MONTGOMERY, Ala. (AP) — When deadly twisters chewed through the South and Midwest in 2011, thousands of people in the killers' paths had nowhere to hide. Now many of those families are taking an unusual extra step to be ready next time: adding tornado shelters to their homes.

A year after the storms, sales of small residential shelters known as safe rooms are surging across much of the nation, especially in hard-hit communities such as Montgomery and Tuscaloosa in Alabama and in Joplin, Mo., where twisters laid waste to entire neighborhoods.

Manufacturers can barely keep up with demand, and some states are offering grants and other financial incentives to help pay for the added protection and peace of mind.

Tom Cook didn't need convincing. When a 2008 tornado barreled toward his home in rural southwest Missouri, Cook, his wife and their teenage daughter sought refuge in a bathroom. It wasn't enough. His wife was killed.

Cook moved to nearby Joplin to rebuild, never imaging he would confront another monster twister. But he had a safe room installed in the garage just in case.

On May 22, Cook and his daughter huddled inside the small steel enclosure while an EF-5 tornado roared outside. They emerged unharmed, although the new house was gone.

"It was blown away completely — again," he said. "The only thing standing was that storm room."

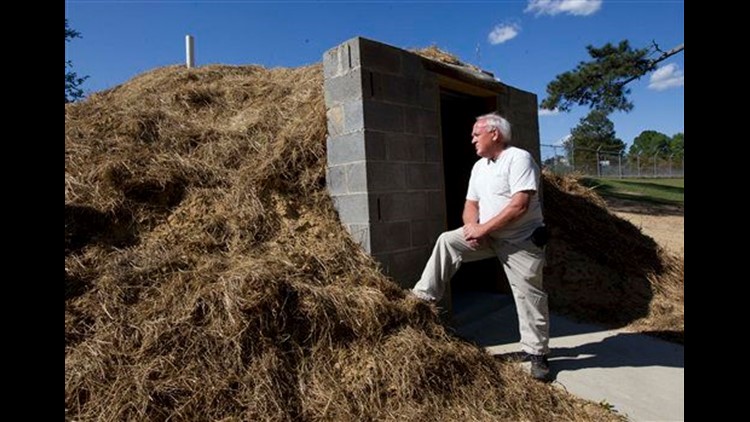

Generations ago, homes across America's Tornado Alley often came equipped with storm cellars, usually a small concrete bunker buried in the backyard. Although some of those remain, they are largely relics of a bygone era. And basements are less common than they used to be, leaving many people with no refuge except maybe a bathtub or a room deep inside the house.

The renewed interest in shelters was stirred by last year's staggering death toll — 358 killed in the South and 161 dead in Joplin. So far this year, more than 60 people have perished in U.S. twisters.

Safe rooms feature thick steel walls and doors that can withstand winds up to 250 mph. They are typically windowless, with no light fixtures and no electricity — just a small, reinforced place to ride out the storm. Costs generally range from $3,500 to $6,000.

Sizes vary, but most hold only a few people. They can be bolted to the floor of a garage or custom-fitted to squeeze into a small space, even a closet. Some are so small occupants have to crawl inside. A few are buried in the yard like the old storm shelters of the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Before the twister devastated Joplin, the Neosho, Mo., safe room manufacturer called Twister Safe had four employees. Now it has 20.

"Business has probably quadrupled, at least," owner Enos Davis said. "We're selling 400 to 500 a year now, compared to maybe 100 before."

Twister Safe's spike in business is even more impressive in Missouri, which does not offer grant money for safe rooms, opting to use its share of federal disaster money for community shelters.

Missouri's choice spotlights a debate in states seeking better tornado protection: Is disaster aid better spent on safe rooms in individual homes or on larger public shelters designed to protect hundreds or thousands of people?

The downside of public shelters is getting there. Even with improvements in twister prediction, venturing out into a rapidly brewing storm is perilous.

"I wouldn't get my family into a car and run that risk," Joplin Assistant City Manager Sam Anselm said. "If you have the opportunity to put something in your house, that's what we would encourage folks to do."

In January, more than 50 people sought safety in a dome-shaped public shelter as a tornado ripped through Maplesville, Ala. No one was hurt.

"The shelter did what it was supposed to do," Mayor Aubrey Latham said.

Since 2005, 31 community shelters have been built in Missouri using FEMA funds, and nine others are under construction, according to Mike O'Connell of the Missouri State Emergency Management Agency.

That number is about to grow. Joplin voters earlier this month approved a $62 million bond issue that will be combined with insurance money and federal aid to build storm shelters at every school. The shelters will double as gyms, classrooms or kitchens.

After more than five dozen tornadoes struck Alabama on April 27, 2011, FEMA gave the state $17 million for safe rooms. More than 4,300 people filed applications for grants. Of those, nearly half have been approved. The others are still being reviewed.

"They absolutely save lives," said Art Faulkner, director of the Alabama Emergency Management Agency.

Alabama is also using $49 million in FEMA money for community shelters.

Following the 2011 tornadoes, nearly 6,200 applications were submitted to Mississippi's "A Safe Place to Go" program, which also uses FEMA funds. That was more requests than the program's $8 million could fund.

Among those who received money were Renee and Larry Seales of Smithville, Miss., where 16 people died in a 2011 twister, including both of Renee's parents. They built a dome-shaped bunker buried in their yard.

"I don't know how many have been put in Smithville, but it seems like every house has one," Renee Seales said.

Since 2009, nearly 16,000 people in Arkansas have received rebates of up to $1,000 to add residential safe rooms.

In Joplin, the state's preference for community shelters leaves residents to pay for safe rooms out of pocket. But for many, the cost is well worth it.

Last May, Debbie and Darrell Nichols hunched inside their safe room in the garage as soon as the tornado sirens began blaring. The roof of their neighbor's home came crashing through their kitchen, and it probably would have killed them. Inside the reinforced room, they were unhurt.

"We were holding hands and holding onto each other," Debbie Nichols said. "Then you hear the glass breaking and the roar, and your ears begin to pop. We walked out, and it was like a scene from 'The Wizard of Oz.'"

Betty Harryman was in a Joplin hospital about to have open-heart surgery when the twister hit. Her bad heart probably saved her life: Her home was leveled.

So when Harryman rebuilt, she added a small safe room where she keeps bottled water and a battery-operated light, fan and radio.

"After what happened," she said, "we thought it would be stupid not to have a safe room."

___

Mohr reported from Smithville and Jackson, Miss. Salter reported from St. Louis.

Copyright 2012 The Associated Press.