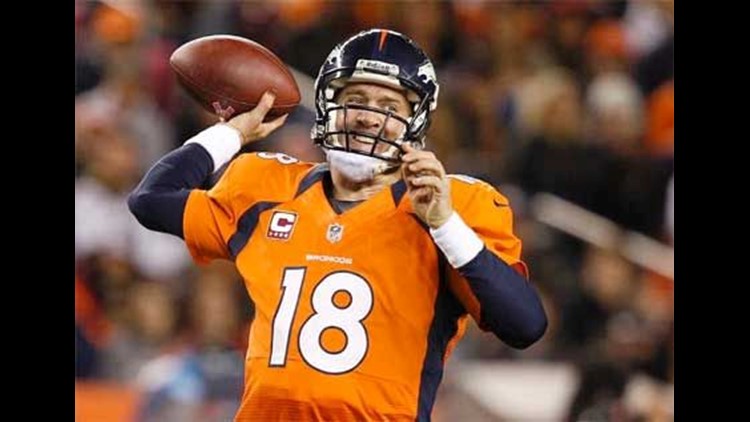

On Peyton Manning's first drive of his first game as a visiting player in Indianapolis, the Denver Broncos faced third down and 1 yard to go. Manning handed the football to Knowshon Moreno, who was stopped short. Denver punted.

On Manning's third drive, again he faced third-and-1, again he gave the ball to Moreno, and again the play was stuffed. Again, Denver punted.

"Hit a little rut there," Manning said hours later, after the Colts gave his Broncos their first loss of the season.

Other NFL offenses failed on similar plays Sunday, and it happens week after week: In the most critical of short-yardage situations, teams are converting at the lowest rate since at least 1995. The days of smash-mouth football, of bruising backs pushing piles forward with the help of run-blocking offensive linemen, are gone. Teams that have perfected the pass are not as equipped as they used to be for getting a key yard — or even inches — on the ground.

"The concept of running the football," former NFL coach Marty Schottenheimer said, "has kind of taken a back seat."

One of his 1980s Browns teams had two 1,000-yard rushers in the same season. One of his 1990s Chiefs clubs led the league in yards rushing. His tenure with the Chargers in the early 2000s featured LaDainian Tomlinson.

Times have changed.

"People have decided that the best, most efficient, way to go about it is to go ahead and spread the field out and try to get the quarterback a chance to do a pre-snap read," Schottenheimer said. "And essentially, the play is called after the quarterback has stood there and looked at the defense and its deployment and figured out where to throw."

Increasingly, teams can't gain what they want on the ground on third or fourth down with 2 or fewer yards needed for a first down or a touchdown. And increasingly, they're passing on those plays.

In all of those situations — third-and-2-or-less, fourth-and-2-or-less, including goal-to-go — NFL teams were successful 58.5 percent of the time through games of Oct. 14, according to STATS. That is a lower rate on such plays than for any full season since 1995 (that's how far STATS data goes back).

The rate in 1995 was 65.1 percent. In 2008, it was 63.7, and has been declining steadily since.

"My only answer," Steelers defensive coordinator Dick LeBeau said, "would be they don't quite run as much as they used to."

That, of course, is true. Games this season are averaging 53.2 running attempts, the fewest in the Super Bowl era, and 213.7 yards rushing, the third-fewest. Passing, meanwhile, is on pace for records of 72.3 throws and 489.2 net yards passing per game.

In 1987, for example, offenses were far more balanced, with 62.8 runs and 64.2 passes per game.

"We're more of a throwing league. ... Whatever you do more, you're likely to get a little better at," LeBeau said.

Plus, he noted, "It's easier to throw the ball over somebody's head for 40 yards than it is to pound down the field 3 at a time."

Dan Reeves, who coached in four Super Bowls, pointed out various rules changes that promoted passing, from restrictions on defensive backs to reductions on practicing in pads.

"Blocking and tackling are fundamentals you can't teach without pads," Reeves said, "but one of the things you can do is work on timing in the passing game."

In short-yardage situations, teams pass more than they used to: This season, the breakdown is about 55 percent runs, 45 percent passes on third- or fourth-and-short. Back in 1995, it was 63 percent runs, 37 percent passes, STATS said.

In 1995, the success rates on those runs was 71 percent. It dropped a bit below 66 percent the past two seasons, meaning teams are failing about one out of every three tries.

Take a look at Sunday. At the end of the second quarter against the Jaguars, the Chargers threw on three consecutive plays that began at or inside the 1, then tried a quarterback draw. They did not score, and time expired. The Rams had a fourth-and-goal from inches out against the Panthers and attempted a play-action pass. It fell incomplete, and when the Panthers took possession, they tried running the ball but got knocked backward, resulting in a safety. Kansas City's Jamaal Charles, third in the NFL in rushing, was thwarted by the Texans on a third-and-goal from inches away in the fourth quarter, and when the Chiefs tried a play-action pass on fourth down, it was incomplete.

A week earlier, the Ravens had first-and-goal at the 4 against the Packers, tried four runs by Ray Rice or Bernard Pierce, and turned the ball over on downs in a 19-17 loss. The Bills had first-and-goal at the 2 against the Bengals, and proceeded to run for 1 yard, run for no gain, run for no gain and get sacked on fourth down on the way to an overtime loss.

This is not to say zero teams can run. But they're rare and tend to create running room via zone-read options: Chip Kelly's Eagles when Michael Vick is healthy; the Seahawks with Russell Wilson; the 49ers with Colin Kaepernick. Those are the top three teams in yards rushing per game. The Redskins, led by Robert Griffin III, are second to Philadelphia in average gain.

"We like throwing the ball, too," Seattle coach Pete Carroll said, "but we really want to run the football."

Especially when it's time to extend a drive while trailing. Or run out the clock when ahead. Or bulling the ball in on fourth-and-goal from the 1.

"Teams that, week-in and week-out, do a good job of running the football still have a better chance of winning because it wears a defense out and it gives your defense a chance to rest. It's hard to do that with the passing game," Reeves said. "There's still a premium on running the football. Is it as much as it used to be? No, it's not."

___

AP Sports Writers Will Graves in Pittsburgh, Tim Booth in Seattle, Tom Canavan in New Jersey, Janie McCauley in San Francisco and AP Pro Football Writer Rob Maaddi in Philadelphia contributed to this report.

Copyright 2013 The Associated Press.