SAN DIEGO — Right off the coast of La Jolla Shores, the Scripps Pier holds the answer to many mysteries. Research projects and data gathering by some of the world's brightest, most curious, and ocean-conscious minds. One of the projects includes several cages along the pier, placed underwater, to test materials from polyester to bamboo to see how they degrade in the ocean.

Dr. Dimitri Deheyn, marine biologist and leader of the Deheyn Lab at Scripps Institution of Oceanography says, "we leave them [cages] out for months and months." And they test for microfibers. Microfibers are small microscopic plastic particles and we have released trillions of them. Another fellow researcher and oceanographer Dr. Sarah-Jeanne Royer says, "we have all these indivisible fibers that are flying out into the atmosphere."

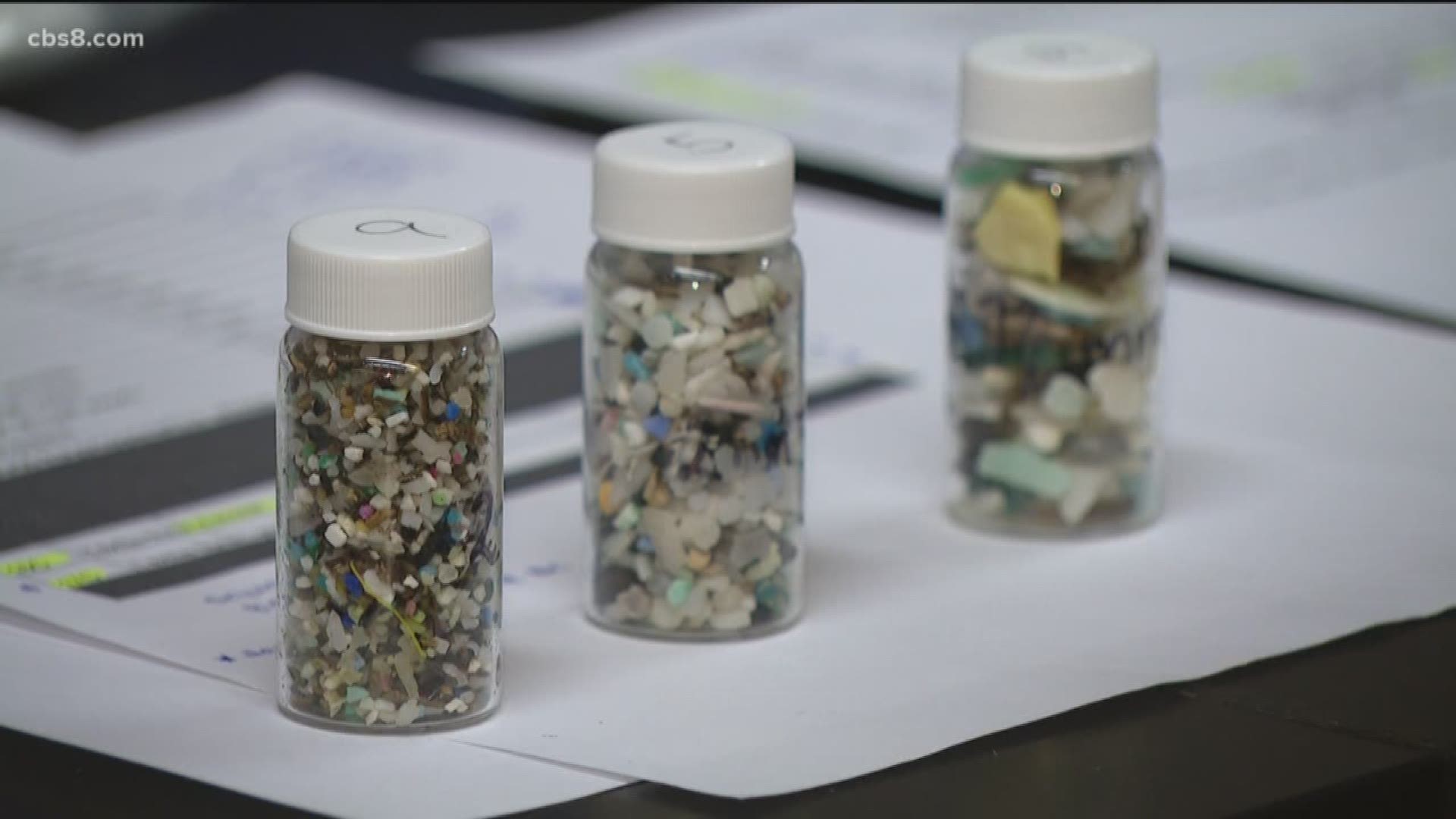

The microfibers are much smaller than microplastics, and they show up across the air, land, and water, and in all of us. The number of microfibers are being researched, but scientists have released stats on microplastics. A new study in the Journal Environmental Science and Technology states it's possible we consume up to 52,000 microplastics a year. And, humans may be inhaling an astonishing 74,000 microplastics. So researchers say, they can only imagine how many microfibers there would be. It's a new concept being researched in the Deheyn Lab that reveals more about the day-to-day damage plastics and other synthetic materials are doing to the planet and our bodies.

Dr. Deheyn says, "there's a lot of effort to test impact for public health impact." Researchers hope that if some people aren't as concerned about the planet, maybe they'll take action knowing their health is also at risk. "The very vicious plastic is the invisible one, the one you can't see but we breathe, we drink, we eat," Deheyn said.

So where do these microfibers come from? It comes from something we use every single day - our clothes, specifically clothes made of synthetics like polyester, nylon, and spandex. "What you and I wear are the main source of these fibers. It's very sad the industry has pushed these materials to be so essential to us," Deheyn said.

Rubbing and washing our clothes releases microfibers. In fact, they're found in abundance in laundry water, "cleaning up the microfibers is impossible, it's just not possible. They're too small," says Deheyn.

So the best way is to lighten our load by using natural materials, "let's go back to hemp, back to cotton. Let's go back to natural fibers."