“I don't think they do a good investigation on a gay murder. They think, ‘Oh, that is one more gone.’ When you gay, it takes forever.” — Marsha P. Johnson.

Those who knew Marsha P. Johnson remember her determination.

“She was the Rosa Parks of the LGBTQ movement,” transgender activist Mariah Lopez told InsideEdition.com.

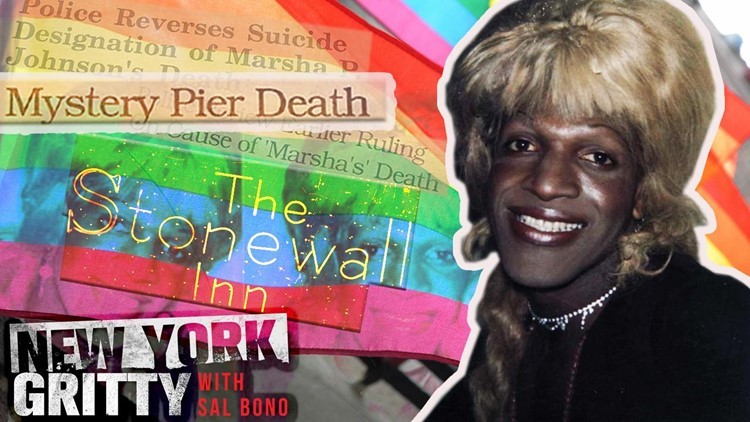

A transgender woman and drag queen, Johnson, born Malcolm Michaels Jr. in Elizabeth, New Jersey, is known for throwing “the shot glass heard around the world,” according to historian David Carter, author of the book, “Stonewall.”

In the early hours of June 28, 1969, Johnson, as the legend goes, hurled the drinking glass into a mirror at the Stonewall Inn, a gay club in New York City’s Greenwich Village, amid a police raid, kicking off the Stonewall riots, a series of violent demonstrations between cops and gay rights activists.

“When she shattered the mirror, she must have scared the s*** out of the police,” said Lopez.

But while the big moment looms large in Marsha lore, her friends say it’s the quieter moments that defined her.

“Marsha was fun. She made us laugh, that was the important thing,” Tree, the longtime bartender at the Stonewall Inn, who asked that his last name not be used, told InsideEdition.com.

“She cared about the community and making a change,” former Village Voice columnist and NewNowNext columnist Michael Musto said of Johnson, with whom he was friendly. “She wasn't a party girl. She was in bars a lot, but that was part of her being part of the community.”

That community was rattled in July 1992, when, shortly after that year’s pride parade, Johnson’s body was found floating in the Hudson River near the Christopher Street Pier. She was 46 years old.

How she got there, though, is a mystery that may never be answered to the satisfaction of those who cared for her.

‘She Didn’t Leave a Note’

Days before she was found in the river, Johnson was captured pondering death on home video footage provided to InsideEdition.com by Victoria Cruz, an LGBTQ activist who worked for the New York Anti-Violence Project and has fought to make sure Johnson is not forgotten.

“I don't think they do a good investigation on a gay murder. They think, ‘Oh, that is one more gone.’ When you gay, it takes forever,” Johnson says in the video. “I always say tomorrow is not promised to me.”

Friends say Johnson was acting normally when they last saw her around Greenwich Village on July 4, 1992, but two days later her body was found floating in the Hudson River. Cruz says people told her Johnson was being chased the night she disappeared, although authorities have not commented on this.

When her body was found, police quickly ruled the death a suicide, something that outraged many of those who knew her and said she never would have taken her own life.

“She wasn't suicidal,” said Musto. “She did face mental challenges, but she was not in a suicidal mood at this time.”

Many point to the fact that Johnson was found with a bruise on the back of her head as evidence that she might have been attacked.

“She couldn't have self-inflicted that, very hard to do that,” said Musto.

That theory was called into question in the 2017 documentary “The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson,” however, when a former medical examiner not affiliated with Johnson’s case concluded that the bruise could have come from her body decomposing in the water for a couple days.

Randy Wicker, Johnson’s roommate at the time of her death, recalled seeing where her body had been placed after it was pulled from the river.

“As she laid there, her blood soaked into the pavement,” Wicker said. “There was Marsha's blood and everything, where her body had lain on the asphalt.” It was there a makeshift memorial sprung up to Johnson, flowers dotting the ground.

Her body was cremated and the ashes were spread in the Hudson River off the Christopher Street Pier.

For months afterward, activists pushed for a more thorough investigation. In December, five months after her body was found, the outpouring reached fever pitch. Among the voices was Tom Duane, then a city council member. Duane, who was also the first openly gay New York state senator with HIV, demanded justice for Johnson, meeting with investigators in an effort to convince them to reopen the case.

“Her death deserved the most exhaustive investigation,” Duane told InsideEdition.com, adding that the case “was also unusual because it was a very rapid determination.”

Her death was changed from “suicide” to “undetermined” after the public pressure mounted on authorities.

“We were strong in our position that there needed to be more investigative work because even if Marsha was not world-famous, she was important to the LGBTQ community and the downtown community,” Duane continued. “Usually when there is a death by suicide the person usually leaves a note.

“... She didn’t leave a note.”

Loud and Proud

While many were hiding their sexuality, Johnson was loud and proud of who she was. A drag performer and transgender pioneer, she took her name from a Howard Johnson’s near Washington Square Park where she would hang out. She also called herself “Black Marsha,” before combining the names. The "P" in her name stood for “pay it no mind,” meaning she didn’t pay attention to anyone who didn’t agree with her lifestyle.

“In the '60s we had to live in the shadows and hide. The great thing about Marsha P. Johnson is she never subscribed to that. She never lived in any shadow. She was just there and you had to deal with it,” Musto said.

Musto remembers Johnson as someone “who marched to her own drum.” She had flowers in her hair and would wear trash bags as dresses.

Johnson was a bridge within the queer community, which was no stranger to discrimination within its own walls.

“There's always been discrimination within the queer community,” said Musto. “And in the ‘60s especially a lot of the white gay men looked down on people of color. The gay males sometimes looked down on drag and trans.”

The Stonewall Inn, where it’s said Johnson made her stand, initially served as a haven for gay men and lesbians; trans people and drag queens were not allowed in.

But Johnson, with her larger than life personality, ended up being one of the first trans people inside. “She was ahead of her time,” said Cruz.

When trans people and drag queens were pushed to the back of the very first pride parade, Johnson and her fellow trans activist, Sylvia Rivera, pushed their way forward.

“Marsha and Sylvia … were told not to march in the gay pride parade because the gays didn't want drag queens,” Musto said.

The two found support in each other. “There was a love affair of activism, there was a love affair of wanting to do for the community that had not been done before,” Cruz said.

Together, Johnson and Rivera founded Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, or STAR, which was based out of Greenwich Village, to help young gay and transgender people in the city find shelter, food and a community.

Amid it all, Johnson earned money as a sex worker, a dangerous profession in ‘70s New York. During one encounter, she was even shot, Wicker said. When she went to the hospital, doctors told her the bullet was so close to her spine that she would be paralyzed if they removed it. Johnson spent the rest of her life suffering from immense back pain thanks to the round lodged in her.

“She never complained,” said Wicker. “... You could see these little shivers of pain. But she never said, ‘Oh, my back!’ She just went on living life.”

As the AIDS epidemic picked up steam, Johnson, who was herself HIV-positive, became a prominent activist with the AIDS Coalition and would protest the high cost of drugs to help treat the disease known then on the street as “gay cancer.”

Those who believe Johnson took her own life point to her medical history as a basis for their argument. The pain became unbearable, they say, the HIV diagnosis daunting.

“Of course she had pains from the bullet in her back,” Cruz said. “Of course she had HIV. You know, all this affects the psyche of a person. But at the same time ... will she commit suicide? But why?”

Before Johnson died, she had a “mental breakdown,” according to Wicker, inside their apartment in Hoboken, New Jersey, which overlooks Greenwich Village from the other side of the Hudson.

Wicker said she was taken to a mental hospital after she had trashed his apartment by spray-painting the kitchen with silver paint and breaking his crystalware, as well as hurling groceries at buses in Greenwich Village.

Old Wounds

It was 20 years before police reopened Johnson’s death for a second look in 2012. In the intervening years, speculation ran rampant, the uncertainty fueling wild conjecture. Maybe Johnson was killed in a mafia hit, some said. Maybe she tripped and fell into the river as she was heckled, wondered others. She could even have slipped between the boards of the then-dilapidated pier on a late-night stroll.

“‘I think she was murdered. I think some straight guys dumped her in the Hudson.’ That's the rumor we heard,” Tree, the Stonewall Inn bartender, said.

Wicker said that before she went missing on the night of July 6, 1992, Johnson said she was being harassed by people making fun of how she dressed.

“I think it's probably a 55 [percent] that she was [murdered], and a 45 [percent] that she wasn't [murdered],” Wicker said. “She could've walked down to that area, and somebody starts harassing her again. Or somebody even on drugs is going after her and she either gets pushed in the water, stumbles into the water.”

But the New York Police Department maintains there is not enough evidence to indicate foul play in the case, which they closed again in 2013 after changing Johnson’s manner of death from “suicide” to “undetermined.”

“NYPD detectives conducted a thorough and exhaustive investigation into this cold case,” a police spokesperson told InsideEdition.com in a statement on Johnson’s death. “The NYPD Cold Case Squad looked into the case in 2012. The cause of death was changed from Cause of Death: Drowning / Manner of Death: Suicide to Cause of death: Drowning / Manner of Death: Undetermined.

“The case is now closed,” the statement concludes.

But for Cruz and Wicker, that’s not enough. They continue to press for more to be done.

“What I conclude about her death that probably … she was probably running for her life,” said Cruz. “The piers at the time were dilapidated, holes and everything else.

“... She might have stepped on a piece of board or wood that was ready just to fall and she fell in,” she continued.

But that, said Cruz, “constitutes murder also.”

Closure, however, may never come.

Legacy

“I am very fortunate to be black, gay and transvestite to get as far as I did in this world,” Johnson professes in the home video taken just days before her death.

While there is still a long way to go, there have been massive strides since Johnson and Rivera fought their way to the front of the pride parade.

“Their legacy is that everything trans came out of their movement [because] there wasn’t a trans movement, [Johnson and Rivera] pushed the trans movement,” Lopez, the transgender activist, said. “The fact that transgender became ever present in American psyche is their legacy.”

While the initial run of STAR, the group started by Johnson and Rivera, lasted just three years, it was later reformed in the early 2000s by Rivera and Lopez. Rivera passed away in 2002.

“I am carrying on the legacy started by two homeless trans people. It is a group of trans activist who do the work and answer the phones in a grassroots way. We help those in hospitals and in prison,” Lopez said of STAR today. “Sylvia and Marsha couldn’t envision the world we live in today and STAR cannot die.”

In the years since Johnson’s death, New York City has undergone drastic changes. The grittiness of Johnson’s Greenwich Village is gone, replaced by posh restaurants, expensive bars and high-rise apartments. The pier where Johnson’s body was laid out has been repaired.

Gay bars are now open to all who want to come. “Stonewall was the turning point for the queer community,” Musto said. “After that, it wasn't really an overnight dramatic effect, but still you could tell that gay people and queer people were not hiding in the shadows as much.”

In 2016, President Obama declared the Stonewall Inn a National and Historic Landmark. If Johnson had lived to hear the news, “she'd say, ‘One of my people did the right thing,’” Tree said.

A photo of Johnson and Rivera now hangs in the back room of the Stonewall Inn as a tribute to the two. This year marks 50 years since the Stonewall riots.

“Marsha left behind a legacy that people could be themselves,” said Tree. “You see it now. People go out anyway. Drag queens that are performing in clubs just jumping cabs, take trains, but she is the beginning.

“[Stonewall] is Mecca for the gay community,” he added. “[Johnson] is like one of the angels.”

Duane said it’s vital to keep up the fight that Johnson started. “The fight for social justice and civil rights has not been won and can be taken away very quickly,” Duane said. “Yes, we have made progress, but don’t give up the fight. It is important to keep Marsha’s name alive.”

"She gave you the shirt off her back,” added Cruz. “If she received a check on Friday, by Sunday she had no money because she was giving it away buying people food, helping.

“Help one another…. We need to be Marsha P. Johnson all the time."

RELATED STORIES