SAN DIEGO — The University of California has sued Dr. Kevin Murphy, the subject of a recent inewsource investigation, alleging fraud, concealment and misappropriation of a $10 million research gift meant to study an experimental brain treatment.

The day after the lawsuit was filed last week, Murphy sued the UC system. The former UC San Diego vice-chairman alleged whistleblower retaliation and named university higher-ups, including his former boss, as responsible for blocking his research efforts and punishing him for filing complaints about what happened.

Both suits corroborate inewsource’s reporting and offer previously undisclosed details about the conflict inside UCSD.

Murphy did not respond to repeated requests for comment on this story. His lawyer in the case against the university, Mark Quigley of Greene Broillet & Wheeler, declined to speak about the ongoing lawsuit. UCSD also declined to comment.

The legal battle in San Diego Superior Court is the latest chapter in a yearslong UC investigation into allegations that Murphy used money from a $10 million research donation to enrich himself and his private businesses. inewsource’s original reporting was the first public account of how one of the largest-ever donations for a UCSD employee’s research was wasted at one of America’s premier research universities.

The doctor’s actions, according to the UC suit, were done with “malice, fraud, oppression, and reckless disregard,” and the university system is seeking restitution, damages and civil penalties from Murphy and his private companies, as well as a trial by jury.

In July, UCSD provided inewsource with a summary of its investigative findings but would not grant an interview or answer most of our questions.

Murphy’s lawsuit claims UCSD released those false findings to damage his reputation.

He also alleges UCSD misappropriated donor funds in violation of university policy and state and federal laws. The university’s conduct was “economically wasteful,” the lawsuit said, and involved “gross misconduct.”

The missing pieces

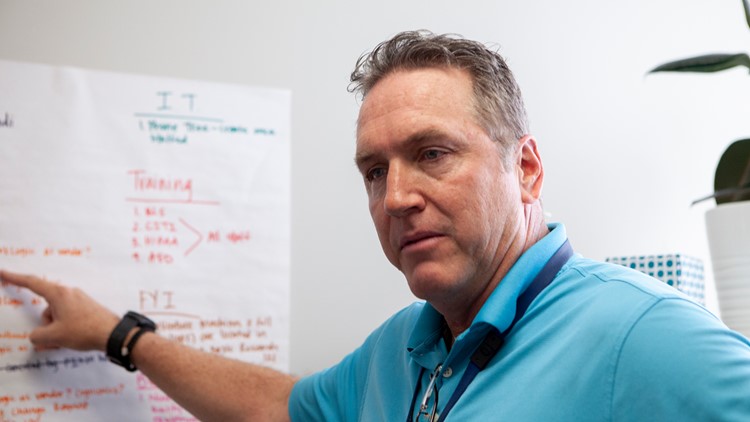

Murphy specialized in cancer care as a faculty member since 2005 of UCSD’s Department of Radiation Medicine and Applied Sciences.

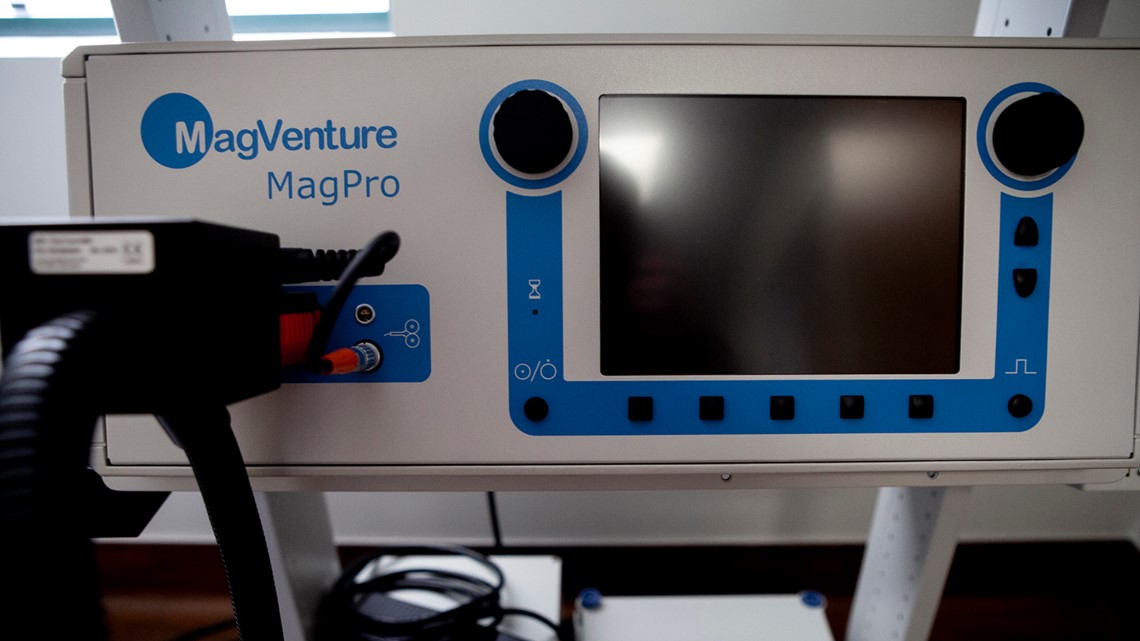

In 2013, he stumbled across transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS — a proven therapy that sends electromagnetic pulses into the brain to treat depression, anxiety, chronic pain, and other mental and physical disorders.

Over the next few years, Murphy said he developed his own version of TMS that improved upon the standard treatment by “personalizing” it. His software adjusts the frequency and intensity of the electromagnetic pulses to fine-tune a patient’s brainwaves.

He calls his version PrTMS and has repeatedly said in interviews and on his website that it can treat a wide range of mental and physical health problems — as well as a bad golf swing — but he has not completed any clinical trials to support those claims.

inewsource’s REWIRED investigation recounted the experience of a former Navy SEAL who had a psychotic episode after Murphy oversaw at least 234 of the veteran’s brain stimulation treatments. Murphy denied responsibility for the psychosis and told inewsource he attributed it to the veteran — John Surmont — being homeless, manic and on drugs. Yet reporters found Murphy’s claims about his patient were false.

During Surmont’s treatments, Murphy said he also used his technique to treat local philanthropist Charles Kreutzkamp for chemobrain, a disorder caused by chemotherapy that can result in thinking and memory problems.

After he died, Kreutzkamp’s family trust donated $10 million to the university “for cancer research” but didn’t go into detail. Months later, a letter signed by his widow clarified the donation was meant for Murphy to run five clinical trials on the efficacy of his software. She stated that the family donated the money because of how successful Murphy’s treatment was for her late husband.

Four years later, the UC lawsuit claims "a significant portion" of the $6.9 million spent so far has been used to personally benefit Murphy and his private businesses, which include The Medical Synchrony Research Institute, The Medical Synchrony Center (later called Mindset), FreqLogic, PeakLogic and PeakMD Institute.

The lawsuit breaks down the many ways Murphy allegedly misspent the funds: selling UCSD’s equipment without permission, invoicing the university for items used by his private companies and hiring his business associate to work at the university.

UCSD conducted two audits to track down how Kreutzkamp’s gift was spent, the lawsuit says.

The first, in late 2018, found 52 missing pieces of equipment worth about $334,000. A year later, the second audit found some equipment was returned, but 28 items worth about $158,000 were still missing.

During the audits, the lawsuit says, UCSD discovered that Murphy had billed the school for almost $68,000 worth of equipment that he then sold to Windmill Wellness Ranch, a private clinic in Texas. The clinic partnered with Murphy’s company to provide his brain treatments.

Murphy did not tell UCSD about the sale and kept the money, the UC system alleges.

In total, Murphy and his businesses made at least $122,000 selling university equipment without permission, according to the lawsuit.

In previous interviews with inewsource and in a statement made to the university under penalty of perjury, Murphy denied using any university resources for personal gain. His lawsuit against the UC regents says all the missing equipment has been accounted for by university employees.

Murphy’s former business partner who helped with his recordkeeping, Diana Shapiro, has said the same in past interviews with inewsource.

The UC lawsuit says Shapiro was paid approximately $143,000 from the Kruetzkamp donation to help Murphy with research but spent her time at UCSD supporting Murphy’s private endeavors. It also alleges the doctor told Shapiro to invoice the university for equipment that was shipped to his private clinic, not his UCSD research lab, and that he used the equipment for his private businesses.

Murphy also instructed other UCSD employees to do work for his private businesses, the lawsuit says.

In an email to inewsource, Shapiro said the “false and misleading allegations concerning me will be disproven,” and declined to comment further.

Shapiro eventually became chief financial officer of PeakLogic, the company Murphy founded to oversee the development of his software, and she helped expand the number of clinics using PrTMS around the country.

She left that job in June, according to her LinkedIn profile, and is now working as a managing partner for a consulting firm called Eco Tech Ventures.

Risky businesses

UC employees must get permission before founding companies or developing potentially patentable technology — and in many cases, the institution is entitled to some of the earnings that come from them.

Murphy helped establish at least five private businesses to support his personalized TMS software and treatment. The university system alleges he did not get prior approval and provided false paperwork to UCSD about them.

According to the UC lawsuit, Murphy’s annual filings with the university stated he spent much less time working for his private businesses and earned far less money from them than he actually did. Plus, Murphy failed to get approval to treat patients at his private clinics as required and didn’t report that income either.

That money belonged to UCSD, the university argues.

To support the point, the lawsuit describes how Murphy disclosed that income only after the school began its investigation into him by asking for “prior approval” to establish two of his companies in mid-2018. That request was made more than a year after they were founded and came a couple of months after an employee in Murphy’s department filed a whistleblower complaint against him.

Then, in a “supplemental memo,” the lawsuit claims, Murphy disclosed he had earned income from those companies, unlike what he had previously reported.

The UC Board of Regents claims Murphy knowingly committed these acts.

While the lawsuit covered a wide range of allegations against the doctor, it did not mention some of what inewsource uncovered in its previous reporting, including the veteran’s psychotic break, apparent academic plagiarism in one of Murphy’s research proposals and the role of Michael McDermott, a former top UCSD lawyer.

McDermott assisted Murphy while the doctor established his PrTMS companies and started up clinical trials at the university. The lawyer was listed as an officer in two of Murphy’s businesses while also serving as the UCSD health system’s chief counsel.

In prior interviews with inewsource, Murphy repeatedly cited McDermott as the reason he believed he had university approval for his actions. McDermott declined a request for an interview.

UCSD spokesperson Kim Kennedy said the university could not comment while its internal inquiry was ongoing, but she promised a sit-down interview once it was complete.

After providing a summary of its investigative findings, UCSD declined to honor its agreement or answer questions from reporters.

The doctor’s position

Murphy’s lawsuit casts a different image of what transpired at UCSD over the past four years.

The doctor claims his research efforts were stalled by administrators who wanted to use the $10 million donation for their own purposes, even though it was intended for his clinical trials. He says Dr. Scott Lippman, the director of the Moores Cancer Center, tried to earmark the funds for the center and only intended to leave a small fraction of the money for Murphy.

When the doctor insisted on using the funds for his research, he claims he was bullied, harassed and threatened.

Murphy filed a whistleblower retaliation complaint in December 2018 about the incidents and followed up with four supplementary reports over the next two years, his lawsuit says.

In January, Murphy provided inewsource with the response he received from the UC Board of Regents to one of his early complaints, which asked the doctor to clarify his concerns. Murphy’s lawsuit claims none of his whistleblower reports were ever investigated.

In response to his complaints, the doctor says UCSD retaliated against him by terminating his employment and intentionally “leaking false information” to the news media.

Murphy also alleges his former boss, department chair Dr. Arno Mundt, convinced him to move to a part-time contractor position in bad faith, claiming it would help clear up any potential conflicts that were holding up Murphy’s research.

Emails Murphy gave inewsource show multiple higher-ups told the doctor that stepping down would help his research efforts. For example, the associate vice chancellor for academic affairs told Murphy in late 2018 the transition “would alleviate the conflict of commitment issues,” and Mundt told him it “will be helpful in getting your trials going again.”

Murphy’s lawsuit says that after the doctor moved into a contractor role, Mundt implied to other employees Murphy was being punished for wrongdoing and spread rumors that he was “poisoning the well” in the department.

In mid-2020, the doctor’s contract was not renewed, ending his 16-year career with UCSD. None of his trials were ever conducted.

Murphy’s list of allegations against his boss is long. The doctor claims Mundt conducted none of his annual reviews for the past three years, didn’t give him students to teach and then didn’t promote him because he hadn’t done enough teaching.

Plus, Murphy claims, Mundt cut him out of the cardiac radiosurgery program he had helped build over the past 13 years, put a junior faculty member in his place and offered the doctor’s position at a cancer clinic to someone else.

Mundt did not respond to requests to comment for this story.

Conferences on the lawsuits are scheduled for mid-2021, and trial dates have not been set.