SAN DIEGO COUNTY, Calif. — Officially, they are San Diego County COVID-19 death numbers 85, 97, 99, 248 and 297.

To their families, they were the teacher with sparkling eyes and a love for bocce ball. The keen student of history who had survived a U.S. internment camp for Japanese-Americans. The dad to a 9-year-old. The wife of 59 years.

They are now, also, absences and enigmas.

In San Diego County, more than 400 lives have been lost to the new coronavirus since the pandemic struck the region in March, and the crisis is far from over. As San Diegans venture out into public spaces and some resume normal activities, infections are on the rise and people keep dying.

As of Monday, about 44% of those who died in San Diego County were Hispanic or Latino, inewsource found. A third who died were from South County, 56% were male and 87% were over 60 years old. A striking 95% of those who died had underlying health conditions.

In interviews with inewsource, families of the deceased brought up multiple issues that led to the worst outcome for these patients: a veteran didn’t receive a potentially lifesaving plasma therapy on time because the supply was tainted; a woman likely caught the virus from home healthcare workers who tended to her ailing husband; one man was denied testing, despite being sick enough that he died soon after; another contracted the virus while living at a memory care facility; and a merchant mariner was asked to work on a Navy ship without adequate precautions.

Here are their stories. There are hundreds of others — healthcare workers, the disease’s youngest victims, the people experiencing homelessness, those who contracted the virus in San Diego and died in Mexico, the people who were never tested or counted — and the list keeps growing. So does the list of unanswered questions.

Death 99: Tainted plasma

After testing positive for COVID-19, 43-year-old veteran Robert Mendoza drove himself to Tri-City Medical Center in Oceanside, suffering from low oxygen levels. The doctors almost didn’t admit him because his symptoms didn’t seem severe, Mendoza’s parents said — he could still talk and walk fine on his own. But they eventually found him a bed.

He was admitted to the hospital on a Monday in April. About two days later, he was placed in the ICU.

He died five days after that.

“I really — from Monday to Wednesday, I ask myself what could have happened,” said his mother, Yolanda Mendoza.

Her son was known as a fighter and a survivor. He left home at 17 to fulfill his dream of joining the Marines, eventually traveling to Iraq and Afghanistan for battle. After a parachuting accident caused a broken femur and pelvis, doctors inserted a titanium rod into his leg. He rejoined the military after mastering a grueling series of physical tests.

Mendoza’s father, who is also named Robert, said he couldn’t believe “that somebody could go through three wars and survive and come home, and then something you can’t even see can take them down.”

One thing the veteran’s parents hoped would improve his condition came too late: Mendoza had been approved for a plasma therapy, his parents said, but when the plasma arrived at the hospital it was “tainted” and couldn’t be used. Mendoza’s mother said she was given the news by the hospital’s charge nurse, but nobody explained to her how the shipment became contaminated.

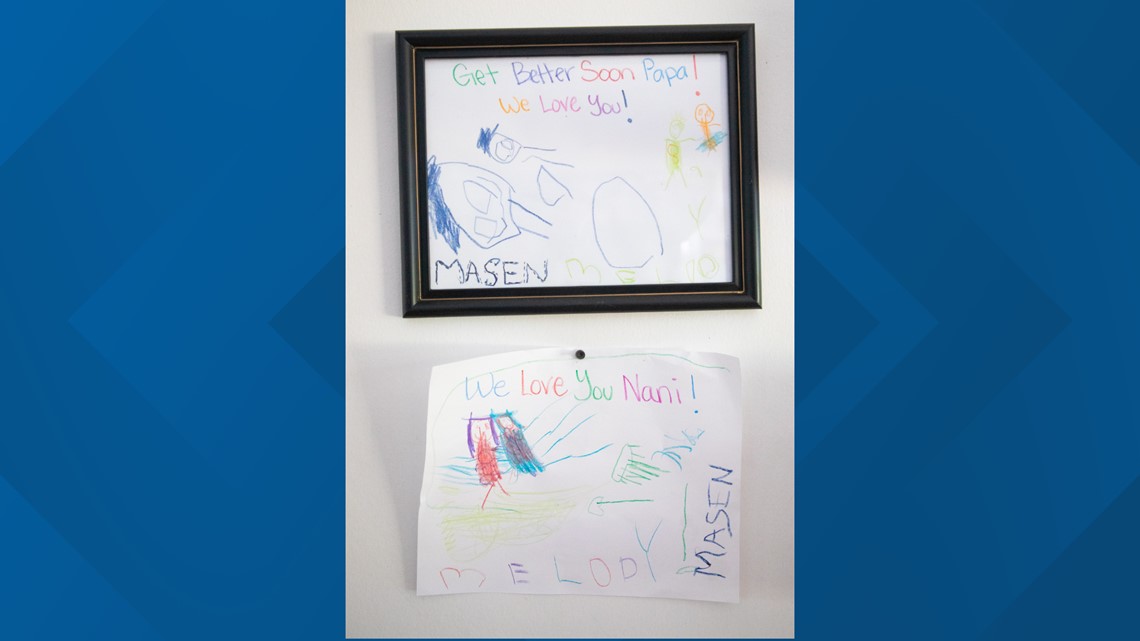

The next order of plasma wasn’t delivered for another day or two, and by then the father of a 9-year-old boy was on dialysis for kidney failure. He died the next morning, on April 20.

“It just makes me wonder if he had received the plasma when he went into the ICU on Wednesday or maybe if he had received it on Thursday or Friday, maybe the outcome would have been different,” Yolanda Mendoza said.

Tri-City Medical Center confirmed in a statement that the hospital is partnering with the Mayo Clinic to offer convalescent plasma therapy, an experimental treatment in which people who have recovered from the coronavirus donate their blood plasma to those who are still sick. The hope is that the antibodies could help severely ill patients like Mendoza fight off the infection.

Aaron Byzak, chief external affairs officer for Tri-City Medical Center, said the hospital can’t comment on what happened in Mendoza’s case because of health privacy concerns. But, he said, “Plasma containing certain antibodies may not be used due to potential harmful effects.”

Though the benefits of plasma therapy haven’t been proven, preliminary research shows some patients have reported positive responses.

As a part of his treatment, Mendoza did receive hydroxychloroquine, a malaria drug President Donald Trump has touted to fight the coronavirus. The Food and Drug Administration briefly authorized the use of the drug for COVID-19 patients but revoked that authorization in June because of emerging evidence that it does not help people who have the virus — and it may even harm them.

As his health worsened, Mendoza’s parents kept calling the hospital to speak with their son. But the busy healthcare workers on the other end were only able to put him on the phone one time, for a video call minutes before his death.

He couldn’t speak, and his parents don’t know if he could hear them saying they loved him.

At Mendoza’s small funeral in Houston, Marines served as pallbearers. His parents have received phone calls from veterans across the globe who served alongside their son, telling them how much they loved him.

“My son had a lot of friends,” Robert Mendoza said. “But I just didn’t realize how many he had.”

Death 248: ‘Little cracks’

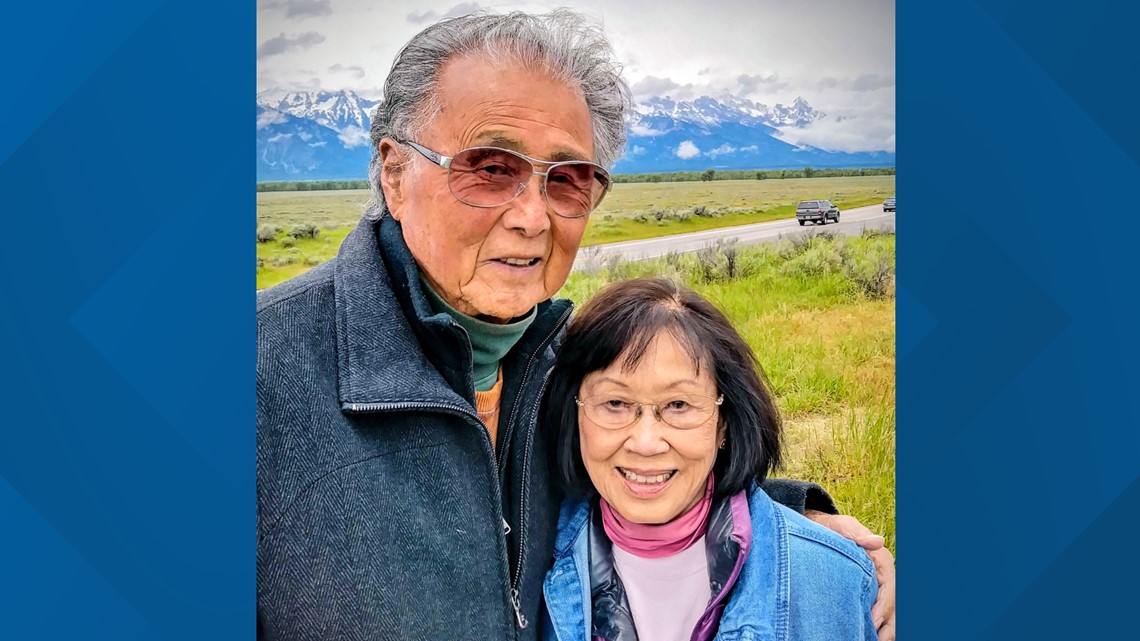

Kent Yamada had built what he thought was a fortress around his elderly parents, with meticulous practices around distancing, disinfection and isolation.

Despite the family’s efforts, Kent Yamada said “little cracks” appeared. At first, they were invisible. Then they couldn’t be unseen.

He believes his mother, Elizabeth Kikuchi-Yamada, contracted the virus from any of the dozen or so healthcare workers who came and left their La Jolla home in March and April to help his father, Joseph Yamada, who had severe dementia.

One man came to talk about getting a hospital-grade bed for Joseph. Two other workers followed up, taking measurements, and a different team delivered it. Another healthcare worker brought oxygen to the house. EMTs entered at one point, and medical educators visited another time to talk with Elizabeth about her husband’s condition.

Some of these people wore masks. Some did not.

Each visitor, and each lapse, added to the risk of infection for Elizabeth and Joseph. Both were 90.

Yamada said he would ask the healthcare workers to put on masks. EMTs wore gloves and other protective gear, but the others did not.

His mother, who he described as “fit as a horse,” didn’t understand how easily the virus could spread — she called it “the COVID” and thought it was a type of flu. But Yamada believes the home health workers should have known better and taken more precautions.

“When you're thinking that you're working with healthcare people, you really do believe that they're professionals and they wouldn't do anything to endanger or take a risk,” Yamada said. “But the truth is that they aren't as serious as you think they are.”

California passed a law in 2016 requiring home care aides to pass background checks and enter an online registry. The state’s Home Care Services Bureau also regulates the care provided by these aides, responds to complaints and conducts unannounced inspections.

In response to the pandemic, the bureau recommended in April that home care aides wear face coverings, not work if they are sick, disinfect objects in the home they’re working in and avoid physical contact with patients when possible. If a client has a suspected or confirmed case of COVID-19, aides are supposed to wear medical-grade masks and other protective gear.

But the bureau has also loosened its rules around some inspections and investigations: Rather than conducting them in person, they can occur remotely. A similar change around on-site inspections at nursing homes has outraged advocates, who claim virtual visits aren’t enough to make sure the vulnerable and elderly are protected from the virus.

Plus, unlike the staff in nursing homes, home care aides don’t have to follow strict testing requirements for COVID-19, increasing the likelihood that asymptomatic workers could carry the virus undetected into their clients’ homes.

Khai Nguyen, the clinical services chief for geriatrics at UC San Diego Health, said healthcare workers need better access to coronavirus testing to protect their patients.

“I think ‘problem’ is an understatement when it comes to testing healthcare workers in general. We need more testing,” Nguyen said. “There's no doubt about it.”

Elizabeth and Joseph, who was a noted landscape architect, had roughly a dozen contacts in the course of about a month.

Rebecca Fielding-Miller, an assistant professor of infectious disease and global public health at UCSD, said each of those people likely had many other high-risk interactions as part of their jobs. Then they went home and possibly exposed their own relatives and household members.

“Of course [the home health worker] needs to be masking and being careful, but that's a lot of risk for one person to be taking on for $24,000 a year,” she said, referring to the average yearly wages for home health aides in 2018. These workers, she added, tend to be from populations that are more affected by the coronavirus, such as immigrants. “There’s kind of a compounding of risk,” Fielding-Miller said.

Workers need to be trained but also equipped to do their jobs safely by their employers, Fielding-Miller said.

“How many masks is this person being issued a day?” she asked. “Are they being given hand sanitizer that they can take to different sites? Are they being expected to bring their own?”

Kikuchi-Yamada died at Scripps Green Hospital in La Jolla on May 20.

In her 90 years, she had survived an internment camp for Japanese Americans, graduated from UC Berkeley, raised three children, taught English at San Diego High School, led a fulfilling life, and still she wanted to live “just a bit longer” to say goodbye to her friends and family, her son said.

But she was not interested in a life without her husband, who died in early May from dementia, her son said. The couple met when they were 11. In the days before Joseph Yamada’s death, his wife had snuggled next to him, dozing and barely eating. The kids thought she was grieving, but she was already sick.

Her death certificate lists three causes: respiratory failure, pneumonia and COVID-19. When Kent Yamada talks with people about what happened, he tells them his mother died of a broken heart.

Deaths 85 and 297: Testing delays

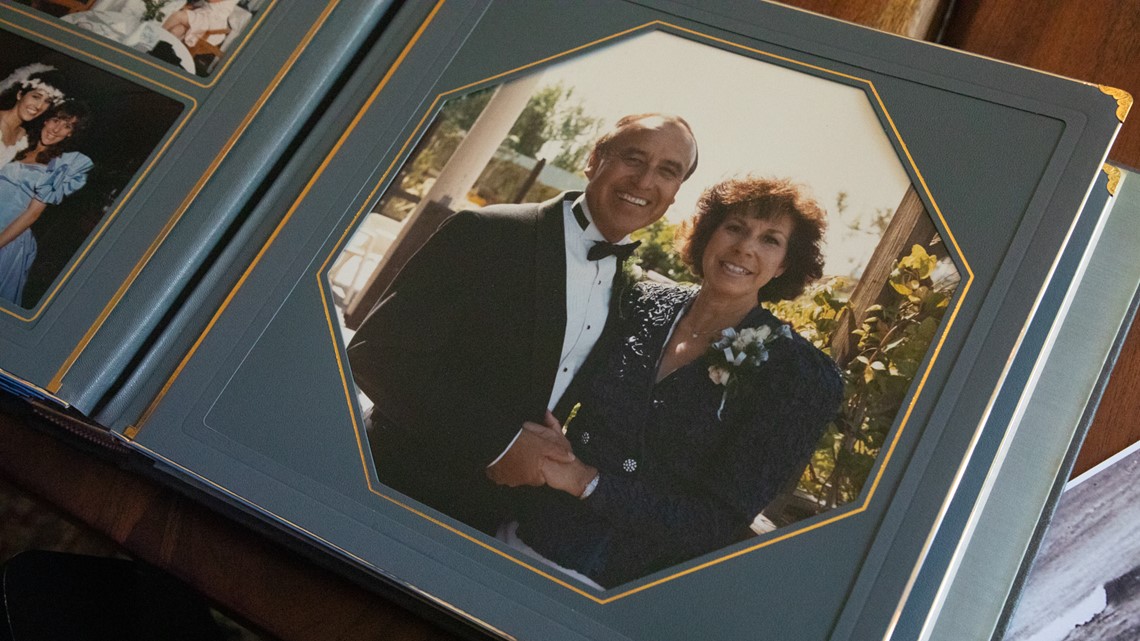

The first in the family to die from the virus was Mona Weiss.

The 88-year-old, a great cook known for her albondigas soup and homemade pinto beans, developed a bad cough and was losing her appetite in mid-March. So her son, Michael Weiss, 54, took her to her doctor at a Scripps Health medical building in Chula Vista.

He listened to her lungs, and told the mother and son it was bronchitis. The prescription: medication to treat it and self-care at home. Although San Diego County already had several dozen cases of the coronavirus, no X-ray and no COVID-19 test was ordered, Michael said.

The second family member to die, a month and a half after Mona, was Michael’s 90-year-old uncle — the husband of Mona’s sister. Though Joe Villegas and Mona had not had contact with one another and caught the virus through different channels, a common thread connects their deaths: Both had trouble getting tested for COVID-19.

In the end, COVID-19 infected at least seven members of the Weiss and Villegas families. The virus — combined with inadequate access to testing and other health conditions — cost them two lives.

After Mona was sent home to her house in Chula Vista with a cough, the virus took root, undetected.

By early April, her son, who had taken her to the doctor, also contracted the virus along with her granddaughter's husband, who lived with her.

Michael Weiss said he was initially denied testing when he asked his doctor for it. He ended up spending 21 days at the Sharp Chula Vista hospital, 10 on a ventilator and sacrificing 28 pounds of muscle mass as he fought the virus. When he was strong enough to hear bad news, he learned his mother had died — and she died alone — of COVID-19.

For Michael and Mona, testing came too late. Both were eventually tested by the hospitals they went to and both received their results on April 11, long after their symptoms started and long after their doctors had first been notified of their health worries.

Nguyen, the geriatrics specialist at UCSD, said testing rates are inadequate, including for older patients who might not appear to be sick with the coronavirus though they are infected.

“We should have low thresholds in checking for COVID-19 in our senior patients,” Nguyen said. “Because aging in and of itself is a high-risk factor. The [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] says that eight out of 10 people who have died from coronavirus have been above the age of 65. That to me is most concerning.”

In a statement, a spokesperson for Scripps, the healthcare system where Mona received her care, said patients with symptoms of bronchitis and other lung infection-related diseases are “likely” tested for COVID-19 and that the decision is made by the healthcare provider.

A lifelong resident of South County, Mona first lived in San Ysidro and later moved to Chula Vista, where she was part of one of the first graduating classes of Chula Vista High School and went on to raise a family with her husband, Lee. She and Lee had a bike business for a time, and she ran her own jewelry business. Every year on Mother’s Day she gave Michael a gift to celebrate him making her a mother.

“She was very ferocious in the way she loved you,” Michael said.

Amidst the grief of losing Mona, the family’s problems kept coming — this time, when Michael’s uncle was denied testing after leaving a hospital stay in mid-May and days later died. Joe Villegas’ death certificate lists COVID-19 as the primary cause.

He was taken by ambulance to Sharp Memorial Hospital in San Diego in May, following a fall. Next, he was transferred to the Kaiser Permanente hospital in Kearny Mesa. Before Kaiser discharged him, his wife asked that he be tested for COVID-19.

The couple’s daughter said her mom was told there weren’t enough tests.

So Villegas went home and had close contact with 10 family members over the Memorial Day weekend.

Because of his wife’s fears that he had the virus, Villegas got tested on May 26 at a drive-up CVS testing site. But that same day, his condition worsened — he was having symptoms of a potential brain bleed, his daughter said — and he went back to the Kaiser hospital. He stayed one night and was discharged even though test results had come back and showed he was positive.

“My mom literally asked, ‘What am I supposed to do? How do I fix this?’” said Vicki Villegas Sutherland, the couple’s daughter. “And there was no answer forthcoming.”

By June 2, her father was dead.

Joe, a grocery store manager whose careful financial planning allowed him to retire early and travel widely, died in his bedroom. His family peered through an open window, the granddaughters and extended family crying and laughing and talking with him on his last days. Inside the room were his caretaker, his wife and his daughter Vicki, who held his hands as he took his final breaths. The three of them tried to recreate a hospital-like setting, wearing PPE and masks. Caring for him required extremely close contact.

Both the caretaker and his wife contracted COVID-19.

Sutherland, a home health nurse, is thankful her dad was able to spend his last days at home but believes his death could have been avoided. The lack of testing caused her family much heartache, she said.

“The last two weeks of his life were just fraught,” she said. “I keep thinking, does it really have to be like that?”

In a statement, Kaiser acknowledged it may send some COVID-19 positive patients home if they have mild symptoms, to recover “in isolation from others with regular monitoring by clinicians via phone or other means.”

In a follow-up email, a spokesperson said Villegas was tested for COVID-19 during his stay at Sharp and transferred to Kaiser with presumed negative results. During his second hospital stay, Kaiser did test him for COVID-19, she said. She added that Villegas was discharged with instructions and a COVID-19 supply kit.

In initial prepared statements to inewsource given after his family granted permission allowing staff to talk, Kaiser incorrectly stated Villegas’ date of death and the Kaiser location where he was twice hospitalized. A spokesperson later acknowledged the mistake after an inquiry from inewsource.

Sharp spokesperson John Cihomsky did not comment on specifics of Villegas’ stay but said safety precautions were in place when he was hospitalized for his fall and that exposure to COVID-19 “for patients in that situation would be highly unlikely.”

Over email, he added: “Our practice now, and at that time, is to test any patient admitted to our hospital, whether they are symptomatic or asymptomatic.”

Death 97: ‘They were all just blindsided’

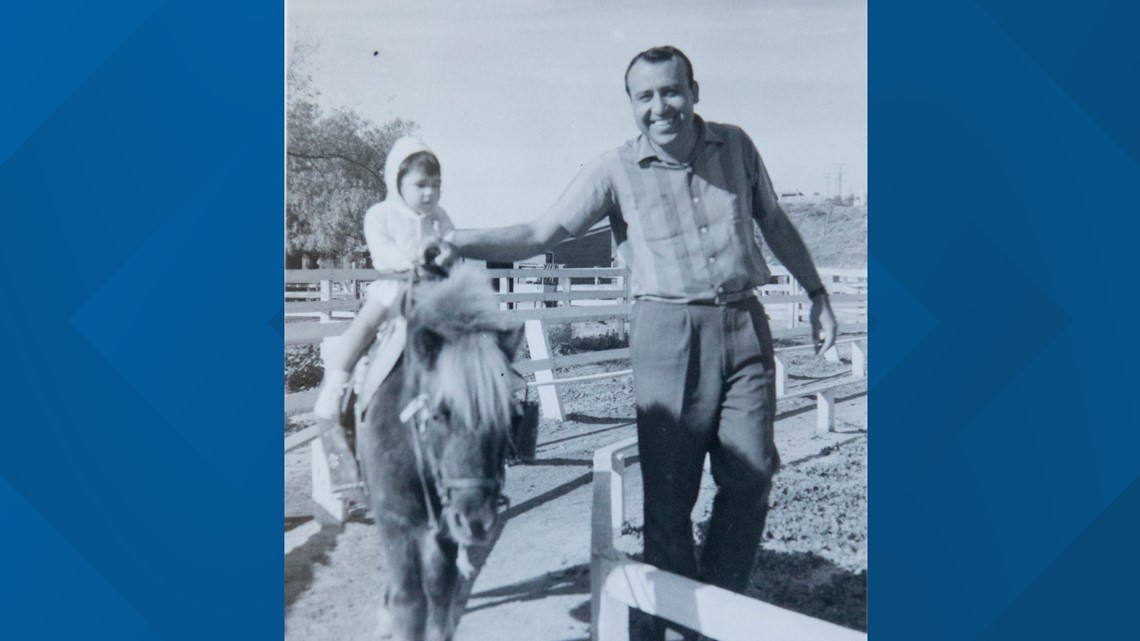

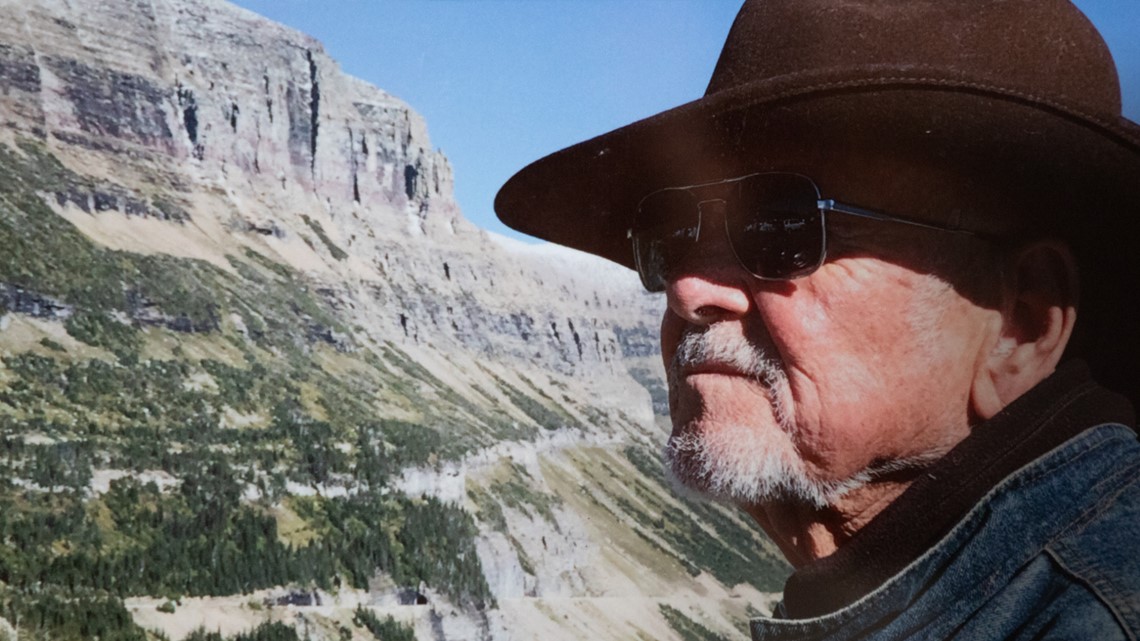

Lynn Charles Naibert had a suggestion for his daughter as she helped him settle into a San Diego assisted living and memory care home in January. How about she check in, too?

His worsening dementia meant he was up at night and at risk for wandering, his daughter, Pamela Reeb, 64, said. Stellar Care, a facility near El Cerrito where staff are described “like family” in one testimonial on its website, seemed like a way to keep him safe and improve the quality of his life.

A few months after moving, Naibert, 83, died of COVID-19 on April 20. Since the start of the pandemic, more than 40% of deaths nationwide have been residents of nursing homes and other long-term care facilities.

“The hardest thing for me to do was to take my father and put him into Stellar in January,” said his daughter Beverly Naibert, 62, who had cared for him in his home before he moved into Stellar Care, helped by a home health worker. “And then three months later, he's dead. How does that make me feel? I feel horrible. I should have just kept him home.”

Lynn Naibert’s children said the facility’s management didn’t let them know he was sick or dying until it was too late, didn’t test him for the virus, didn’t address his acute health issues before deciding he needed hospice care and has not answered their questions since his death.

On Monday, Beverly Naibert received some documents from Stellar Care, after requesting all of his files and information about the facility’s coronavirus infection and death count. The materials she received, she said, included no temperature readings from early March through April 3, and had no information about several incidents the family had been told about over the phone, including falls in his bedroom and in the hallway.

Reeb, who lives in Montana, said she got a series of phone calls in late March and early April saying her father fell a few times over a few days. And then suddenly, she was told they recommended he be put into hospice.

"And when she said 'hospice,' all the red lights started coming on. And I was like, I didn't quite understand why she would say that," Reeb said.

Lynn Naibert, a former teacher and perpetual quipster who raised a family with his wife, Penelope, on a sleepy Bay Park cul-de-sac, tested positive for the coronavirus at the UC San Diego hospital in La Jolla in early April and was admitted. He was allowed to see his son, Paul Naibert, who could offer little tenderness because of social distancing, but he took off his glove to hold his father’s hand before he died.

State records show 13 residents at Stellar Care have contracted the virus. Linda Cho, the facility’s executive director, declined to comment about the Naiberts’ concerns.

“Due to rules and regulations for our residents and families, it is not appropriate for us to respond at this time,” she wrote in an email.

Reeb thinks the facility’s management meant well but became overwhelmed.

“If you take one care facility and you multiply that by the thousands that are in California, I mean, they were all just blindsided by this thing,” she said.

Nguyen, the UCSD geriatrician, said the virus can manifest more stealthily in elderly patients, without a textbook presentation, running its course until the person ends up falling, becoming weak or dehydrated.

“It doesn't come with the usual signs that we think of — shortness of breath, cough, fever, (as) in others that have, essentially stronger immune systems. The whole idea is that we need to be more diligent in making sure we're closely following up with these older patients,” he said.

Nguyen added that loved ones and caregivers keeping a close watch on people with Alzheimer’s and other neurocognitive disorders can help detect illness. That wasn’t possible for Naibert, once the facility paused visits to mitigate the spread of the virus.

His daughter Beverly has wondered: Why was she, who was living alone and had been her father’s caretaker for years, deemed a greater risk to his health than the staff at Stellar Care?

In their final conversation, Lynn Naibert told Beverly he missed her.

“He wanted to come home,” she said. “We couldn't bring him home.”

A death that wasn’t counted

An unknown number of deaths of local residents with COVID-19 are not captured in the county’s official data.

Joseph Bondoc is one of them. He isn’t listed in the county data, even though he raised his family in National City and owned their home there for seven years before dying on May 21 while away at work in Massachusetts.

The county says it includes San Diego residents who die out of state in its coronavirus reports. A county spokesperson said because Bondoc died away from home there could be a lag in reporting from that state.

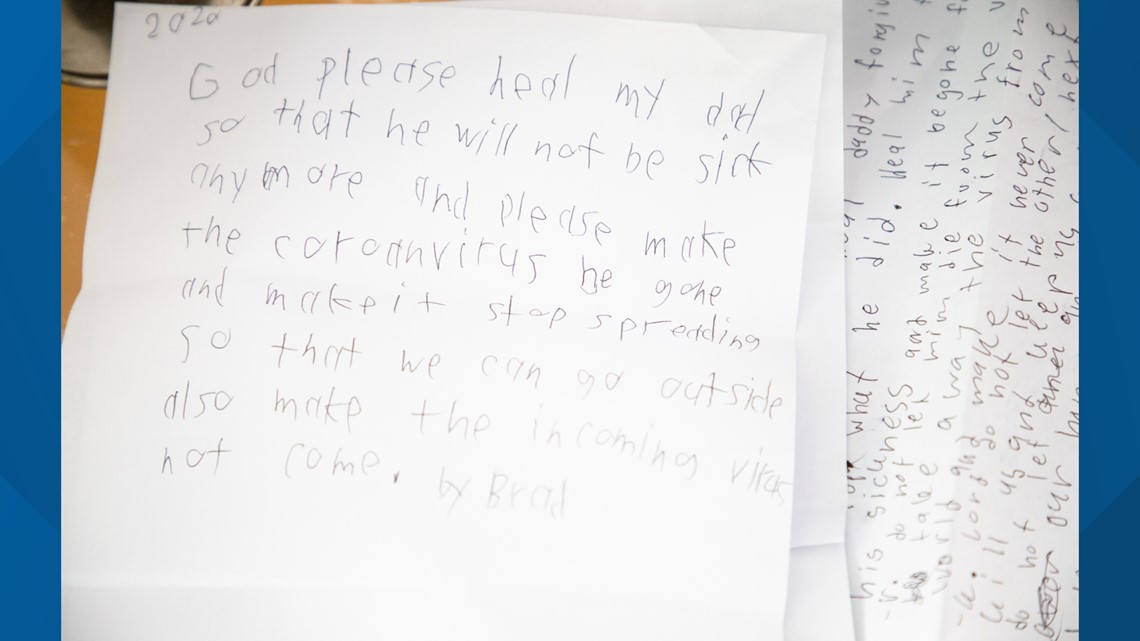

But Bondoc was counted by the military. He was among 24 of 47 crew members from a U.S Navy Military Sealift Command ship who tested positive, and the only one who died from the coronavirus. His death was the first of a civilian merchant mariner. The outbreak on the USNS Leroy Grumman — which was in dry dock in Boston and undergoing regularly scheduled maintenance — was among several the military struggled to contain as the pandemic took hold this spring.

Bondoc, who had retired from the Navy, left for Boston on March 24 in good health, aside from high blood pressure and cholesterol issues he’d been managing. He was in the middle of a vacation, sheltering in place at home in National City with his wife and three children.

When he left, his wife, Witchelda Bondoc, wondered why the Military Sealift Command was sending crews to Boston — then a hotspot for the virus — and whether he’d be safe. But her husband took precautions. He saw his doctor before he left, getting refills on his prescriptions and lab work done. He called his wife from aboard the plane as he departed, telling her everyone was wearing masks and social distancing.

About a month into his work assignment, he started feeling sick and developed a fever, so he got tested at a VA hospital. It was, as Witchelda had feared, positive. He was told to self-quarantine and placed under the care of the VA at the hotel where he and other crew members were staying.

A few days later, he left the hotel in an ambulance and was taken to Carney Hospital, a for-profit medical center in Boston that was partially converted to a coronavirus treatment facility.

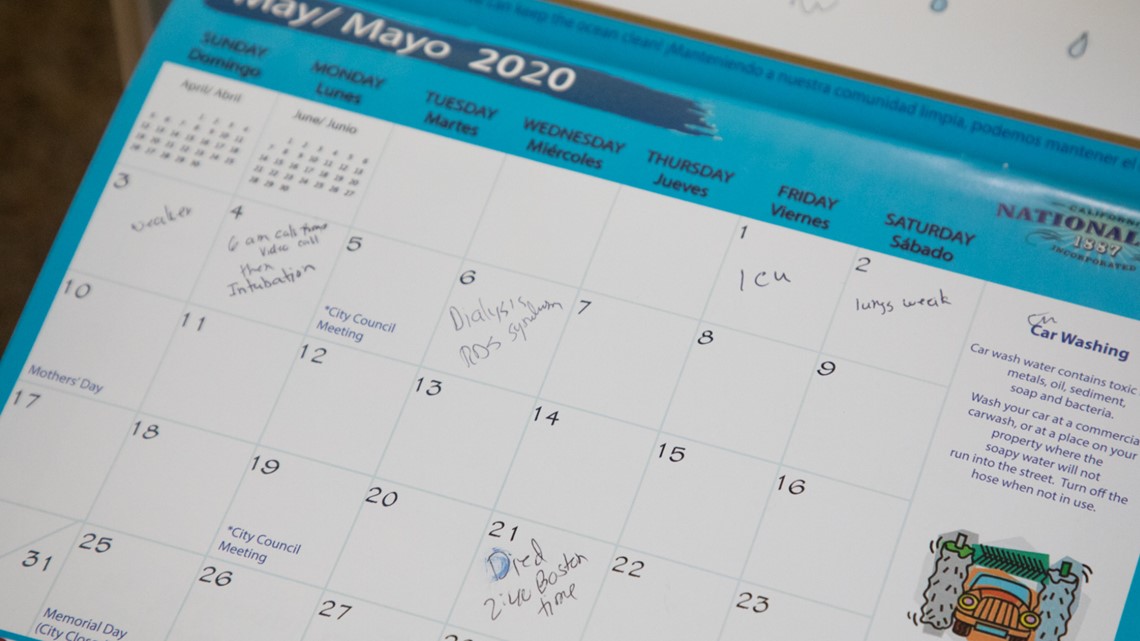

About 2,500 miles away, Witchelda stayed optimistic. She ordered her husband vitamins and asked her family in the Philippines to prepare special herbs to help him gain his strength when he got home. The couple talked frequently on FaceTime. Each day she handwrote notes on her husband’s health in her calendar: May 1, ICU; May 2, lungs weak; May 3, weaker.

They had a video call on May 4, and then Joseph was sedated and put on a ventilator. They wouldn’t speak again. Bondoc was buried at Miramar National Cemetery. A ceremony with military honors took place on June 30. It would have been his 55th birthday.

The Military Sealift Command declined inewsource’s interview request. In a statement, a spokesperson said the organization’s tactics to fight the virus evolved as they learned more, but repair work had to continue.

“While MSC executed its responsibility to protect the health of the MSC crews, there remained a continuing responsibility to maintain MSC ships to perform their national security missions,” the statement said.

It said Bondoc “was a long-time friend and co-worker to many” and “our heartfelt condolences are with his shipmates, family and friends.”

To his wife and children, he was the one always thinking about the future. He had planned to retire soon, his wife said.

Sitting under a small weathered American flag in the shade on her patio on a recent Friday, she teared up as she shared the words her 11-year-old daughter has been asking her:

“How are we going to live now?”

inewsource intern Natallie Rocha contributed to this report.