CALIFORNIA, USA — This story was originally published by CalMatters.

The prospect of an eventual presidential campaign has trailed Gavin Newsom like a shadow for decades — even before he ever became a politician.

In his senior yearbook at Santa Clara University in 1989, his family published a congratulatory message with an eye to the White House: “Gavinsy by George you did it! The next step the Presidency?”

As Newsom runs this fall for a second term as governor of California, a lot more people are asking that question.

With his re-election on Nov. 8 all but assured by an overwhelmingly Democratic electorate and a massive fundraising advantage, Newsom has practically ignored his Republican opponent for months, turning his attention instead to passing abortion protections, defeating a tax on the wealthiest Californians and picking fights with the GOP governors of Texas and Florida.

His increasingly national profile, which includes an appearance last month at a political festival in Texas and helping to raise money for embattled Democratic candidates across the country, has fanned speculation that Newsom is laying the groundwork to run for president — at some point, anyway — despite his repeated protestations that he has “sub-zero interest” in the job.

It has become a favorite line of attack for state Sen. Brian Dahle, the Republican gubernatorial hopeful fighting an uphill battle against Newsom, who couldn’t stop bringing it up during their sole debate on Sunday.

“You all know he’s running for president of the United States. It’s obvious,” Dahle told reporters following the event. “He’s spending money in other states. He’s not focused on California, and Californians are suffering. And I think it’s going to hurt his campaign.”

While Newsom pledged during the debate to serve the full four-year term if reelected, he brushed past Dahle’s swipes and ignored a question about them during a brief gathering with reporters afterwards.

So all that’s clear at this point is that Newsom’s intentions remain unclear. His political aides and advisors continue to insist that his forceful pronouncements of disinterest in the presidency are entirely genuine, though some privately acknowledge that the notion he could credibly run is becoming more real to him.

And his frequent diversions beyond California’s borders in recent months — airing a television ad in Florida in July warning that “freedom is under attack” by Republican leaders, publishing newspaper ads in Texas weeks later to criticize Gov. Greg Abbott’s policies on abortion and guns, renting billboards in six conservative states last month to publicize California’s new government-funded abortion access website — have begun to catch the attention of party activists and political consultants whose support Newsom would need to build out a national campaign.

Bob Shrum, director of the USC Dornsife Center for the Political Future, said that Newsom has emerged as a national leader for Democrats, positioning himself well should he ultimately want to run for president.

“You don’t build a brand overnight. You build it over time,” said Shrum, a veteran adviser of numerous presidential campaigns, including Democratic nominees Al Gore in 2000 and John Kerry in 2004. “You can’t time any of this perfectly, because you can’t know what the future is going to bring. So when you have an opportunity to assert a degree of national leadership, then you assert it.”

A campaign behind the campaign

Of course, Newsom still has another gubernatorial election to win first.

But running now for the third time in four years, Newsom is barely breaking a sweat, displaying little concern for his chances of holding onto the governor’s office for a second term. Since the June primary, when he received 56% of the vote, Newsom has hardly even acknowledged Dahle outside of their Sunday debate, a low-wattage affair that aired on the radio opposite NFL football.

A year after he decisively defeated a recall attempt by more than 20 percentage points, the same margin by which he was first elected in 2018, polls show Newsom cruising to another easy victory in November. A survey released earlier this month by the UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies found Newsom leading Dahle 53% to 32% among likely voters.

So the governor’s attention and campaign resources have, perhaps understandably, been elsewhere.

Newsom went on TV in September as the face of the opposition to Proposition 30, an initiative that would tax income above $2 million to fund electric vehicle incentives and infrastructure. He also recently paid for an ad promoting Proposition 1, a measure to add a guaranteed right to abortion into the state constitution.

Mostly, Newsom seems far more engaged with national issues and audiences, particularly since May, when a draft of the U.S. Supreme Court decision overturning the constitutional right to abortion leaked. His complaint about a lackluster Democratic response — “Where the hell is my party?” he asked at the time — immediately made Newsom a voice for frustrated liberals who want their leaders to stand up more forcefully against Republicans. He has leaned into that indignation ever since.

In one week in September, Newsom attended a climate conference in New York, where he bashed Texas’ GOP Gov. Abbott for “doubling down on stupid” with his commitment to fossil fuels, and then spoke at the Texas Tribune Festival in Austin, where he slammed Florida’s Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis as a “bully” for threatening to fine the Special Olympics for its coronavirus vaccination requirement.

Newsom and his aides insist that he is merely trying to shift attention to issues that are critical to Democratic voters and to put the Republican Party on the defensive, rather than raise his own profile to bolster a future presidential bid.

No one seriously expects Newsom to challenge President Biden should he seek re-election in 2024. But their relationship has appeared to cool in recent months. After reports that Biden allies were irked by Newsom’s leap into the culture wars over the summer, the president endorsed a farmworker unionization bill that Newsom opposed, helping to jam the governor into signing it anyway. Newsom was noticeably absent when Biden visited California this month.

Speaking to reporters in Sacramento in early October, a rare session with the Capitol press corps this year, Newsom said that his experience with the recall election, when state and national GOP figures rallied around the attempt to oust him, had uniquely equipped him to push back on what he characterized as Republicans’ divisive politics.

“So I understand the toxicity of the national discourse, in a way perhaps a lot do but in a more personal way, perhaps, than many,” he said. “I think it’s incredibly important to assert ourselves and to push back and to meet this moment head-on and not be naive about how ruthless the other side is.”

‘The introduction to the dance’

There is an enduring pull toward the White House for California governors, even as none besides Ronald Reagan, who won in 1980 on his second try, has ever come close.

In the past century, Hiram Johnson, Earl Warren and Pat Brown each made multiple unsuccessful bids for president. Arnold Schwarzenegger coveted the job, but was ineligible because he was not born in the United States. The last California governor to run, Pete Wilson in 1995, dropped out before the first primary, hamstrung by poor fundraising and a throat surgery that left him unable to speak for months.

“That’s what politicians do. They’re always moving, in one form or another,” former Gov. Jerry Brown, who made three unsuccessful bids for the Democratic nomination between 1976 and 1992, said in a 2020 oral history of his career. “Anybody who’s running for governor is thinking about being president. Why not?”

Brown said that running from California was a challenge, because candidates need to be relevant to the East Coast, where so many voters are located. One of his mistakes, he said, was not taking more of a national orientation during his first governorship and not selling his story harder to the media outside California.

“If you want to be their leader, you’ve got to be around and familiarize yourself,” he said. “You can spend a lot of money, but the belief that resides in the voters, the pre-existing belief, determines a great deal.”

But Sean Walsh, a veteran Republican political consultant who worked on Wilson’s presidential campaign, said there are potential advantages for a California governor who plays it right. Politicians, their staff and their donors are constantly coming to the state to raise money, he noted, an opportunity to create connections and loyalty with people across the country who could aid a future run.

“You need to have relationships with the movers and shakers in those states,” Walsh said. “That’s the introduction to the dance. It’s the ticket.”

Like many Newsom observers, Walsh believes the governor has maneuvered himself well to quickly jump into the presidential race if Biden decides not to seek a second term for health or political reasons. But Walsh said the timeline for the 2028 election, when there is likely to be an open Democratic primary, couldn’t be better for Newsom, who would be positioned to launch a campaign immediately after leaving the governor’s office.

“The calendar favors you. So be a good guy, don’t get arrogant,” Walsh said. “As long as you are the good soldier for the party,” helping raise money and supporting Democratic policies, he added, “let people speculate about what you want. Let all the talk flourish.”

‘People want a fighter’

One Newsom adviser, in denying his presidential ambitions, said taking up the national culture wars benefits the governor just as much with his California constituents, who want Newsom out there fighting against former President Donald Trump and his brand of politics.

For many others, it seems like an obvious ploy to appeal to the Democratic activists who make up the party base in a presidential primary. Notably, Texas and Florida — Newsom’s most frequent targets — not only have two of the most prominent Republican governors in the country, with rumored presidential ambitions of their own, they are also two of the most delegate-rich states for an aspiring Democratic nominee, after California and New York.

“I think a lot of this is for audiences like me,” said Michael Kolenc, a Democratic political consultant based in Houston. “It’s a really important audience to play to.”

Kolenc said Newsom’s meddling in Texas, which has drawn some return fire from Abbott, is a “sales pitch” to the local Democrats whom he will need to endorse, staff, fund and volunteer for a future presidential campaign and a chance to lock up the best people for his team early. He said Newsom has done a good job getting on their radars and distinguishing himself from other possible contenders with an approach that turns his potential weakness — stereotypes about liberal California — into a strength to troll Republicans.

“You’re taking it to the guy who’s taking it to you,” Kolenc said. “People want a fighter.”

Though there is a political risk that Newsom’s presence in these Republican-leaning states could backfire by giving conservatives another boogeyman to run against, many Democrats give him credit for talking about the issues they yearn to hear about from their leaders, such as abortion rights and gun safety.

“We’re Democrats stuck in Florida. We long to be California,” said Wes Hodge, chairperson of the Orange County Democratic Party, which organizes Democrats in the Orlando area.

Newsom made a minor ripple in Florida with his advertisements over the summer, Hodge said, and though it has since been overshadowed by the state’s own heavily contested races and the response to Hurricane Ian, “it’s never a bad thing to reach out if you want to build your brand.”

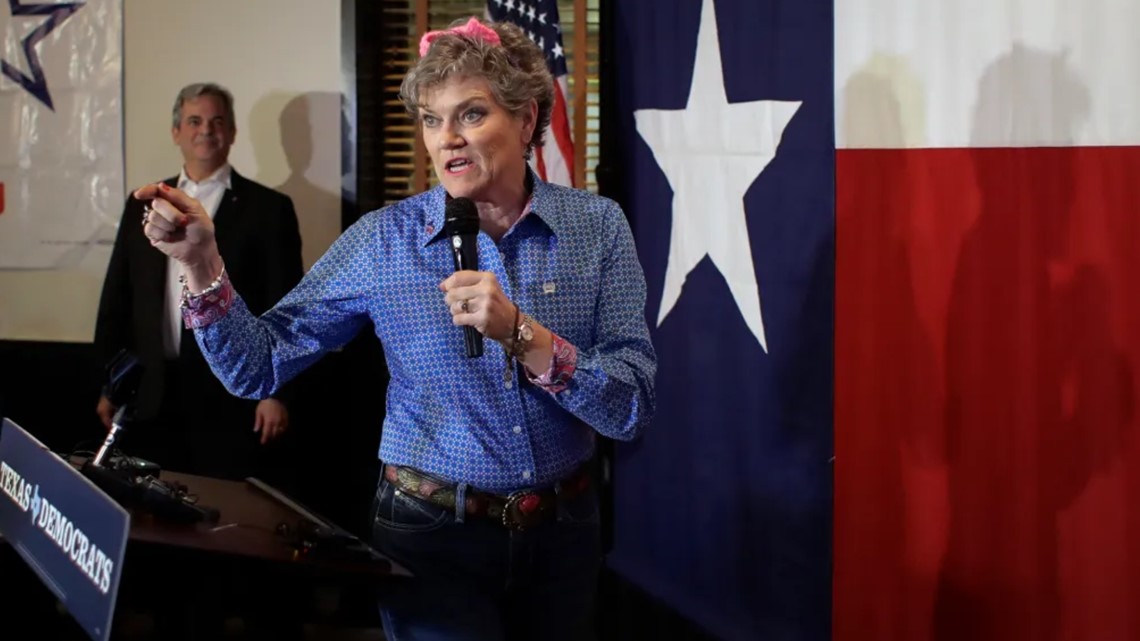

Kim Olson, the Democratic nominee for Texas agriculture commissioner in a close 2018 race, said Newsom is “wise to reach out to a red, rural state…and test-drive his messaging here.” If he runs for president, she said, Newsom will need to figure out how to overcome perceptions that he is a progressive San Francisco elitist and appeal to voters beyond the coasts.

“If he can cut into here, he can probably do it in the rest of the country,” said Olson, who ran unsuccessfully this summer to lead the Texas Democratic Party with the backing of many rural county party officials. “If Gavin can capture that, that’ll kill the elite stuff.”

Olson, who criticizes the national party for not doing enough to support Texas Democrats, said she appreciated Newsom coming to Texas and feuding with Abbott because “it shows he gives a s–t.”

“No one pays attention to Texas. No one helps Texas. We are on our own,” she said. “If you want to come in and bitch-slap some of our Republican guys, knock your socks off.”

In Hidalgo County, the most populous along the border between Texas and Mexico, Samuel Reyes said he is grateful that Newsom, who has called for a federal investigation into Abbott and DeSantis busing and flying migrants to Democratic communities in the north, is providing a missing counterpoint to right-wing narratives.

Reyes, chief of staff for Hidalgo County Democrats, said Republicans have exploited a complicated situation at the border to unfairly portray his entire community like a war zone. While Newsom’s comments may turn off some of Texas’ more conservative Democrats, Reyes said they also help reframe the discussion in a way that gives local party officials more space to push back themselves.

“We don’t want to make it more ugly, but if we do believe in what we’re saying and we do believe that our message is right, then we do have to get it out there,” Reyes said. “I personally like that he’s doing that.”

WATCH RELATED: Newsom signs more than 100 bills in day, more remain on desk (October 2022)