CALIFORNIA, USA — Teachers don’t get into their profession for money or power, but a little more of both might help keep them at high-poverty schools, where students are more likely to fall behind grade level and less likely to graduate from high school or attend college.

Across California and the nation, many of these schools struggle to retain teachers, leaving them with fewer experienced educators. Those who stay often battle the headwinds of poverty: hunger, homelessness and mental health challenges. After only a few years, many end up leaving for easier teaching jobs in more affluent communities.

California’s elected officials have tried for decades to slow the exodus of veteran teachers from schools with the poorest students. One idea that has been conspicuously absent from the conversation: paying teachers more to work at those schools. The politically powerful California Teachers Association opposes “differentiated pay” policies that would increase salaries for teachers at hard-to-staff schools, rendering that approach a non-starter.

Now, lawmakers are making unprecedented investments in two ideas that have been around for years. One offers prospective educators a grant if they commit to teaching at a high-poverty school after their training. The other, a model known as community schools, rethinks school governance, giving more power to teachers to shape every aspect of a school.

Since 2019, the state has spent close to $5 billion on these two approaches. Despite the boost in spending, it remains unclear whether the state will see a return. Teacher turnover remains a perennial challenge at schools serving more low-income families. As experienced teachers leave in search of less challenging classrooms, students at high-needs schools are less likely to have educators who can help close achievement gaps — seen in the persistently lower test scores among those students compared to their more affluent peers. The stakes are now higher than ever as educators work to help students recover from the academic losses they suffered during the pandemic and remote learning.

Staffing is usually overseen by local school districts. But amid the ongoing teacher shortage, State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond said the California Department of Education has “repurposed” one existing employee to help school districts hire teachers.

When he first ran for state superintendent in 2018, Thurmond said he opposed extra pay for teachers in poorer neighborhoods, disputing evidence that it would help. But in a recent interview with CalMatters, he said he would consider any evidence-based policy, especially since some districts already pay some, such as bilingual teachers, more.

“I support any idea that will support teacher retention,” Thurmond said. “We know the profession is impacted by fatigue.”

A CalMatters analysis of teacher experience data from 35 districts — adding up to 1,280 schools — across the state found that the correlation between student poverty and teacher experience is stark, especially in urban regions.

The Golden State Teacher Grant Program gives up to $20,000 in grants to college students earning a teaching credential. In exchange, they work in a high-poverty school for four years within eight years of obtaining their credential. The state committed $500 million over five years to funding the grants, starting in 2021. Gov. Gavin Newsom proposed injecting an additional $6 million into the program this year.

Samantha Fernandez, a 23-year-old single mother from Chula Vista, received $16,000 through the grant program. She said the money covered the entire cost of earning her credential.

“It was a blessing,” she said.

While earning that credential, she worked in two schools in the Cajon Valley Union School District in eastern San Diego County. One had more poorer students while the other was made up predominantly of wealthier ones. The former, Chase Avenue Elementary, serves a large community of immigrants and refugees from Afghanistan, many of whom only spoke Pashto when they arrived. The language barrier was a challenge, but she found the experience to be just as rewarding as working in a more affluent school.

“I want to help kids achieve their dreams, no matter what struggles they go through,” Fernandez said. “I want to be the person who can be their support outside their home.”

Fernandez never set out to work in a high-poverty school, but she said “everything happens for a reason.” It’s too early to know if she’ll stay beyond her four-year commitment, but she said she’s open to it.

In the fall, she’ll start a master’s program in teaching. She said the grant will allow her to continue her education “with a sense of relief.”

This isn’t the first time that California has tried enticing teachers into working at a high-needs school by subsidizing their education. In 2000, the state launched the Governor’s Teaching Fellowship, which gave prospective teachers up to $20,000 in grants for committing to work in a school where test scores rank in the bottom half of the state’s public schools.

The program was short-lived. It ran out of money in 2003. A 2009 study found that about 75% of teachers in the program stayed at high-poverty schools beyond their three-year commitments.

As a reincarnation, the Golden State Teacher Grant Program is attracting applicants in droves. So far, almost 11,000 prospective teachers have committed to teaching at a high-poverty school. The state handed out more than $132 million in grants in the past two years.

None of the teachers have yet completed their four-year commitments, but the state plans to track how many stay beyond that time.

Some research suggests the Golden State Teacher Grant Program could lead to less turnover in the long run. The Learning Policy Institute, an education research group, found that reducing the cost of teacher training can increase recruitment and retention. Tara Kini, the chief of policy and program at the Learning Policy Institute, said the program will help relieve a financial burden on teachers amid the academic fallout from the pandemic.

“The past couple of years have been pretty challenging,” Kini said. “It points to a need for greater incentives for teachers.”

The California Student Aid Commission, the state agency that oversees the Golden State Teacher Grant Program, expects to give out over $157 million by the end of this school year. That puts the state on track to use up the entire $500 million before the 2025 deadline.

Kini said she expects the program to have an added benefit of encouraging more teachers of color — who are already more likely to work in high-poverty schools and carry more student debt — to enter the workforce.

While experience is just one factor, research shows that students do better with teachers who have at least five years of experience. This is where a second statewide initiative, community schools, might help get teachers to stay.

Giving teachers power

Community schools partner with local health or social service organizations to become a one-stop shop for students and their families. Schools tailor the partnerships to what their families need.

The community schools model has been around for decades, but in the past three years, Gov. Newsom and the Legislature poured an unprecedented $4.1 billion into the program.

The state’s investment might not end up in teachers’ pockets, but the money could give teachers at those schools more of a voice at their campuses. Both teachers and experts say that giving educators the power to design lessons and decide how to use a school’s money to help students could be as effective as pay raises to get teachers to stay in challenging work environments.

The community schools model requires:

- Shared governance — Teachers, parents, students and administrators all have a say in every aspect of a school’s operation, from curriculum to after-school activities;

- Autonomy — School communities can make decisions on their own without interference from district bureaucracies;

- “Integrated student supports” — Schools can partner with local organizations to provide health or social services based on the unique needs of their students;

- A community school coordinator — One full-time employee handles administration.

For some educators, the model is an obvious solution to teacher turnover at high-poverty schools.

“A lot of teachers feel disempowered and not part of democratic decision-making,” said David Goldberg, vice president of the California Teachers Association. “They feel like their needs are not being met at schools.”

Giving educators more authority at their workplace makes them feel like respected professionals, said Richard Ingersoll, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania who has studied community schools for decades.

“We’re not making automobiles here. You can’t have one-size-fits-all,” he said. “Those closest to the kids need to be given a lot of discretion.”

Kyle Weinberg, president of the teachers union at San Diego Unified, said making sure teachers have a say in how schools serve the most vulnerable students will help keep them on the payroll.

“We know that when we increase educator voices in school decisions, that educators are more committed,” he said. “They’re more committed to working on strengthening what we’re doing as a school, and they’re more likely to stay at that school when they know they have that voice.”

While districts have a lot of autonomy in designing community schools, implementation can be bumpy.

At Sacramento City Unified, the teachers’ union claims that the district has shut them out of the community schools process. According to teachers union President David Fisher, the district applied for the state grant and received some money, but teachers had no say in which schools were selected.

At Twin Rivers Unified, north of Sacramento, teachers union President Rebecca LeDoux said the district is excluding teachers from decision-making, undermining the key tenet of the community schools model. She said the district chose which schools to turn into community schools without any teacher input.

“My problem isn’t with which schools were chosen, my problem is with how it was chosen,” LeDoux said. “It can’t be through the vision of administrators who sit in the ivory tower, farthest from our students.”

Thurmond said he wasn’t aware of these issues at local districts and said his team would investigate further. Steve Zimmer, a deputy superintendent overseeing community schools grants for the department, said the agency would first try to resolve these issues and only resort to taking away money if there’s a clear unwillingness from administrators to get input from teachers.

“I’m not looking to go to this place… but of course we could take adverse action,” Zimmer said. “I feel confident we’re prepared to make course corrections as necessary.”

There are also success stories. At San Diego Unified, the teachers union and district leaders are clearing the same hurdles materializing at other districts. In April, they signed a contract that codifies the principles of community schools into the bargaining agreements at the 15 schools that received state grants.

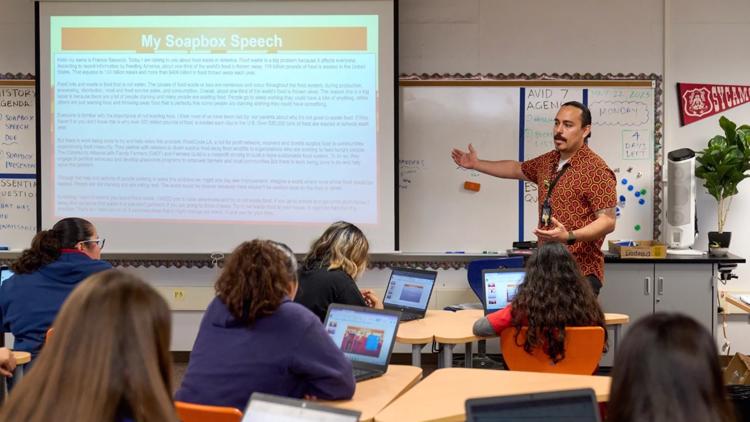

At the Anaheim Union High School District in Orange County, the community schools model has been implemented at 13 schools. At one school, Sycamore Junior High, which serves a large immigrant population, the district used community schools funding to connect parents to immigration legal services and created a social science curriculum focused on immigration policy in the United States. The school also uses community schools grants to host a farmers market once a month on campus.

Throughout the year, teachers assigned “soapbox speeches,” asking students to give a presentation on any social issue affecting students at the school. Topics ranged from immigration and mental health to pet adoption and food waste.

Click here to read the full story.

WATCH RELATED: California bill to increase teacher pay by 50% by 2030 passes committee