Homeless and heartbroken | A housing error reveals cracks in San Diego's homeless system

A family's struggle for disabled housing shows cracks in San Diego's homeless housing system.

Stacey Daggett felt as if it was a new lease on life as she drove to inspect the permanent housing unit that she and her family had been placed into in March 2022. At times, Daggett, her partner Tiran Miller, and the couple’s two young children had thought it would never happen.

The family viewed the placement into permanent housing as a new beginning as well as an end to an extremely challenging two years.

“I was so excited,” says Daggett. “I looked at photos online and the unit looked so nice. I felt relief like this huge burden was finally lifted.”

But on the drive back to Father Joe’s Homeless Shelter after the inspection, the excitement turned to despair, to feelings of dissolution, failure, and hopelessness.

The housing unit that service workers had placed her family into was located on the second floor and not wheelchair accessible – her partner Miller, who is missing both legs and has a terminal heart condition could not make it up the stairs.

Daggett drove to the nearest gas station, sobbing the entire ride. At the station, Daggett gathered her breath and called Miller who was on his way to the new unit with the kids.

“I told him that they placed us in the wrong unit, told me that he wanted me and the kids to take it, and that he would go into a nursing home. He assumed it was his fault, that all this we had been going through was because of him. I would never split up my family. So we decided to go back to Father Joe's.

Now, nearly a year later Daggett and her family are lost in the bottomless vacuum that is San Diego County’s homeless crisis, where the unhoused are forced to feel their way through a dark and unsolvable, multi-dimensional maze, with little hope for a happy ending.

Daggett and Miller and their two children are now in a temporary shelter where they will remain until July. After that, the family will likely be forced back on the street.

They are among the thousands now waiting for their name to be called for placement into permanent housing. They are also among the thousands who are essentially left in the dark with little to no information on when and if that call will ever be made. Daggett and Miller join the thousands of others navigating a system that is pieced together by nearly three dozen service providers, and underpaid case managers, all feeling their way through an incomplete and meandering system.

As for Daggett, she fears that the call may come too late and her young son and daughter will watch their father live out his final days in a homeless shelter or even worse, on the street.

A Twist of Fate A rare medical condition proves to be life-altering

San Diego natives, Daggett and Miller, moved to Arizona for a chance at a cheaper place to live. Miller had a job as an auditor in a warehouse. Daggett worked in finance. The couple had just purchased a food truck and business was taking off when tragedy struck.

On a March day in 2019, Miller complained of a bad headache. Daggett ran to the store for a pain reliever. When she returned, firetrucks and ambulances dotted her street. Miller lay half-dead in the front yard after an aneurysm burst in his heart.

“They told us to say goodbye to him,” says Daggett. “The aneurysm tore his heart open from top to bottom. And so, we kissed him goodbye.”

Miller’s surgeons managed to sew his heart closed. However, as he recovered from surgery, he continued to run a high fever.

“The doctors couldn't figure out what it was. And, because COVID had just hit, I couldn't go visit him,” says Daggett. “I would go online and look at his medical reports that the hospital sent me and I kept seeing this 10-centimeter mass in his chest.”

Daggett told doctors about the mass, but she says they didn’t seem concerned about it.

“He had lost all of his weight. He couldn't open a bottle of water. I remember crying to him. We decided to take him to the Mayo Clinic and they discovered what the mass was, it was a surgical towel that the surgeon had left in his chest.”

The surgical towel, says Miller, had been left inside of his body for decades after a shooting when Miller was a teen in Southeast San Diego.

Daggett says Miller contracted sepsis and doctors had to amputate both legs and open up his chest to remove the towel.

“We decided we needed some help and came back home to San Diego because I just couldn't do it by myself anymore,” says Daggett.

Returning to San Diego Pandemic plus rising housing costs fuels homeless crisis

Daggett says a family friend had arranged for the family to rent a house for only $1,500 a month.

Nine months later, however, Daggett says code enforcement officers showed up at the house.

The landlord had built an addition without permits. Code enforcement workers found black mold throughout the house.

“They basically said we had to go,” says Daggett. “The house was inhabitable. We had no options. That's how we ended up at Father Joe's.”

Homeless in San Diego

The family went to Father Joe's Villages for shelter in hopes they would eventually get placed in transitional housing. With her husband's disability and the fact they have two young kids, Daggett was told it wouldn't be a problem to get into transitional housing.

But Daggett says it was not an easy transition. She feared for her husband's health. The shelter was dirty and unsanitary. She worried Miller would get sepsis again, or some other serious ailment that would surely jeopardize his life.

Daggett also worried about her young children.

"People forget what the kids go through. They're young and they don't really know how to express their emotions," says Daggett. "My kids went from having their own bedrooms and backyard to watching their dad go from building go-karts and taking them camping, and fishing to seeing him in a wheelchair, having to live in a homeless shelter. They have been through so much. I'm so proud of them but I also feel like I'm completely failing to protect them."

In March of 2022, Daggett and Miller learned they would be placed in a permanent housing unit at a Kearny Mesa hotel turned permanent housing that the San Diego Housing Commission purchased through the state's Project Homekey initiative.

Daggett says that because the hotel is owned by the Housing Commission and is a Project Homekey property, Father Joe's no longer worked as their service provider.

Instead, Dagget says she was told to contact Hyder Properties, which managed the property, and after her family was placed, Telecare would provide any services needed.

However, when Daggett arrived at the former Residence Inn at 5400 Kearny Mesa Road, she discovered her family's dreams of moving into a place of their own had turned into a nightmare. The family's unit was located upstairs and was not wheelchair accessible.

With nowhere to turn Daggett and her family returned to Father Joe's East Village Homeless Shelter.

As was the case for so many others, the pandemic placed an added level of hardship on Daggett and her family.

Her 9-year-old son contracted COVID. Daggett urged Father Joe's staff to let the family quarantine in a hotel in order to make sure that Tiran was safe. According to Daggett, when staff denied her request and refused to allow her inside the shelter to get her belongings, she grew incensed. Daggett says the staff at Father Joe's kicked her and her family out after she lost her temper with an employee there.

With no other place to go, the family of four, her partner missing both legs and weak from a terminal heart condition, were forced to live in their van.

"It weighed heavy on us," said Daggett. "Tiran couldn't get the proper treatment in the van. I couldn't change him. It was just it was really, really hard."

Nearly a year has passed since Daggett and her family were placed into the wrong unit. The family has been staying at the Door of Hope temporary shelter in Kearny Mesa and will be until July.

After that, Daggett says she has no idea where the family will go and whether her husband can survive if having to live in the van or in a homeless shelter again.

Cracks in the System Navigating the region's unnavigable homeless system

Navigating San Diego County's homeless services system is no easy task. The system is a patchwork comprised of dozens of third-party service providers that operated independently from one another, all competing for the same pot of funding.

The service providers are tasked with not only finding and allocating housing units but are responsible for updating those eligible for future housing.

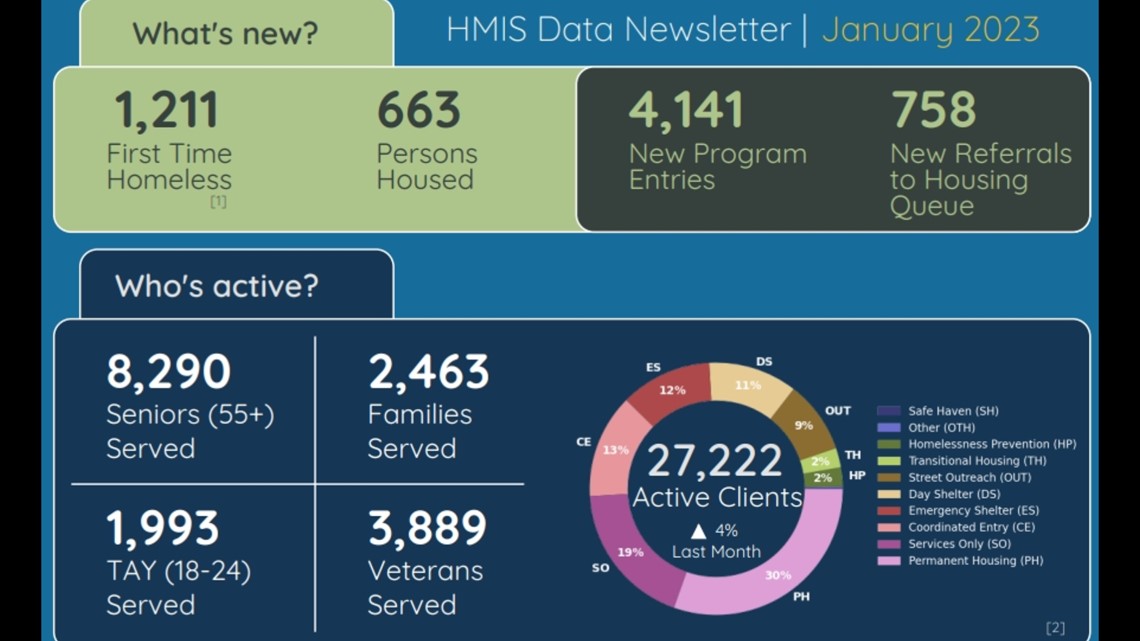

It is a daunting task considering that, according to the Regional Task Force on Homelessness, 663 people were housed in some type of housing, whether transitional or permanent units during January 2023. That same month 1,211 new homeless people entered the system, meaning more people are entering the system than are getting placed into housing. At the same time, the task force says that there are 27,222 active clients who are in need of housing.

On January 27, Daggett says the Coordinated Entry System, the department that keeps track of available housing units, informed her that her family was no longer in line for housing; that they were listed as having been placed.

It is the second major mistake, one that Daggett is unsure how to navigate.

"To this day, we don't know where we are in terms of getting placed into housing," says Daggett. "There are so many people in this system and nobody is talking to each other. It's so easy to get lost in it. I don't even know where we are anymore."

CBS 8 confirmed that the family has since been placed back into the system. A spokesperson for the Door of Hope says they were accidentally removed from the list due to a clerical error. The spokesperson says the family is back on the CES list.

"Not enough units, plain and simple" Housing advocates frustrated and fatigued

"We don't have enough units, plain and simple," says homeless advocate Michael McConnell on the number of units.

Adds McConnell, "If we have a hard time finding information, look at what a homeless person has to go through. You have to maintain contact, being on the street makes it so difficult, there are so many obstacles, and if you do make it through those hurdles the wait list is so long. Some people wait years, for whatever reason that is.

Amie Zamudio has worked tirelessly trying to get homeless seniors and those with disabilities into housing. Zamudio runs a small non-profit, Housing 4 the Homeless.

Zamudio says she has seen dozens of people get misplaced into non-ADA units, some of which are in wheelchairs and barely able to turn around in their tiny studio apartments. They, however, remain silent so as not to ruffle any feathers and jeopardize their housing status.

"We are incredibly short of being able to house any of our homeless let alone those with physical disabilities," says Zamudio.

Zamudio says the county and the Regional Task Force should have advocates with those who are placed to make sure the transition is smooth, something that, she says, is the exception to the rule.

"There's a lot of red tape to work through. And when you're talking about someone that maybe has a disability such as a learning challenge, or is an older adult, getting through those barriers is extremely difficult. We need to take out and remove a lot of the barriers in the system. We have multiple systems that intersect with each other who are not communicating with each other. That is a huge problem. And we've been saying we all need to get into the same room and have this conversation and have different systems start to intersect and have continuity."

The Quest for Accountability A myriad of providers makes accountability a difficult task

CBS 8 spent weeks contacting service providers who worked on Stacey Daggett and Tiran Miller's case including Father Joe's, Telecare, the San Diego Housing Commission, and the Regional Task Force on Homelessness and none provided an explanation as to what happened to the couple's placement and why they were removed from the list.

Scott Marshall, the Vice President of Communications at the Housing Commission, offered some information about the process, while at the same time showing that what happened to Daggett and Miller was the exact opposite of what should happen.

Wrote Marshall, "A household experiencing homelessness is identified through [the Regional Task Force on Homelessness's] Homeless Management Information System and referred to housing through the CES process. If the housing to which they are matched is not an option for them, they are returned to the same position they previously had in CES to be considered for the next available match to housing based on their housing need, as assessed and identified in HMIS."

The Housing Commission's comment further shines a light on what are very dark and deep cracks inside San Diego's homeless system.

For Daggett and Miller, the only light they wish to see is one inside a new home, where they can live together and spend the final minutes of Miller's life with their kids, inside and not in a shelter without any hope in sight.

The family has since started a gofundme drive to help with their housing issues.