CALIFORNIA, USA — This story was originally published by CalMatters.

Smoke and ash from wildfires near Lake Tahoe — one of the deepest lakes in the world — is already clouding the lake’s famously clear water, researchers say.

While the long-term effects are unclear, ash and soot are now coating the surface of the High Sierra lake and veiling the sun, which can disrupt the lake’s ecosystem and its clarity. More debris and sediment are likely to wash into the lake from runoff and rain this fall and winter.

“It’s not going to turn the lake green or anything like that, in my opinion. But certainly the clarity of the lake, how deep you can see in the lake, could be affected for several years,” said Randy Dahlgren, emeritus professor of soils and biogeochemistry at the University of California, Davis. “It all depends on Mother Nature.”

Researchers are now trying to figure out what the residue and flames from the Caldor Fire, which spread into the Lake Tahoe basin on Monday, could mean for the iconic cobalt-blue lake.

“We’ve never had a fire of this extent before…This one is off the charts,” said Geoffrey Schladow, director of the University of California, Davis’ Tahoe Environmental Research Center.

The research center’s tests of the lake already show that its clarity declined in recent days, although Schladow said it may be temporary. The changes could be caused by a combination of factors: smoke preventing sunlight from penetrating the lake’s depths, ash muddying its water or more algae growing near its surface.

“Normally around this time of year, we would expect to see down maybe 65 feet. Right now we’re seeing down maybe 50 feet,” Schladow said.

Over the past half-century, the alpine lake has lost 40% of its clarity, largely due to runoff containing particles and plant-feeding nitrogen and phosphorus. In recent years, its clarity — a sign of its improving health — has begun to stabilize as state and local officials in California and Nevada took steps to protect the lake.

The degree of damage to Lake Tahoe will depend on the degree of devastation to the forest and buildings around it. It also will depend on the months ahead: Severe rain following a fire forces more sediment and nutrients into the runoff and ultimately the lake.

For fine particles, nutrients, and toxic chemicals, “most deposition occurs on the land and continues to be washed into the lake many months after the fires have been extinguished when winter returns,” a 2020 report by UC Davis’ Tahoe Environmental Research Center.

Nestled into the elbow between California and Nevada, Lake Tahoe is a hub of outdoor recreation in both summer and winter, drawing in more than $3 billion in tourism dollars yearly, according to the Tahoe Prosperity Center.

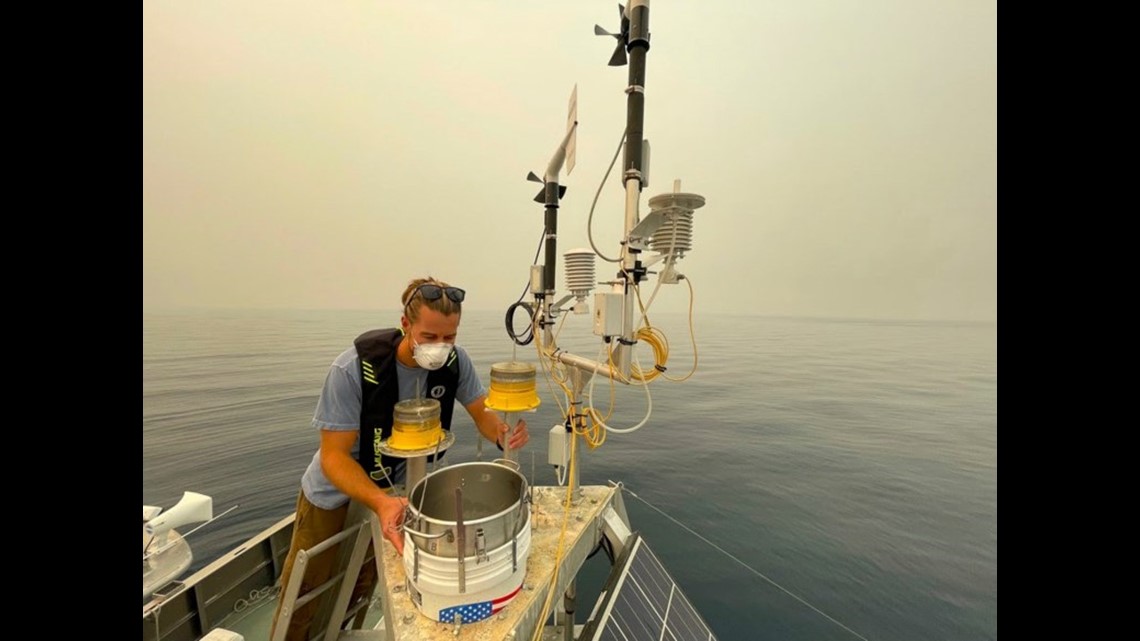

During the fires, Schladow’s team is taking measurements every few days, venturing out on the water to collect water samples and measure UV radiation, water clarity, nutrients and algae.

“The eeriest thing is that here we were at the end of August, on Lake Tahoe. And you could not hear another boat on the lake. That’s sort of unheard of in the middle of the day at Lake Tahoe in August,” Schladow said.

Lake Tahoe and its surrounding lands and waters are home to abundant wildlife, including Lahontan cutthroat trout, which are a threatened species, as well as mountain whitefish, black bears, beavers, marmots, deer, raptors, rare flowering plants and a wingless stonefly that lives on the bottom of the deep lake and provides food for fish.

“I am not as worried about the clarity but the sensitive, endemic (only found in one location) species that are hanging on in the lake…The clarity may be able to rebound but will we lose these species that are already having a tough time?” said Sudeep Chandra, professor of biology at the University of Nevada, Reno.

Alexander Forrest, an associate professor at UC Davis, has launched an autonomous underwater vehicle that seesaws up and down through the water column, crossing the lake once every 15 hours to measure particle sizes and concentrations. His team expects to collect the robot and retrieve its data in a few weeks.

“There’s this sort of layer on the surface and then below, you stir it up with your hand, and you can see these particles drifting around in the water,” Forrest said. “What we’re trying to sort of elucidate or try to understand is, what are the implications?”

Soot and ash, which can wash into the lake if it falls within its expansive watershed, can have different effects on Lake Tahoe’s algae at different depths. Particles can darken the water and cool the lake — making it less hospitable to some algae. But it also can introduce nutrients, such as nitrogen, that algae and other organisms feed on, potentially fueling algal blooms at the surface.

“The whole food web is being turned on its head, I expect,” Schladow said. “The measurements we’re taking (are) to see how true that is and how things are changing.”

That’s what happened at Castle Lake in Siskiyou County after smoke choked the region for 55 days in the summer of 2018, a team of researchers from the University of Nevada, Reno recently reported. Light dimmed in the waters, and temperatures dropped. Algae flourished in shallow waters but dwindled to near zero in the depths. Trout disappeared from the edges of the lake.

“As a result, you completely restructure the internal architecture of a lake,” said Chandra, one of the study’s authors. “The question for Lake Tahoe becomes, does the internal architecture restructure for a short period of time and rebound? Or does it restructure more permanently?”

In recent weeks, the region has been choked with smoke from fires burning throughout Northern California, turning the air hazardous. On Monday, mandatory evacuations from the Caldor Fire spread to South Lake Tahoe, home to resorts that usually are full in late summer.

The Caldor Fire has burned more than 290 square miles of El Dorado County over the past 15 days. The fire has spilled into the Tahoe Basin and is lapping at the edges of the Upper Truckee River Watershed, the biggest contributor to the waters of Lake Tahoe.

“Conceivably, much of the upper Truckee River Watershed could burn,” said Dahlgren. “That’s the worst-case scenario.”

Fires can also contaminate water used for drinking supplies.

Scientists fear that the extreme wildfire season could be signs of the damage that climate change will inflict on waterways like Lake Tahoe in years to come.

“That may be a warning or a harbinger of what the future may have in store for Tahoe and for other lakes,” Schladow said.

“If we’re going to have these big fires every summer, and we start getting these temporary effects every year, at what point does that temporary become the norm?”