contract, stating that it had no such records, despite touting the deal at public events, in press statements and in reports to state lawmakers.

Today, the EDD tells CalMatters in a statement that, “costs were greater than benefits at that time, and the existing system was catching cases flagged by the filters.” It is “not reasonable,” the agency added, to blame states for not predicting a fraud crisis on the scale of the pandemic.

El Dorado County District Attorney Vern Pierson, who led a state insurance fraud working group at the time, remembers meeting with Henning Jr. to learn about the new fraud tool. It seemed like something that was working so well it could be applied to other state systems, Pierson recalled.

While the state attributes the reversal to a lack of renewed federal funding of around $2 million a year, EDD contracts requested by CalMatters show that, around this same time, the Deloitte EDD tech project more than tripled in budget, to $152 million.

“They blamed it on grant money, but the actual truth of it was that the amount of fraud they were detecting was much higher than they were expecting,” Pierson said. “It was just so overwhelming.”

Deja vu

The agency that would become the EDD was born in 1935. Its mission, like similar state agencies across the U.S., was to dole out federal funds to help stabilize a society still reeling from the Great Depression. By the 1950s, California politicians were already sounding alarms about unemployment fraud and lobbying for more money to investigate, according to a CalMatters review of agency records in the California State Archives.

When recessions struck, such as in the early 1980s, state hearings swung in the other direction, focusing more on the social ripple effects of unemployment: depression, suicide, child neglect.

So goes a cycle of dire situations for unemployed workers, fraud panic and social spending fights still playing out today.

But between then and now, California’s economy and the way the state pays out unemployment has transformed. What used to be a system of local field offices, paper applications and checks morphed into a mostly remote system of online applications, debit cards and call centers.

It was a shift driven not just by digitization, but by bloodshed.

In December 1993, former computer engineer Alan Winterbourne dropped off a box of documents at the Ventura County Star-Free Press detailing his seven-year search for work and unsuccessful EDD appeal. Then, dressed in a trench coat, he drove to the Oxnard EDD office and opened fire with a shotgun, killing four people. Police fatally shot him in the parking lot of another EDD office.

“We don’t get combat pay,” Mary Ramirez, a state employee who was in the Oxnard office, told the Los Angeles Times a few days later. “We need every single office separated, so that no one can get into the work areas.”

EDD offices have been closed for most walk-in unemployment help ever since. The lack of in-person support — which now mirrors other state agencies that have digitized services to save time and money — has ratcheted up frustration for those struggling to reach the agency.

The Great Recession that peaked from 2009 to 2011 previewed issues to come: up to 9 out of every 10 workers trying to call an EDD representative couldn’t get through, a 2011 state audit found. From 2002 to 2010, the audit added, the EDD had failed to meet federal standards for the speed at which it paid initial unemployment claims and made decisions about worker eligibility — failures the agency largely attributed to inconsistent staffing and funding in years when unemployment waned.

The breakdowns triggered a major effort to overhaul the EDD through the Deloitte modernization contract, the new Bank of America deal to start paying unemployment via debit cards and the Pondera fraud detection pilot.

Audits later found that, despite the expensive upgrades, employees continued using workarounds on patchy old tech systems that were not well integrated. The Bank of America debit cards, meanwhile, were rolled out without the security chips common in most consumer cards, which the bank told the state Senate Banking Committee was the EDD’s call.

Around the same time, in 2015, Catharine Baker, a former Republican Assemblymember from the East Bay, sent a letter to the EDD about reports that the agency was sending mail with full contact information and Social Security Numbers — sometimes to wrong addresses, sometimes visible through envelopes.

She and other members of a state privacy committee were baffled to hear that three years later, in 2018, the agency still hadn’t fixed the issue, despite withering public hearings and a $3 million budget allocation. Baker asked for a follow-up meeting with then-EDD Director Henning, Jr.

“I remember asking him, ‘If you had all the money that we could give you to do exactly what you want and need to do, how quickly could you do it? Could you do it in 12 months?’” Baker recalled. “He said it would still take five to six years.”

Michael Bernick, who directed the EDD during the dot-com bust of the early 2000s, said the agency always struggled for sustained attention and resources from lawmakers who tend to move on to other priorities when unemployment is low.

“Fraud was never taken seriously,” Bernick said. “Even the fraud that did exist in the early 2000s, you could never get anyone in the Legislature interested.”

The COVID con

Nothing compared to the feeding frenzy once the federal government unleashed $5 trillion in pandemic aid.

In California, Pierson remembers that the initial reports about unemployment fraud were so brazen that some officials wondered if hackers had tapped directly into the EDD’s 1980s-era computer system. The reality, audits and investigations have found, was a more chaotic web of fraud carried out simultaneously by low-level scammers, prison inmates and larger organized criminal groups, plus a few cases of people with connections to the EDD or its contractors.

The most severe national security threats came from hostile nation-state hackers, including the Chinese cyberwar group APT41. By July 2020, the FBI was also warning about so-called “social engineering” schemes, where groups in Nigeria and elsewhere used psychological tactics to try to extract personal information from victims. Amateur scammers everywhere were buying stolen Social Security Numbers on the dark web and social media.

The agency’s best estimates for COVID-era fraud have boomeranged, up to around $30 billion in 2021, then back down to $20 billion. One outside report by government fraud analysts at LexisNexis pegged the figure at more like $32 billion. Comparing how California fared to other states when adjusting for population is difficult, since federal watch dogs have not even published estimates for many states.

As of June 2023, the EDD said in a statement that it had seized or recovered just under $1.9 billion in suspected fraudulently-obtained funds.

“The thing is, it’s every type of fraud under the sun,” said Blake Hall, CEO of identity verification company ID.me, which was hired by the EDD and many other states amid the fraud wave. “You could pinky swear and say that you’re a Lyft driver, and you start collecting, you know, $600-plus a week.”

The EDD and the U.S. Labor Department have clashed over what exactly the agency should have been screening in the early months of the pandemic, internal communications released to CalMatters by the California Labor and Workforce Development Agency show.

In late April 2020, then-EDD Director Hilliard wrote to federal officials about the agency’s decision to suspend its usual requirement that unemployment recipients manually confirm every two weeks that they are still looking for a job.

“Because our benefits system has slowed significantly due to the strain of so many claims and certifications, it has threatened the ability of people to apply for benefits and our ability to pay benefits,” Hilliard wrote, adding that the agency viewed the move to auto-certify approved claims as “consistent with the emergency flexibility that DOL has prescribed for states.”

The feds disagreed: “This is something we expect to be addressed immediately,” a Labor Department division chief responded, calling the waiver a “substantial compliance issue.”

Other states quickly realized there was a problem with the new federal program for self-employed workers. In mid-May, emails show that officials in the state of Washington sent an alert to peers including the EDD saying that they were pausing payments for two days after detecting claims that appeared to use data stolen in a massive 2017 breach at Equifax.

Still, fraud continued to snowball, and California was slow to react.

The agency waited until July 2020 to “make any substantive changes to its fraud detection practices,” the California state auditor found. In late August 2020, the EDD was still processing 120,000 new applications per day, “strongly suggesting automated bulk submissions,” Pahlka wrote. Su has emphasized in congressional hearings that the EDD noticed the spike in August and flagged the practice of automatically backdating claims to federal regulators.

Still, between March and mid-October 2020, the EDD sent roughly 38 million pieces of mail with full Social Security numbers, the state auditor estimated, despite promising to end the practice years earlier.

“There is no sugar coating the reality: California did not have sufficient security measures in place to prevent this level of fraud,” Su said in 2021 — a statement that would later be used against her in the contentious ongoing debate over whether to confirm her as the nation’s top labor official.

As fraud panic escalated, the number of real workers stuck in review or denied benefits also grew — even though Pahlka’s task force found that as few as 0.2% of applicants whose identities were manually verified turned out to be fraud. In 2022, the California Legislative Analyst’s Office wrote that the EDD’s “actions suggest getting payments to workers is not a top priority,” and that the agency “mischaracterized figures… showing far fewer denials” in reports to the Legislature.

One major concern: The EDD denied benefits to 3.4 million workers for not mailing in required documents, even when photos from the time show stacks of unopened mail.

“Each EDD field office had an estimated 450 pounds of unopened mail,” the Legislative Analyst’s office summarized, “and had no system for processing unopened mail.”

Many pandemic claims were approved by the automated system up front, only to be deemed fraud later when federal officials ordered more scrutiny. Some fraud experts criticize the “pay and chase” approach that EDD and other states took. Instead, they question why the EDD, located in one of the tech capitals of the world, waited so long to act to prevent fraud.

California took six months to start using ID.me technology to verify identities through photos and video calls. In October, 2020, amid mass freezes of Bank of America EDD debit cards, the EDD was forced to stop accepting new claims for two weeks to deal with its backlog. In May 2021, the EDD signed a $3.5 million contract for the updated fraud detection software from Pondera — the same promising pilot it had jettisoned five years earlier. After the EDD did act, state watch dogs found that some of the technology went too far, netting hundreds of thousands of real workers in fraud crackdowns.

Some former EDD officials say “Monday morning quarter-backing” cannot account for just how unprecedented the crisis was.

Others worry that the wrong lessons will be learned, and generalized fraud fears will be prioritized over issues for real workers.

And then there are increasingly hard-to-ignore questions, including what California should do about its $19 billion in outstanding unemployment debt to the federal government. Or if any states will ever know how much was lost to fraud, and what happened to workers caught up in the mess.

“If we don’t understand how the money was lost,” said Hall of ID.me, “then history is doomed to repeat itself.”